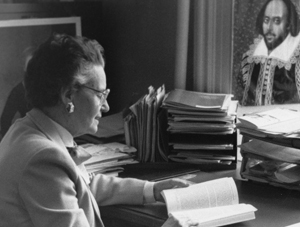

Twenty years ago, the Wheaton Alumni magazine began a series of articles in which Wheaton faculty told about their thinking, their research, or their favorite books and people. Professor of English Emeritus E. Beatrice Batson (who taught at Wheaton from 1957-1987) was featured in the August/September 1991 issue.

When I came to teach at Wheaton in the autumn of 1957, I discovered a nucleus of professors and students charged with excitement over Wheaton’s mission as a Christian liberal arts college. Combined with this concern was the belief that mind and spirit should he so constantly and consistently nurtured that complacency would be highly unlikely to make permanent inroads. I found the atmosphere extraordinarily exhilarating. Admittedly, some of us were idealists; perhaps such idealists that not a few individuals determined to find new and different ways of talking about the whole educational process. Through the decades, however, there were still those who were unable to think dispassionately of Wheaton’s mission. Similar zeal is by no means absent in 1991.

When I came to teach at Wheaton in the autumn of 1957, I discovered a nucleus of professors and students charged with excitement over Wheaton’s mission as a Christian liberal arts college. Combined with this concern was the belief that mind and spirit should he so constantly and consistently nurtured that complacency would be highly unlikely to make permanent inroads. I found the atmosphere extraordinarily exhilarating. Admittedly, some of us were idealists; perhaps such idealists that not a few individuals determined to find new and different ways of talking about the whole educational process. Through the decades, however, there were still those who were unable to think dispassionately of Wheaton’s mission. Similar zeal is by no means absent in 1991.

Several years following that autumn of 1957, I met at a professional conference one of my former students, then an advanced graduate student at Yale. Among the first questions he asked me were: ‘What are Wheaton students really like now?” and “Is the faculty remembering the mission of the College?” Or in paraphrase, “Are faculty members consciously aware that they are teaching human beings who must make moral and spiritual responses in life ?”

My reply to him was another question: “What kind of student do you wish to see at Wheaton?” Quick as a flash, he answered, “Hungry students. Let them he cynical, and let them be angry.” He continued, “But whatever they are, be sure they are hungry–hungry for nourishment that feeds mind, heart, and spirit.” What came clear was that somebody had a heavy and joyous responsibility. “To study at a college like Wheaton,” he insisted, “is to he exposed to a faculty and a curriculum that will not let students forget the large human questions of meaning and purpose.” However excellent the speakers at that professional conference may have been, it was the urgent tone of my former student’s pleas that lingered longest in my memory.

With the onslaught of unparalleled campus unrest in many colleges and universities during the late sixties and early seventies, prophets of doom began to declare that the liberal arts ideal would wither away or bit by bit literally slip from consideration in the strongest liberal arts colleges. Problems were far too complex, we were frequently told, for contemporary students to spend time on “the arcane vestiges of the past,” as critics pejoratively titled the liberal arts. To jettison every thinker and artist prior to the late twentieth century seemed no solution to some of us. Minds and imaginations burnished on Plato and Aristotle, Aeschylus and Shakespeare, Augustine and Kierkegaard (and scores of others) might well be the sort of informal minds and lively imaginations that should be working on different issues, we reasoned. Besides, students hungered for meaning and purpose.

What my former student urged still persisted in my mind in more recent years when numerous educational leaders held that students were in college to acquire a passport to immediate pleasure, instant success, and economic affluence. This indictment, however, failed to dissuade some of us from our firm belief in the mission of a Christian liberal arts college.

When I left close contact with the thinking of students and faculty for retirement in 1988, I continued to teach one course in Shakespeare. Although I was aware of new theories that pervaded scholarly writing and knew of the abuse that pseudo-scholars heaped upon those who affirmed the liberal arts ideal, I continued to discover that students did not consider Shakespeare’s works to be anachronisms. They perceived that his inimitable writings embodied large human questions and always-contemporary subjects even though the great artist wrote 400 years before they were horn.

In October 1990, I came from active retirement to serve as Kilby Professor of English and from October to May as acting chair, due to the serious illness of my colleague, Dr. Joe McClatchey. In these responsibilities, I had a closer contact with students and more interaction with faculty.

Since that autumn in 1957, many changes have occurred. In this year, 1990-91, faculty were challenging luminaries on their own ground, discussing terms not even named in 1957; students were wrestling with new issues, thinking hard on complexities born of their technological age. As before, there was still a nucleus who saw themselves as “privileged inheritors of a rich legacy” the mission of the Christian liberal arts college. I have a deep conviction, even in my most pessimistic moments, that Wheaton has in its community particular individuals who know that they are “custodians of something immensely valuable,” and they sense a dire need to keep it alive.

———-

Dr. E. Beatrice Batson, Professor Emerita of English, was chair of the department for 13 years. During the academic year 1990-91, she served as Kilby Professor of English and as acting chair. Since her retirement she continues her work as coordinator of the Shakespeare Collection and has organized bi-annual institutes for undergraduate teachers of Shakespeare, sponsored by the Shakespeare Special Collection, since 1992. She received the Wheaton College Alumni Association Distinguished Service to Alma Mater Award in 2007.