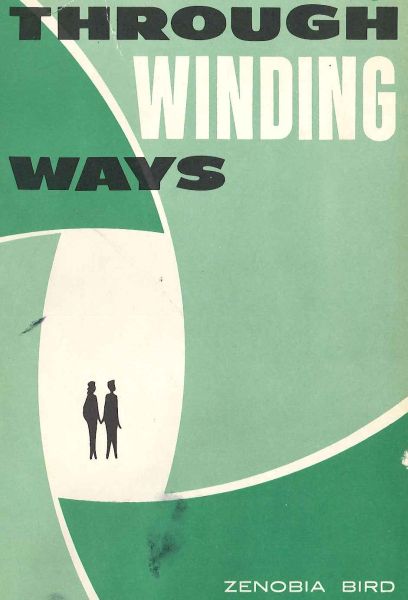

The following text, describing Wheaton College founder, Jonathan Blanchard, and his son, Charles, is excerpted from the prologue to Through Winding Ways (1939) by Zenobia Bird (Laura LeFevre). This is one of at least three novels, including The Tower, The Mask and the Grave (2000) by Betty Smartt Carter and The Silver Trumpet (1930) by John Wesley Inglis, featuring Wheaton College as its setting.

The following text, describing Wheaton College founder, Jonathan Blanchard, and his son, Charles, is excerpted from the prologue to Through Winding Ways (1939) by Zenobia Bird (Laura LeFevre). This is one of at least three novels, including The Tower, The Mask and the Grave (2000) by Betty Smartt Carter and The Silver Trumpet (1930) by John Wesley Inglis, featuring Wheaton College as its setting.

A man stood looking at a lone college building, small, plain, but sturdily built — his citadel, and then he turned and gazed long and far into the distant future. The wide prairie, flat and treeless, stretched out before him. That huddle of houses was the nearby village, while here and there an occasional farmhouse with young orchard and freshly planted shade trees gladdened the view and broke the monotony of the miles.

He was not given to dreaming, this pioneer from rock-ribbed Vermont, but a mighty vision gripped his soul. He was a born educator and an evangelist. The low hill upon which he stood was consecrated ground, dedicated in prayer to the cause of Christian education. Others had chosen the spot and launched the venture, but God had called him to captain the enterprise and lead on to vaster endeavor. As he looked with kindling eyes down the vista of the years, in vision he saw them, a troop of young men and women trained in the college that was to be, and going out as laborers in the Master’s vineyard to win souls for Christ and His Kingdom.

A quarter of a century rolled by, and in his place stood another Valiant-for-Truth, his son. Part of the dream of father and son has been fulfilled. On the hill now rose a stately white stone edifice of noble proportions, not supplanting, but surrounding and embodying in itself that which first had been. In the forefront of the building a Norman tower of simple beauty and dignity overlooked all the landscape. The bell in the turret was cast for its own noble purpose and bore in Latin the motto of the college, “For Christ and His Kingdom.”

This man for long years labored indefatigably to build a great college that would honor and glorify the Savior of the world (by rhonda). With painstaking care he laid the foundation solidly on the Rock, Christ Jesus himself the chief cornerstone. Into the spiritual structure, as real to the builder as the college walls of cut stone, there was built with purpose sure the sincere teaching of the Word of God.