Wheaton faculty Steve Moshier, David Maas and Jeff Greenberg recently saw the publication of their article on the history of geology at Wheaton College and its engagement with Wheaton’s theological stance and teachings in Geology and Religion: a history of harmony and hostility (Geological Society, London).

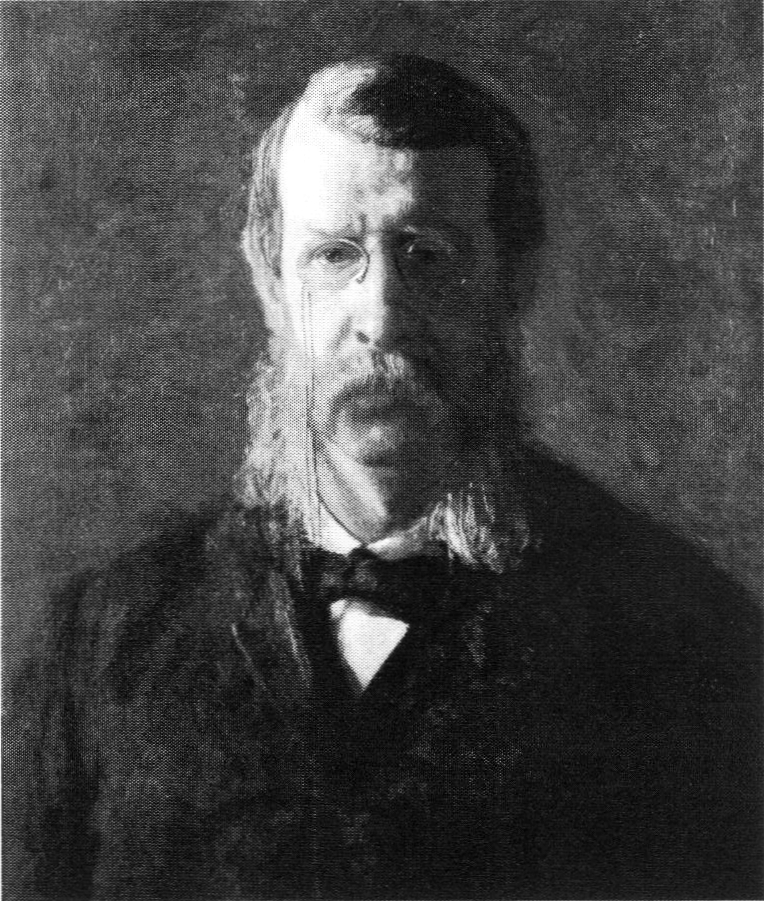

Since the college’s founding in 1860, geology has been part of its curriculum. Jonathan Blanchard sought to recruit the best faculty possible and this was true for the natural sciences as it was for the humanities. One of his first recruits was George Frederick Barker, whom Blanchard wanted to teach geology and natural history. Unfortunately, due to a number of circumstances his appointment lasted one year.

As scientific knowledge grew the tensions between science and religion began to grow. These emerged, in some campes, shortly after Darwin’s writings became widely available and taught. Wheaton’s geology faculty respected the geological evidence for an ancient Earth and interpreted Genesis’ telling of creation and its chronology as representing epochs of God’s creative activity. Wheaton’s first faculty member with an earned doctorate was L. Allen Higley,  who harmonized mainstream geological history and the Bible through the gap or ruin-restoration interpretation, wherein the epochs of geological time preceded the biblical account of six days of recreation several thousand years ago. Higley and his ideas became a major influence in Wheaton’s interactions with its fundamentalist constituents and its recruiting of new faculty. By the 1930s geology became an established major and an independent department in 1958. Like the study of human origins, geology education at Wheaton has been profoundly influenced by the tension between science and faith in the evangelical sub-culture, causing concern in certain quarters. Wheaton’s faculty and administration have had to address these concerns on numerous occassions since the 1960s.

who harmonized mainstream geological history and the Bible through the gap or ruin-restoration interpretation, wherein the epochs of geological time preceded the biblical account of six days of recreation several thousand years ago. Higley and his ideas became a major influence in Wheaton’s interactions with its fundamentalist constituents and its recruiting of new faculty. By the 1930s geology became an established major and an independent department in 1958. Like the study of human origins, geology education at Wheaton has been profoundly influenced by the tension between science and faith in the evangelical sub-culture, causing concern in certain quarters. Wheaton’s faculty and administration have had to address these concerns on numerous occassions since the 1960s.