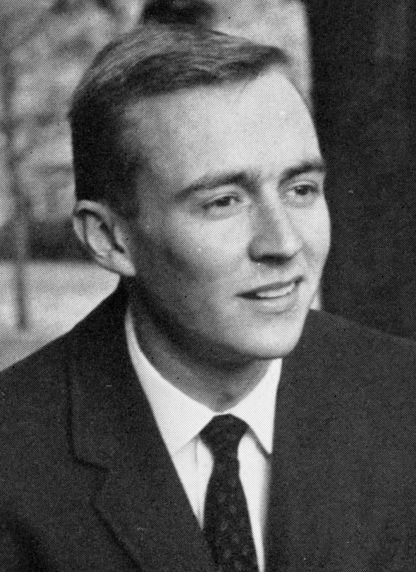

Elm Street — where nightmares undoubtedly occur — is located six blocks south of Wheaton College, but Wes Craven never lived in the last house on the left or anywhere else on that shaded lane. In fact, residing near the campus as a student, he rented rooms in  three different homes at various times on Scott, President and Franklin streets. The wildly successful film director, who died of brain cancer at 76 on August 30, 2015, studied English at Wheaton College from 1957-63. Raised in a strict Christian home in Cleveland, Ohio, his family was somewhat concerned that Wheaton College was “too liberal.” Inquisitive with a touch of the maverick, Craven was anxious to explore the power and passion of language, especially during the topsy-turvy 1960s. The March, 1962 Kodon, the Wheaton College literary magazine, sponsored a Creative Arts Festival with Pulitzer Prize-winning author Gwendolyn Brooks as one of the judges. Craven won first prize in the short story category. Serving as editor for the Fall, 1962 Kodon, he prophetically writes:

three different homes at various times on Scott, President and Franklin streets. The wildly successful film director, who died of brain cancer at 76 on August 30, 2015, studied English at Wheaton College from 1957-63. Raised in a strict Christian home in Cleveland, Ohio, his family was somewhat concerned that Wheaton College was “too liberal.” Inquisitive with a touch of the maverick, Craven was anxious to explore the power and passion of language, especially during the topsy-turvy 1960s. The March, 1962 Kodon, the Wheaton College literary magazine, sponsored a Creative Arts Festival with Pulitzer Prize-winning author Gwendolyn Brooks as one of the judges. Craven won first prize in the short story category. Serving as editor for the Fall, 1962 Kodon, he prophetically writes:

This edition of KODON will be controversial. It was not planned to be so, and were things ideal, it would not raise a whisper of protest. But the ideal is never here. So be it. Besides, a controversy is healthy, I feel, and constructive if carried on honestly and fairly. Let us hope that this will be the case in the consideration of this magazine’s contents….In addition, there is the conviction in this office that, in the arts, the Fundamental Christian world, and more specifically Wheaton, is sadly short of its potential and far behind its contemporaries. Therefore the copy of this magazine will remain (as long as the present staff remains), free and limited only by the criteria and the boundaries of artistry.

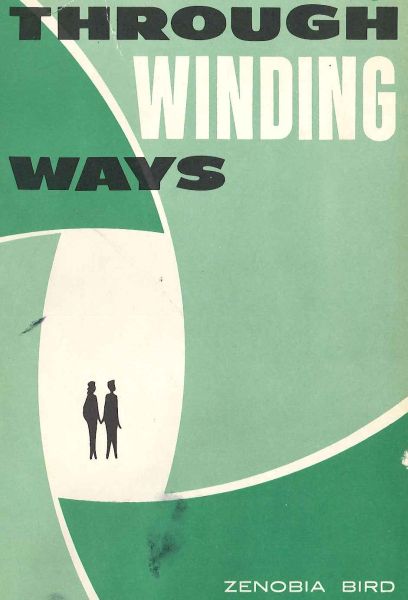

Braced for the fallout, Craven published two edgy-for-the-era stories, “A New Home,” by Marti Bihlmeier, about an unwed mother, and “The Other Side of the Wall” by Carolyn Burry, about an interracial couple. As predicted, the stories stirred discomfort in the campus community and were not well-received by the administration. Soon Dr. V. Raymond Edman, President of Wheaton College, informed Craven that he had failed in his duties as editor. Consequently, publication of Kodon was suspended for a year. Interestingly, this issue also features work by Jack Leax and Jeanne (Murray) Walker, who would enjoy successful careers as published poets and professors of literature.

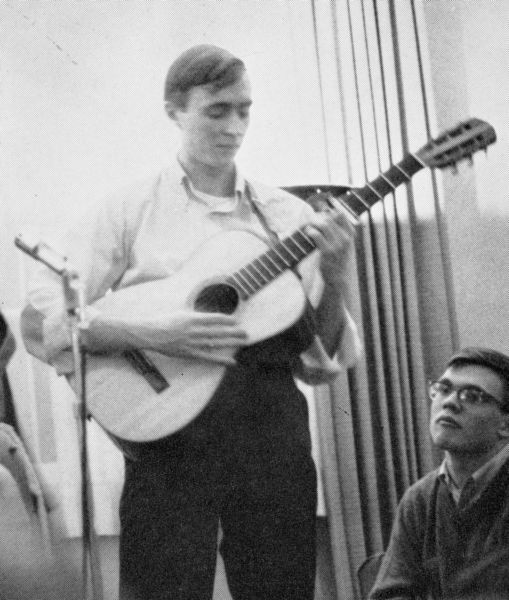

As a senior Craven was stricken with Guillan-Barre syndrome, paralyzed for several months from the chest down, delaying his graduation by nearly a year. During this difficult time he was visited by friends and several strangers. “I remember feeling terribly down,” Craven told a reporter in a June 8, 1997 Chicago Tribune interview. “People I didn’t know came to visit, to pray for my recovery.  To me, their thoughts and prayers represented the best side of Christianity. I’ll never forget that side of Wheaton College. Never.” A retired professor remembers Wes Craven as “a fine, serious-minded student” who excelled in Shakespeare and drama. In addition to deep, wide reading, Craven played guitar in a folk band.

To me, their thoughts and prayers represented the best side of Christianity. I’ll never forget that side of Wheaton College. Never.” A retired professor remembers Wes Craven as “a fine, serious-minded student” who excelled in Shakespeare and drama. In addition to deep, wide reading, Craven played guitar in a folk band.

Leaving Wheaton, he completed his graduate degree in philosophy and writing at Johns Hopkins. He briefly taught school in New York before committing his prodigious talents to Hollywood. Specializing in horror franchises, his directorial debut was The Last House on the Left (1972). Craven went on to write or direct A Nightmare on Elm Street (1984), The Serpent and the Rainbow (1988), Scream (1996) and the non-scary drama Music of the Heart (1999), starring Meryl Streep, who garnered an Academy Award nomination for her performance. He also published a novel, The Fountain Society (1999) and co-scripted a graphic-novel series called Coming of Rage (2014).