The following obituary for Miss Julia Blanchard and the accompanying eulogy from her funeral service, delivered by V.R. Edman, appear in the July/August, 1959, Wheaton Alumni magazine.

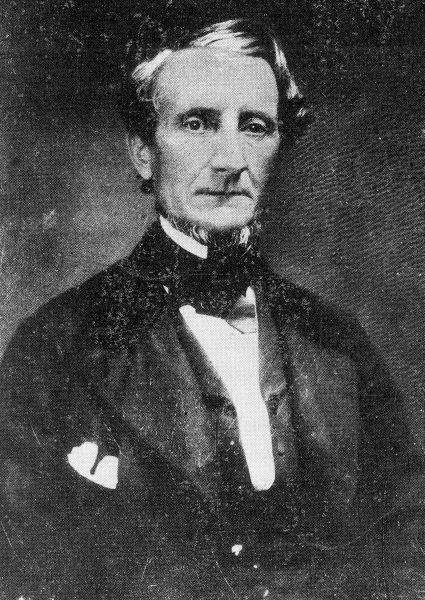

Serving actively in the Wheaton College Library, Miss Julia Blanchard started in 1908 as assistant librarian, and then in 1915 was named Librarian. At the time of her retirement in 1948 she was made a professor emeritus and granted the honorary degree “Doctor of Letters” and appointed the College Archivist. Most Wheaton alumni, with the possible exception of those in recent classes, knew “Miss Julia,” as she was affectionately called by her host of friends. Julia Eleanor Blanchard was born in Wheaton, August 7, 1878. She was the daughter of Dr. Charles Albert Blanchard and Margaret Ellen Milligan Blanchard, and one of the five children of that happy family. She was the granddaughter of Dr. Jonathan Blanchard, the first president of Wheaton and her father served for more than forty years as the second president of the College. Until a few months prior to her death, “Miss Julia” made the old Blanchard House at 623 Howard Street her residence. She died May 6, 1959, at the Geneva Community Hospital where she had been confined during the last months of her illness. The funeral service for Miss Julia was held in the College Church of Christ, of which she had been an active member for many years. Though not planned that way, the funeral service was most appropriate for a librarian who for so many years handled and loved books. From the hymnbook organist Reginald Gerig played and Elbert Dresser sang the favorite hymns of Miss Julia. Her pastor, Dr. L.P. McClenny, read from God’s book portions of Scripture that were the foundation of her faith as well as a source of comfort to all attending. Her former pastor, now College chaplain, Dr. Evan Welsh, spoke beautifully of “The Book of Remembrance” (Malachi 3:16), of them who “feared the Lord and spake often to one another.” President Dr. V. Raymond Edman then brought his message of comfort and hope on “The End of the Chapter.” In another tribute, Prexy had this to say, “To us who knew her these many years, Miss Julia herself was like a splendid book: clear type, bond paper and the best contents.”

Serving actively in the Wheaton College Library, Miss Julia Blanchard started in 1908 as assistant librarian, and then in 1915 was named Librarian. At the time of her retirement in 1948 she was made a professor emeritus and granted the honorary degree “Doctor of Letters” and appointed the College Archivist. Most Wheaton alumni, with the possible exception of those in recent classes, knew “Miss Julia,” as she was affectionately called by her host of friends. Julia Eleanor Blanchard was born in Wheaton, August 7, 1878. She was the daughter of Dr. Charles Albert Blanchard and Margaret Ellen Milligan Blanchard, and one of the five children of that happy family. She was the granddaughter of Dr. Jonathan Blanchard, the first president of Wheaton and her father served for more than forty years as the second president of the College. Until a few months prior to her death, “Miss Julia” made the old Blanchard House at 623 Howard Street her residence. She died May 6, 1959, at the Geneva Community Hospital where she had been confined during the last months of her illness. The funeral service for Miss Julia was held in the College Church of Christ, of which she had been an active member for many years. Though not planned that way, the funeral service was most appropriate for a librarian who for so many years handled and loved books. From the hymnbook organist Reginald Gerig played and Elbert Dresser sang the favorite hymns of Miss Julia. Her pastor, Dr. L.P. McClenny, read from God’s book portions of Scripture that were the foundation of her faith as well as a source of comfort to all attending. Her former pastor, now College chaplain, Dr. Evan Welsh, spoke beautifully of “The Book of Remembrance” (Malachi 3:16), of them who “feared the Lord and spake often to one another.” President Dr. V. Raymond Edman then brought his message of comfort and hope on “The End of the Chapter.” In another tribute, Prexy had this to say, “To us who knew her these many years, Miss Julia herself was like a splendid book: clear type, bond paper and the best contents.”

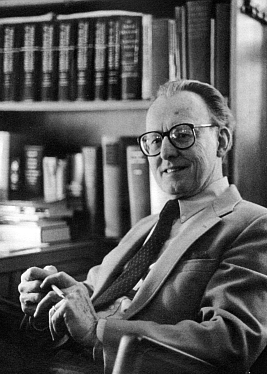

“The End of the Chapter” delivered by Dr. V. Raymond Edman

The conclusion of a chapter is not necessarily the ending of the book, unless it is the very best chapter. We have come to the first chapter in the history of the College with the homegoing of Julia Eleanor Blanchard. What a glorious chapter it has been, and how significant that it coincides with the dawning of our Centennial Year. The chapter began a hundred years ago in almost idyllic simplicity. Upon invitation from friends and from trustees of Illinois Institute, Jonathan Blanchard came to the little village of Wheaton on this wind-swept, relatively treeless prairie in 1859 to confer upon the founding of the College, which project was accomplished during the following year. This century-long chapter has been marked by struggles, by strength of character on the part of administration and faculty; and has been crowned with success. It has had its times of deep testing and tears but the outcome thereof has been triumph. There has been prayer with patience, faith with fortitude, consecration with courage, dedication in education with devotion to the Lord Jesus Christ. Like the tall elms and the broad maples that adorn its campus, the College has put its roots deep into the heart of God and spread its branches far afield in the earth. The chapter of this century that now closes is spanned by the Blanchards: Jonathan who founded the College and led it for twenty-two years; Charles Albert who carried it forward in days of difficulty or delight for another forty-four years; and concludes with the passing of Miss Julia who had been our librarian for nearly half a century. Miss Julia was always a great delight and encouragement to me. Again and again she told me of her grandfather and father, and when I would report to her an answer to prayer for the College or the provision of new buildings she would say, “Father would be thankful to know the continued blessings of the Lord among us here.” If she were here I would want to say to her again: “Miss Julia, the Book which your grandfather and your father believed to be the Word of the living God, we still believe! The Savior, the Lord Jesus Christ, whom they loved and served, we do still love and serve! The great essentials of the Christian faith as defined in our doctrinal platform we do believe wholeheartedly, and without any qualification or mental reservation! The vision of education that is thoroughly Christian which your grandfather and father had, we have, and will continue to make a reality to our children!”

The chapter of Wheaton’s first century closes, and a new one begins. It is our responsibility to read well what has been written in that chapter so that the one we write today and tomorrow, as our Lord tarries, will conform to what which we have learned from our Fathers. The Blanchards have written clearly and cogently, and at the passing of Miss Julia we reaffirm our faithfulness to the trust committed to us. So help us God!