Chicago and its suburbs host an array of influential “megachurch” campuses, each comprising congregations of several thousand members. Willow Creek, Harvest Bible Chapel, Christ Community and others, attempting to attract unbelieving seekers and disenfranchised Christians, typically eschew in their services the elements of “old-fashioned” worship such as hymns, pews and traditional architecture, instead using praise bands, humorous skits and theater-style seating. A lesser-known megachurch, at least among Evangelicals, is First Baptist Church of Hammond, Indiana, located in the northwest corner of the state. Contrary to megachurch methodology, First Baptist doggedly maintains an adherence to revivalistic evangelism, the singing of gospel songs and an unwavering insistence on the King James Bible as superior to all successive translations.

Chicago and its suburbs host an array of influential “megachurch” campuses, each comprising congregations of several thousand members. Willow Creek, Harvest Bible Chapel, Christ Community and others, attempting to attract unbelieving seekers and disenfranchised Christians, typically eschew in their services the elements of “old-fashioned” worship such as hymns, pews and traditional architecture, instead using praise bands, humorous skits and theater-style seating. A lesser-known megachurch, at least among Evangelicals, is First Baptist Church of Hammond, Indiana, located in the northwest corner of the state. Contrary to megachurch methodology, First Baptist doggedly maintains an adherence to revivalistic evangelism, the singing of gospel songs and an unwavering insistence on the King James Bible as superior to all successive translations.

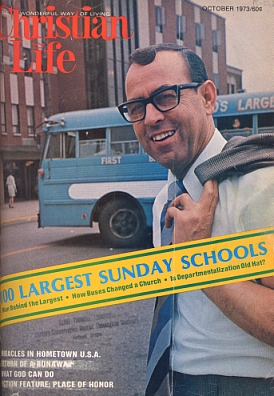

Founded in 1887 by Allen Hill, First Baptist grew steadily under a series of dedicated pastors, each contributing a unique strength. Notable among them was Dr. J.M. Horton, who served for fourteen years until resigning to lead the Indiana Baptist Convention. After Horton came Dr. T. Leonard Lewis, graduate of Wheaton College and Moody Bible Institute, who served for three years until resigning to assume the presidency of Gordon College in Boston. Then in 1944 came Dr. Russell Purdy, recommended to First Baptist by Dr. Will Houghton, president of Moody Bible Institute, and Dr. Harry Ironside, pastor of Moody Memorial Church. Purdy’s 1947 departure opened the way for Dr. Owen Miller, a supporter of missions and church plants. Miller served faithfully until 1958, leaving for Riverside, California; and again First Baptist sought a pastor. Several candidates interviewed with the trustees and deacons, but the most intriguing was a young Texas firebrand named Jack Hyles. As Keith McKinney and Gail Merhalski remark in The Old Church Downtown (2001),  “Pastor Hyles’s preaching was different…Most of the guest preachers were serious, staid and stiff in their delivery…The most interesting pulpit supply were faculty members from Wheaton College…to put it mildly, most could not be heard above the occasional cough…Brother Hyles, on the other hand, preached!” Not surprisingly, Hyles was elected. In addition to breathing vigor into First Baptist’s evangelistic efforts, he promptly severed its ties from both Southern and American Baptist conventions, sensing an alarming drift toward ecumenism. Under his leadership First Baptist’s various outreaches dramatically expanded; and in 1973 Christian Life magazine recognized it as conducting one of the “100 Largest Sunday Schools.” With multimillionaire contractor Russell Anderson, Hyles co-founded Hyles-Anderson College in Schererville, Indiana, in 1972.

“Pastor Hyles’s preaching was different…Most of the guest preachers were serious, staid and stiff in their delivery…The most interesting pulpit supply were faculty members from Wheaton College…to put it mildly, most could not be heard above the occasional cough…Brother Hyles, on the other hand, preached!” Not surprisingly, Hyles was elected. In addition to breathing vigor into First Baptist’s evangelistic efforts, he promptly severed its ties from both Southern and American Baptist conventions, sensing an alarming drift toward ecumenism. Under his leadership First Baptist’s various outreaches dramatically expanded; and in 1973 Christian Life magazine recognized it as conducting one of the “100 Largest Sunday Schools.” With multimillionaire contractor Russell Anderson, Hyles co-founded Hyles-Anderson College in Schererville, Indiana, in 1972.

Ministering widely within Fundamentalist circles, he enjoyed a tight friendship with Dr. John R. Rice, founder and editor of The Sword of the Lord, located in Wheaton, Illinois. In 1960 Rice asked Hyles, who had been serving as assistant editor of the newspaper, to assume the editorship, providing that he resign and move to Wheaton. Hyles, reluctant to surrender his pulpit, declined and resumed his position on the Sword’s board of directors, while Rice in 1963 moved all operations to Murfreesboro, Tennessee.

Ministering widely within Fundamentalist circles, he enjoyed a tight friendship with Dr. John R. Rice, founder and editor of The Sword of the Lord, located in Wheaton, Illinois. In 1960 Rice asked Hyles, who had been serving as assistant editor of the newspaper, to assume the editorship, providing that he resign and move to Wheaton. Hyles, reluctant to surrender his pulpit, declined and resumed his position on the Sword’s board of directors, while Rice in 1963 moved all operations to Murfreesboro, Tennessee.

During the late 1960s Hyles spoke at Moody Founder’s Week in Chicago, Illinois, Rex Humbard’s Cathedral of Tomorrow in Akron, Ohio, and Oswald J. Smith’s People’s Temple in Toronto, Ontario. But as the years progressed, he limited his engagements, cautious of theological compromise.

In this sphere he squarely placed Wheaton College, about which he infrequently but always pointedly referenced in his preaching, as in this 1975 sermon, favorably invoking an older era to illustrate God’s restorative power:

“Right over here in Wheaton, Illinois, the President of Wheaton College, Dr. [Charles] Blanchard, told how a man had died and they had covered him up. His wife got under the sheet that was over his body. She stayed there and said, ‘He’s not going to die!’…He got up and the wife started walking out the door with him. A dead man! The doctor said, ‘Hey, you can’t walk out the door. You’re sick.’ The wife said, ‘No, he’s not sick. He’s dead. Leave us alone!’ They went home. Yes, God can still do it!”

More often, however, Hyles cited Wheaton College as a plum example of how not to administrate a Christian school, as in this 1970 sermon:

“Here is the problem, and here is what is causing these little, immature, teenage pink punks to ruin our country (and they’re letting them do it). The reason they are is because we older people are letting them do it…Let’s take an example – and I’ll just come right out and say it – let’s take over here in Wheaton College. It used to be a wonderful center for the Truth. There was a day when Wheaton College was one of the grandest and greatest colleges in America. No longer is that true…Wheaton College was in our budget when I came eleven years ago to pastor this church. As long as I’m here, it’ll never get in our budget again. Never. You say, ‘I don’t like that!’ Well, you can lump it the best way you can, because I don’t like it either. I am sick and tired of Christian colleges hiding behind last generation’s character, kowtowing to a generation of beatniks and liberals, and acting like them. Listen, if Wheaton College were what it ought to be tonight, let them take a stand on the issues of our day; let them fight and get bloody for the Bible again like they used to.”

He expresses a similar conviction in Fundamentalism in My Lifetime (2002):

“Basically, Bob Jones University was ‘The Wheaton College of the South.’ However, because Wheaton College was much older than Bob Jones University, it changed sooner. Bob Jones University remained fundamental, as nondenominationalists go, later than Wheaton College, because of its age.”

After Dr. Jack Hyles’s death in 2001, his son-in-law, Dr. Jack Schaap, was elected senior pastor. Each week First Baptist Church continues to operate a fleet of buses throughout Chicagoland and northwest Indiana. Matthew Barnett, pastor of Angelus Temple, founded by Aimee Semple McPherson in 1920, cites First Baptist as a model for urban ministry.