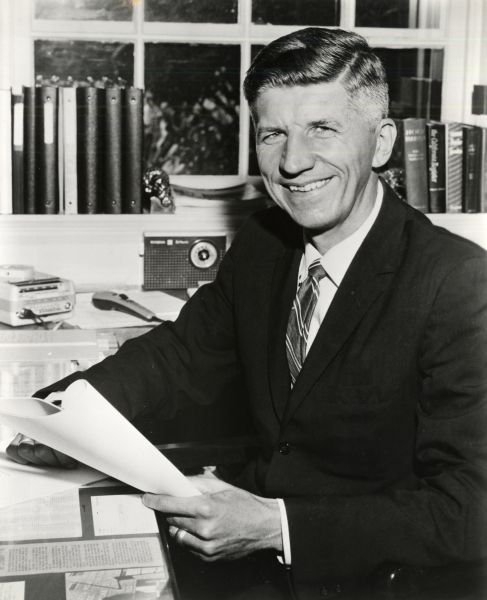

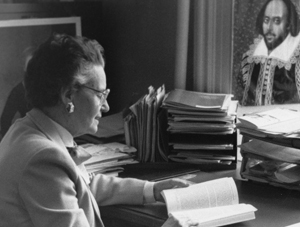

Twenty years ago, the Wheaton Alumni magazine began a series of articles in which Wheaton faculty told about their thinking, their research, or their favorite books and people. Professor of Conducting Mary Hopper was featured in the Spring 1993 issue.

As I was driving to the College one day last fall, I tuned in to the public radio station. A discussion of women’s issues was in progress, and I found myself in total agreement with the speaker as she described the strides and setbacks women have made in the professional world.

As I was driving to the College one day last fall, I tuned in to the public radio station. A discussion of women’s issues was in progress, and I found myself in total agreement with the speaker as she described the strides and setbacks women have made in the professional world.

Then she made a statement to the effect that the entire future of women’s rights hinged on the abortion issue, If anyone was watching me as I drove along Harrison Street, they would have been amazed to see me, first nodding in agreement, and then, suddenly, furiously shaking my head.

During the political campaign last year, I became quite distressed over the discussions that polarized the right-wing expression of “family values” and the left-wing advocacy of pro-choice. This reasoning appeared to provide only two alternatives for women: either to choose a traditional, early twentieth century female role, or to become “pro-choice/liberal” career women.

Where does this leave single women, single-parent families, couples unable to have children, and women who honestly seek to develop the gifts that God has bestowed upon them in addition to those of being wives and mothers? How many women in our country work because they have to support a family? How is a woman to function in her family?

There are many questions about the role of women in society. As a working mother myself, I struggle with such issues every day. It is not surprising that many Christian women today wonder with uncertainty about their future.

Two years ago, I taught a student who decided to leave Wheaton because her goal in life was to be a housewife and mother, and she didn’t want to work as hard to get her college degree as she would have to work at Wheaton. She was a very bright and gifted young musician with great potential for teaching. Her mind was made up, but in counseling with her, I shared my perceptions about her decision. I told her about some of my friends’ marriages, which were unhappy or had ended in divorce because both partners were not devoted to the full development of their talents. Having been single myself for quite a few years, I pointed out to her that not everyone is destined for marriage. I challenged her not to throw away her gifts merely because she was waiting for the right relationship to come along.

At Wheaton, many women are role models for our young women–they may he single; married, with or without families; at different stages of their lives; and working in almost any area of the College. I have come to realize that part of my calling to teach at Wheaton is to try to live as a woman devoted to serving Christ through her profession, her marriage, and her family.

Another part of my role as a professor is to help my students recognize and develop their gifts. In the parable of the talents, Jesus exhorts us all to develop the gifts that have been given to us, not to bury them. Many of our young women are surprised to learn that they have anything to contribute. Some live with such insecurity that it is a major revelation to them to think that they can he competent conductors, or teach music lessons, or acquire the self-confidence to perform.

I rejoice when I think of women I have taught working in the business world, in education, on the mission field, in graduate school, and in their homes. I am thankful for the small part I have been able to play in their development during the years they spent at Wheaton College.

My prayer is that Wheaton will continue to provide role models of many kinds for our students, whether those role models are trustees, faculty, staff, or administrators. It should he apparent to our students that we are all concerned about our personal lives as well as our professional lives. And it should be clear to our students that we care about them, as we push them to achieve the most they can during their years at Wheaton.

Ultimately, the measure of our success as educators and as mentors is the degree to which they learn to serve the Lord with their whole being in the exercise of their talents and skills, as well as in their attention to their roles as men and women.

———-

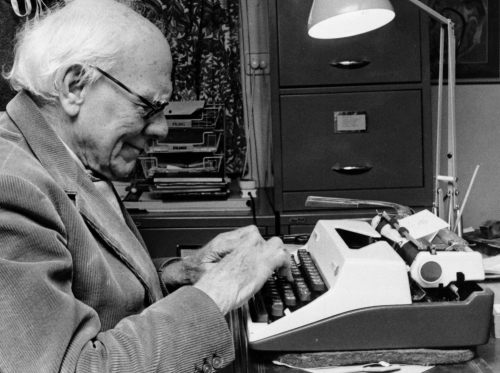

Mary Hopper is Professor of Choral Music and Conducting at the Wheaton College Conservatory of Music. She also conducts both the Men’s Glee Club and the Women’s Chorale and has toured nationally and internationally with both ensembles to great success. She holds degrees from Wheaton College and the University of Iowa, where she studied with Don V. Moses. Before coming to Wheaton, Dr. Hopper taught public school music in the Chicago area, and choral conducting and voice at the University of Minnesota (Morris). Her ensembles frequently appear at conventions of the ACDA, most recently, the Women’s Chorale at the National Convention in New York City, February 2003. The Men’s Glee Club will appear at the Illinois ACDA Convention in October, 2008. Dr. Hopper is in demand nationally as a guest conductor and clinician. During the 2007-08 academic year she conducted the Illinois and Louisiana All-State Choirs. She has served ACDA as Illinois State President and is presently ACDA Central Division President-Elect. In October 2010 she received the Distinguished Service to Alma Mater Award at Homecoming.