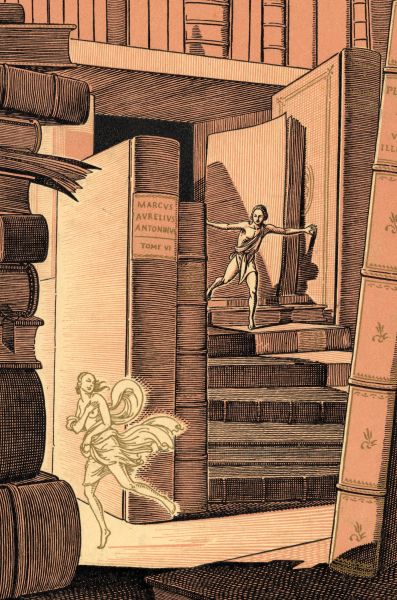

For various reasons books occasionally do not make it into a reader’s hands; and so the book that might-have-been acquires a sort of mystique. “A lost book,” writes Stuart Kelly in The Book of Lost Books: An Incomplete History of All the Great Books You’ll Never Read (2005), “is susceptible to a degree of wish fulfillment. The lost book, like the person you never dared asked to the dance, becomes infinitely more alluring simply because it can be perfect only in the imagination.” The simplest form of loss, notes Kelly, is destruction. An infamous example is the legendary Library of Alexandria, supposedly holding all the wisdom of the ancient world, burning to ashes in a single night. Other books are sacrificed to carelessness, as when a certain publisher moved offices, absentmindedly leaving behind manuscripts in a building slated for immediate demolition. Some books never achieve completion because of the death of the author, as when Charles Dickens expired before solving The Mystery of Edwin Drood, or Geoffrey Chaucer reached his eternal destination before his storytelling pilgrims reached their earthly destination in The Canterbury Tales. Often writers simply lose interest in a project. Probably every archive holding printed matter contains unpublished manuscripts.

For various reasons books occasionally do not make it into a reader’s hands; and so the book that might-have-been acquires a sort of mystique. “A lost book,” writes Stuart Kelly in The Book of Lost Books: An Incomplete History of All the Great Books You’ll Never Read (2005), “is susceptible to a degree of wish fulfillment. The lost book, like the person you never dared asked to the dance, becomes infinitely more alluring simply because it can be perfect only in the imagination.” The simplest form of loss, notes Kelly, is destruction. An infamous example is the legendary Library of Alexandria, supposedly holding all the wisdom of the ancient world, burning to ashes in a single night. Other books are sacrificed to carelessness, as when a certain publisher moved offices, absentmindedly leaving behind manuscripts in a building slated for immediate demolition. Some books never achieve completion because of the death of the author, as when Charles Dickens expired before solving The Mystery of Edwin Drood, or Geoffrey Chaucer reached his eternal destination before his storytelling pilgrims reached their earthly destination in The Canterbury Tales. Often writers simply lose interest in a project. Probably every archive holding printed matter contains unpublished manuscripts.

The Wheaton College Archives & Special Collections houses a few such documents, material undoubtedly meant to be edited, packaged and distributed to the public, but is now foldered neatly in acid-free boxes and shelved in a climate-controlled facility. A brief survey follows:

The second president of Wheaton College, Dr. Charles Blanchard, left for posterity Psychological Foundations, a book-length manuscript discovered as a worn, yellowed roll in the Blanchard home in 1949 by Dr. Clyde Kilby and Miss Julia Blanchard. It advances Blanchard’s observations regarding the development of the “soul life.”

The late Dr. Joe McClatchey (SC-45), professor of English at Wheaton College, wrote The Praise of God in Literature: From Homer to Hopkins, a 400-page study of worship in western literature as seen throughout the centuries.

Jeanne Murray Walker (SC-72), poet, playwright and Professor of English at the University of Delaware, penned a young adult novel entitled Stranger, dated 1989. Though her editors were favorable and encouraged revision, the book was not published.

Academic Arthur Christy (SC-82), recipient of the Guggenheim Fellowship for Intellectual History and American Literature, committed several years to researching The Thoreau Fact Book, reflecting his interest in the New England transcendentalists. It remained unfinished upon his death in 1946.

The brilliant missionary and political professor, Dr. Kenneth Landon (SC-38), husband of Margaret Landon, author of Anna and the King of Siam, composed an unpublished history of Malaya, along with several uncollected short stories, some of which initially appeared in the Saturday Evening Post.

And, among the papers of Madeleine L’Engle (SC-03), author of A Wrinkle in Time, lay several unpublished manuscripts, including sermons, short stories, retreat addresses, a handwritten novel called The Feast of Stephen and a nearly completed novel called A Lost Innocent, featuring Camilla, who first appeared in Camilla Dickinson (1951) and later in A Live Coal in the Sea (1996). Also archived is the text for an illustrated children’s book titled Moses, Prince of Egypt, intended for release with the 1998 DreamWorks animated film.

Though “lost” to the general public, these works are fortunately still available for inspection in Wheaton’s Manuscript Reading Room.