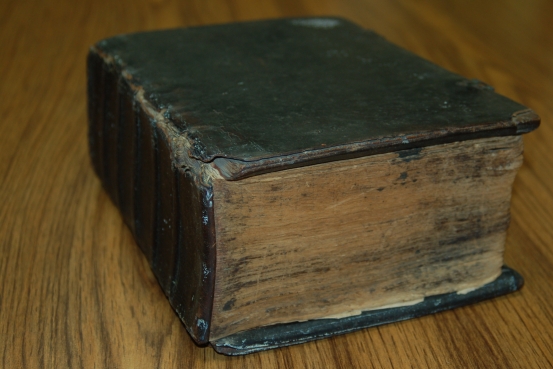

One would think that Wheaton College would have one of the best bible collections around–at least among small colleges. Unfortunately, this is not the case. However, over time and through purchasing and gifts it is possible for Wheaton expand its current holdings. One way in which the Archives & Special Collections has expanded its holding is through the acquisition of several collections that had been a part of the holdings of the Billy Graham Center Museum and Library. One such gem that came via the museum was a copy the first bible printed in America in an European language (German). A later edition of this bible became known as the “gun-wad bible” because during the Battle of Germantown (1777) during the American Revolution British soldiers broke into the printer’s shop and confiscated thousands of pages of the yet completed bibles and used them for gun-wadding.

Christopher Sauer, born Johann Christoph Sauer in 1695, sailed to America with his wife and young son in 1724 and nearly fifteen years later had established a thriving printing business. Historians have recognized Christopher Sauer (also known to history as Johann Christoph Sauer, Christoph Saur, Christoph Sauer and Christopher Sower) as one of the most important figures of colonial Pennsylvania. Sauer was known as a separatist and did not seem to be a part of any particular religious community, though his wife had moved to the Ephrata commune near Germantown, leaving the senior and junior Christoph.

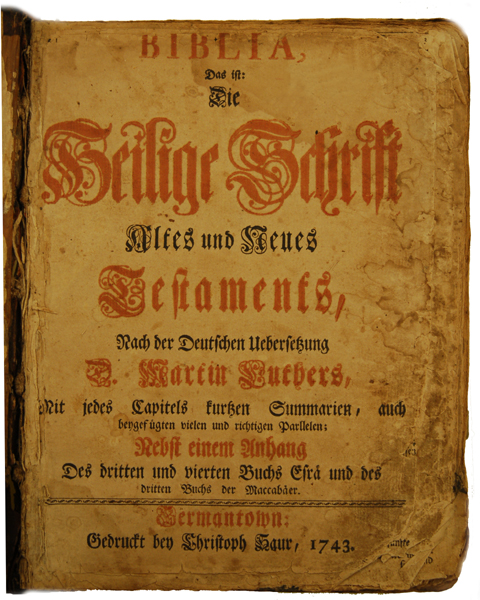

In 1743 Saur printed the first European-language Bible printed in America. The only bible printed in America prior to this was John Eliot’s Algonquin Bible (1663). Sauer’s bible was a huge undertaking and became a 1267 page volume. This is considered one of the largest printing ventures in America at the time. Eventually the 1200 copies printed were sold. Though he was a business man he made it known that those who were poor and could not afford his bible could ask to receive one. Sauer’s son eventually printed a second edition in 1763 and a third in 1776 (mentioned above) — all before Robert Aitken’s “Congress Bible” of 1782.

As would reflect the future nature of American religion, Sauer’s bible created controversy and division even before it was finished. Area Lutheran and Reformed clergy feared the translation chosen, Berleberg’s, along with some of the printing’s typographical errors would confusion readers and encourage heresy. Sauer did not help his situation by using multiple translations in a single book (Job). Despite the pressure Sauer pressed on.

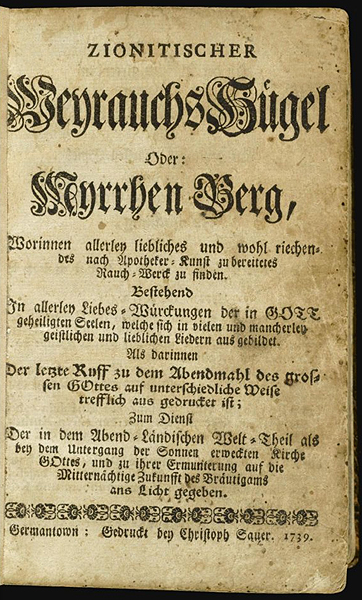

To date about two hundred of Sauer’s publications have been identified. His press, which he built himself, was quite active and produced a steady stream of devotional and theological works. Some of the earliest hymnals for German speakers came from Sauer’s press. In fact the first publication off of his press was a hymnal that was reprinted over and over again. The type was sent to him from Germany by Christopher Shutz. Sauer was well-acquainted with revivalist George Whitefield and had hopes of printing devotional and theological works in English, including a quarto-sized bible, but the high cost of paper proved a hurdle too great.

To date about two hundred of Sauer’s publications have been identified. His press, which he built himself, was quite active and produced a steady stream of devotional and theological works. Some of the earliest hymnals for German speakers came from Sauer’s press. In fact the first publication off of his press was a hymnal that was reprinted over and over again. The type was sent to him from Germany by Christopher Shutz. Sauer was well-acquainted with revivalist George Whitefield and had hopes of printing devotional and theological works in English, including a quarto-sized bible, but the high cost of paper proved a hurdle too great.

His motto for his press was “For the glory of God and my neighbor’s good.” Sauer wrote to a patron in September, 1740, that “I would rather serve my neighbor and glorify God in that way than to gather a large earthly fortune for myself or for my son….” He continued, saying, “that nothing shall be printed except that which is to the glory of God and for the physical or eternal good of my neighbors. What ever does not meet this standard, I will not print. I have already rejected several, and would rather have the press standing idle. I am happier when I can distribute something of value among the people for a small price, than if I had a large profit without a good conscience.” He was known for his charitable works, so much so that he was known as “Bread Father” and the “Good Samaritan” of Germantown. It is said that he would meet German immigrants as they arrived on ships provide hospitality to the sick and needy.

Sauer did what he could to expand his work and to make his publications affordable. He had heard of a printer in Philadelphia that claimed knowing the formula for a better ink and Sauer inquired about learning the formula. Asking what the printer would ask in return for teaching Sauer the printer asked Sauer to build him a press like his own. Saying he would consider the trade Sauer later thought to myself, “You have carried on twenty-six trades and crafts without any teacher, and made almost all of the tools necessary for them. Why should you now pay so dearly for this knowledge?” The next morning he had an idea on how to make the a new ink. The ink was as good and even cheaper than the old.

Sauer did what he could to expand his work and to make his publications affordable. He had heard of a printer in Philadelphia that claimed knowing the formula for a better ink and Sauer inquired about learning the formula. Asking what the printer would ask in return for teaching Sauer the printer asked Sauer to build him a press like his own. Saying he would consider the trade Sauer later thought to myself, “You have carried on twenty-six trades and crafts without any teacher, and made almost all of the tools necessary for them. Why should you now pay so dearly for this knowledge?” The next morning he had an idea on how to make the a new ink. The ink was as good and even cheaper than the old.

Christopher Sauer died on September 25, 1758, after a remarkable career in America. During his thirty-four years in America his press operation and intellectual interests put him at the forefront of many of the important controversial political and theological issues of his day. About one fifth of the publications of his press were translations or reprints of European books, largely theological or devotional in nature. These productions helped to maintain America’s European ties. Conversely, many of Sauer’s American works were reprinted in Europe, bringing ideas from the New World to the Old.

This entry in indebted to Donald Durnbaugh’s wonderful article on Sauer.

[Durnbaugh, Donald F. “Christopher Sauer Pennsylvania-German Printer: His Youth in Germany and Later Relationships with Europe.” The Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography, Vol. 82, No. 3 (Jul., 1958), pp. 316-340.]