God’s Economy: Faith-Based Initiatives and the Caring State, a recent University of Chicago Press publication by Lew Daly brings to the fore the intellectual history of the faith-based initiative. Digging through the Daniel Coats Papers, Daly, a senior fellow at Demos, a nonpartisan public policy research and advocacy organization, traces the roots of the faith-based initiative to the pluralist tradition of Europe’s Christian democracies, in which the state shares sovereignty with social institutions. Daly argues that Catholic and Dutch Calvinist ideas played a crucial role in the evolution of this tradition, as churches across nineteenth-century Europe developed philosophical and legal defenses to protect their education and social programs against ascendant governments. Daly untangles the radical beginnings of the faith-based initiative and the influence of this heritage on the past three decades of American social policy and church-state law. Daly also makes an effort to free the concepts from the narrow culture-war framework that has limited debate on the subject since Bush opened the White House Office for Faith-Based and Community Initiatives in 2001 and as President Obama signals a sharp break from many Bush Administration policies. Like Bush’s faith-based initiative, though, Obama’s version of the policy has generated loud criticism–from both sides of the aisle–even as the communities that stand to benefit suffer through an ailing economy. Daly believes that many have long misunderstood both the true implications of faith-based partnerships and their unique potential for advancing social justice. God’s Economy serves as a major contribution to the study of American religion and politics.

God’s Economy: Faith-Based Initiatives and the Caring State, a recent University of Chicago Press publication by Lew Daly brings to the fore the intellectual history of the faith-based initiative. Digging through the Daniel Coats Papers, Daly, a senior fellow at Demos, a nonpartisan public policy research and advocacy organization, traces the roots of the faith-based initiative to the pluralist tradition of Europe’s Christian democracies, in which the state shares sovereignty with social institutions. Daly argues that Catholic and Dutch Calvinist ideas played a crucial role in the evolution of this tradition, as churches across nineteenth-century Europe developed philosophical and legal defenses to protect their education and social programs against ascendant governments. Daly untangles the radical beginnings of the faith-based initiative and the influence of this heritage on the past three decades of American social policy and church-state law. Daly also makes an effort to free the concepts from the narrow culture-war framework that has limited debate on the subject since Bush opened the White House Office for Faith-Based and Community Initiatives in 2001 and as President Obama signals a sharp break from many Bush Administration policies. Like Bush’s faith-based initiative, though, Obama’s version of the policy has generated loud criticism–from both sides of the aisle–even as the communities that stand to benefit suffer through an ailing economy. Daly believes that many have long misunderstood both the true implications of faith-based partnerships and their unique potential for advancing social justice. God’s Economy serves as a major contribution to the study of American religion and politics.

All posts by David Malone

Larger Than Life! — new video bio of Red Grange

A new video documentary on the life of Harold “Red” Grange, creatively told through the backdrop of the creation of a new Grange statue commissioned by the University of Illinois, has been recently produced by the University and broadcast on the Big Ten Network. Grange was a sports superstar that transformed professional football and helped firmly establish the National Football league. Together with C. C. Pyle, Grange became a model for sports celebrity, marketing and endorsements. Now available online, the 45-minute long biographical production, Larger Than Life: the Red Grange story, weaves the story of Grange’s career with George Lundeen’s creation of the statue and is full of primary source materials and interviews with sports historians and other noted individuals. One of the historians interviewed is Gary Andrew Poole, author of The Galloping Ghost: Red Grange, an American football legend. As with Poole’s book, the University of Illinois utilized several images from the Grange collection that are unique to our holdings in its production.

A new video documentary on the life of Harold “Red” Grange, creatively told through the backdrop of the creation of a new Grange statue commissioned by the University of Illinois, has been recently produced by the University and broadcast on the Big Ten Network. Grange was a sports superstar that transformed professional football and helped firmly establish the National Football league. Together with C. C. Pyle, Grange became a model for sports celebrity, marketing and endorsements. Now available online, the 45-minute long biographical production, Larger Than Life: the Red Grange story, weaves the story of Grange’s career with George Lundeen’s creation of the statue and is full of primary source materials and interviews with sports historians and other noted individuals. One of the historians interviewed is Gary Andrew Poole, author of The Galloping Ghost: Red Grange, an American football legend. As with Poole’s book, the University of Illinois utilized several images from the Grange collection that are unique to our holdings in its production.

New Shades of Evangelicalism — Jesus and Justice

Utilizing numerous collections in the holdings of Wheaton College, Peter Goodwin Heltzel has recently published Jesus and Justice: Evangelicals, Race, and American Politics (Yale University Press). Receiving very positive responses Heltzel’s book looks into American religion and its difficult relationship with cultural forces such as politics, slavery, race and justice through the lens of four evangelical social movements: Focus on the Family, Christian Community Development Association, the National Association of Evangelicals, and Sojourners. The Wheaton College Archives & Special Collections houses the records of the latter two organizations. Through these lenses Heltzel traces the roots of contemporary evangelical politics to the prophetic black Christianity tradition of Martin Luther King, Jr. and the socially engaged evangelical tradition of Carl F. H. Henry. Heltzel shows that the basic tenets of King’s and Henry’s theologies have led their evangelical heirs toward a prophetic evangelicalism and engagement with poverty, AIDS, and the environment — shining new light on the ways evangelicals shape and are shaped by broader American culture.

Utilizing numerous collections in the holdings of Wheaton College, Peter Goodwin Heltzel has recently published Jesus and Justice: Evangelicals, Race, and American Politics (Yale University Press). Receiving very positive responses Heltzel’s book looks into American religion and its difficult relationship with cultural forces such as politics, slavery, race and justice through the lens of four evangelical social movements: Focus on the Family, Christian Community Development Association, the National Association of Evangelicals, and Sojourners. The Wheaton College Archives & Special Collections houses the records of the latter two organizations. Through these lenses Heltzel traces the roots of contemporary evangelical politics to the prophetic black Christianity tradition of Martin Luther King, Jr. and the socially engaged evangelical tradition of Carl F. H. Henry. Heltzel shows that the basic tenets of King’s and Henry’s theologies have led their evangelical heirs toward a prophetic evangelicalism and engagement with poverty, AIDS, and the environment — shining new light on the ways evangelicals shape and are shaped by broader American culture.

New Red Grange book by Lars Anderson available

Lars Anderson, author of Carlisle vs. Army: Jim Thorpe, Dwight Eisenhower, Pop Warner, and the forgotten story of football’s greatest battle, has just had The First Star: Red Grange and the barnstorming tour that launched the NFL published by Random House. This book follows on the heels of Gary Poole’s biography of Harold Edward Grange. Anderson delves more into the early days of Grange’s professional career — the barnstorming tour that took Grange east to New York, south to Florida, and, finally west to the Pacific coast. The barnstorming tour was brutal and likely contributed to Grange’s shortened injury-laden career. Grange finished playing college ball on November 21, 1925. Five days later he was playing pro-ball on Thanksgiving, much to the shock and dismay of many. The barnstorming tour began after Grange helped the Bears for two games in Chicago as their season was winding down. The tour went through St. Louis, Philadelphia, New York, Washington, Boston, Pittsburgh, and Detroit, over an eleven-day period, before returning to Chicago for another home game on December 13th. Then the tour, beginning on Christmas Day, 1925, took a second leg of nine games to Coral Gables, Florida, ending in Seattle on Jan. 31, 1926. The allure of the barnstorming tour and its profits caused tension between Grange, his manager C. C. Pyle and George Halas. By the next season Pyle had created a start-up rival football league with Grange as its, unbeknownst, injured star. The plan failed and Grange returned, somewhat hat-in-hand, to Halas and his Chicago Bears — never really the same physically. Grange had changed professional football, but it also taken its toll personally.

Lars Anderson, author of Carlisle vs. Army: Jim Thorpe, Dwight Eisenhower, Pop Warner, and the forgotten story of football’s greatest battle, has just had The First Star: Red Grange and the barnstorming tour that launched the NFL published by Random House. This book follows on the heels of Gary Poole’s biography of Harold Edward Grange. Anderson delves more into the early days of Grange’s professional career — the barnstorming tour that took Grange east to New York, south to Florida, and, finally west to the Pacific coast. The barnstorming tour was brutal and likely contributed to Grange’s shortened injury-laden career. Grange finished playing college ball on November 21, 1925. Five days later he was playing pro-ball on Thanksgiving, much to the shock and dismay of many. The barnstorming tour began after Grange helped the Bears for two games in Chicago as their season was winding down. The tour went through St. Louis, Philadelphia, New York, Washington, Boston, Pittsburgh, and Detroit, over an eleven-day period, before returning to Chicago for another home game on December 13th. Then the tour, beginning on Christmas Day, 1925, took a second leg of nine games to Coral Gables, Florida, ending in Seattle on Jan. 31, 1926. The allure of the barnstorming tour and its profits caused tension between Grange, his manager C. C. Pyle and George Halas. By the next season Pyle had created a start-up rival football league with Grange as its, unbeknownst, injured star. The plan failed and Grange returned, somewhat hat-in-hand, to Halas and his Chicago Bears — never really the same physically. Grange had changed professional football, but it also taken its toll personally.

Let not man put asunder…

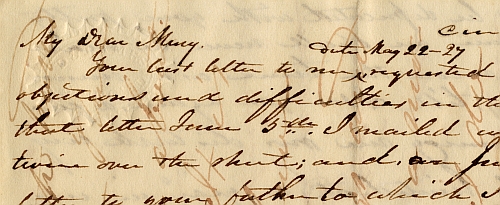

Throughout the summer of 1838 Jonathan Blanchard had thoughts of marriage on his mind, particularly, the thought of Mary Avery Bent who was residing in her natal Middlebury, Vermont after spending time as a teacher in Pennsylvania and Alabama. The correspondence between Jonathan and Mary, as well as between Jonathan and Mary’s father clearly gives one the sense of significance and weightiness of the prospect of their future together. In this time and place marriage was not entered into lightly and contrasts greatly with today’s expendable marriages.

Throughout the summer of 1838 Jonathan Blanchard had thoughts of marriage on his mind, particularly, the thought of Mary Avery Bent who was residing in her natal Middlebury, Vermont after spending time as a teacher in Pennsylvania and Alabama. The correspondence between Jonathan and Mary, as well as between Jonathan and Mary’s father clearly gives one the sense of significance and weightiness of the prospect of their future together. In this time and place marriage was not entered into lightly and contrasts greatly with today’s expendable marriages.

What wasn’t on Jonathan’s mind, until rather suddenly, was the role that he would play in someone else’s marriage. By June 1838 Jonathan Blanchard had associated himself to and begun to assume leadership of the Sixth Presbyterian Church in Cincinnati, Ohio. Here he followed in the footsteps of Asa Mahan who went on to lead Oberlin College. At this time without the credentials to perform marriages he was asked by a very recent member of the church if he could secure the ability to solemnize marriages. In his own words to Mary, his beloved, Jonathan wrote on June 27, 1838

“A young lady joined to my church last communion is going to be married in a few days and she got her mother to ask me in [time] so that I might get my license from the court before her intended should apply to me — so that I am now clothed with the necessary powers — and — do you believe — my first official act is to join a couple of colored people in marriage which I am to-night to do! I dare not tell any of Mary Cobb’s (for that is her name) friends of it for fear the association of ideas will not be calculated to add to the bliss of their union. Mary is a girl from N. England of limited advantages but a pretty face, and decided piety. Her (to be) husband is a rather fine looking young man — professedly pious — will do — though not so good as she is. She however, will always make him mind.”

Blanchard, known to preach in black churches and ridiculed for it, resisted the sinful racial structures of the day. It is a testament to Jonathan Blanchard that he was willing, in these times, to have his first wedding ceremony be between a black man and woman. He provided for these free-persons a service often unavailable to their enslaved kinsmen and kinswomen. This wedding and his involvement in the Cincinnati Underground Railroad expresses Blanchard’s putting his beliefs into action and showed that he was no “respecter of persons” as so many of his contemporaries were.

The Fourway Test

One of the most influential philanthropists of Evangelicalism in the mid-twentieth century was Herbert J. Taylor. Taylor, born in in Pickford, Michigan in 1893, had been educated at Northwestern University and began a career in business, initially in Oklahoma. After a time in the Navy during World War I Taylor began working for Jewel Tea Company (later Jewel Food Stores), eventually becoming an executive in the company. In 1933 Taylor was “loaned” to Club Aluminum Products, a door-to-door kitchen products sales company which was started in the early 1900s, when the company went into bankruptcy. Upon taking over Club Aluminum Taylor found that the business practices at the company were not above reproach and sought a way to turn the company around financially and ethically. While at Club Aluminum Taylor created a simple ethical code that became known as The Four Way Test. The test consisted of four short questions:

- Is it the truth?

- Is it fair to all concerned?

- Will it build goodwill and better friendships?

- Will it be beneficial to all concerned?

This code, created in 1932, established a common working environment for Club Aluminum and helped make the company profitable, trustworthy and strong.  Within several years the company was out of debt and became a multi-million dollar company.

Within several years the company was out of debt and became a multi-million dollar company.

During this time Taylor was a member of the Chicago Rotary Club and eventually became president of the club. And in 1944 he was selected International Director of Rotary. It was then that he offered the test to Rotary. The organization adopted The Four Way Test and has promoted it around the world to encourage an ethical life. It remains a central part of The Rotary despite some who criticized Taylor’s (and Rotary’s) creation of an official “moral code.” Some struggling with the objectification of “truth” and seeking to promote truth’s subjectivity.

From the profits of Club Aluminum Taylor founded the Christian Workers Foundation (CWF) in 1939 and it has helped fund a number of evangelical Christian organizations. Taylor was personally interested in youth work and served on the boards of several youth-oriented organizations like InterVarsity Christian Fellowship, Youth for Christ, Young Life, Child Evangelism Fellowship, Christian Service Brigade and Pioneer Girls. The Christian Workers Foundation continues Taylor’s interests through financial support to many of these organizations.

Herbert Taylor died in 1978. It is said that when the American National Business Hall of Fame wished to honor Taylor a few years after his death they contacted the owners of Club Aluminum to find out information about Taylor. A spokesperson for the company had no knowledge of Taylor.

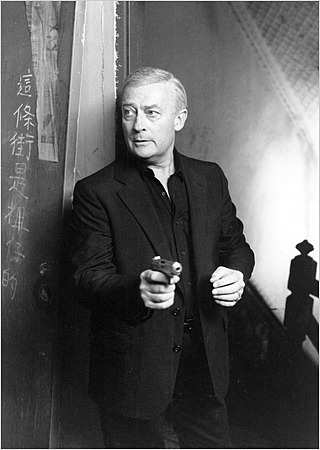

Edward Woodward — TV’s Equalizer

On Monday TV’s Robert McCall, or as he was known to those that truly knew him Edward Woodward, died of pneumonia in his home in Cornwall, England. Woodward had an acting career that had spanned nearly 45 years. He was well-known on the stage, silver-screen and television. Some even knew him for his voice as he recorded recitations and musical albums.

On Monday TV’s Robert McCall, or as he was known to those that truly knew him Edward Woodward, died of pneumonia in his home in Cornwall, England. Woodward had an acting career that had spanned nearly 45 years. He was well-known on the stage, silver-screen and television. Some even knew him for his voice as he recorded recitations and musical albums.

Woodward’s passing is of note to the Archives & Special Collections for the connection that he had with Coleman Luck. Luck worked on The Equalizer series for several years in the mid-1980s. He was co-producer, co-executive producer and senior writer. He valued what Woodward brought to the character of Robert McCall — the “great strength, resolution and energy, coupled with an underlying sorrow.” Despite many attempts in Hollywood to mimic this show and its cast of characters they, according to Luck, failed because “Hollywood misunderstands the meaning of redemption.”

The Luck Papers in the Archives & Special Collections contain numerous scripts and recordings of Woodward’s performances in The Equalizer.

John Q. Public

Many cultures have a name for their “everyman.” In England it is Joe Bloggs or Tommy Atkins. In Poland Jan Kowalski fills the bill. In Puerto Rico you’ll likely bump into Juan Del Pueblo out on the street. In the United States the moniker is John Q. Public. This generic name is used to denote a hypothetical “common man.” This “average joe” represents the randomly selected “man on the street.”

The roots of John Q. Public, according to Hess and Northrop in Drawn & Quartered: the history of American political cartoons, seem to go back to Frederick Opper’s “Mr. Common People” who was the symbol of the average American and appeared in the Arena in 1905. Opper’s character was drawn as a bewildered bald man whose hat was a bit too small and who was subject to the whims of big business’ monopolies and greed. Twenty-five years later as the Great Depression began “John Q. Public” emerged from the pen of Vaughn Shoemaker onto the pages of the Chicago Daily News, where Shoemaker began his career in cartooning in 1922.

Shoemaker’s “everyman” influenced fellow editorial cartoonist Jim Lange’s “Mr. Voter,” a similarly-looking glasses-wearing and mustachioed man clad with a fedora. The Oklahoma State Senate eventually adopted Lange’s character as the state’s official editorial cartoon.

Shoemaker’s editorial cartoons, including those with John Q. Public can be viewed in the Archives & Special Collections.

Poor Pratt – Sesquicentennial Snapshot

In the early years of Wheaton College, one could say in the early decades, as well, the college relied heavily upon the enrollment of local students. Though it broadly drew students from the region, it was the Wheaton community that served as the “bread and butter” of its tuition dollars.

In the early years of Wheaton College, one could say in the early decades, as well, the college relied heavily upon the enrollment of local students. Though it broadly drew students from the region, it was the Wheaton community that served as the “bread and butter” of its tuition dollars.

In 1860 the transition of leadership from Lucius Matlack to Jonathan Blanchard, from the full control of Wesleyan Methodists to the inclusion of Congregationalists, brought new energy and resources. It also brought a different perspective. For over one hundred years a member of the Wheaton College community could not be a member of a secret oath-bound society. Of any sort. The Illinois Institute and, afterward, Wheaton College were founded on several principles: abolition, temperance and anti-secretism. It was these last two, in tension, that brought forth Wheaton College’s encounter with the Illinois legal system.

Edwin Hartley Pratt (1849-1930), a local student, was enrolled in the Academic program at Wheaton. He and several other students joined a local Good Templar’s lodge. Known officially as the Independent Order of Good Templars, this fraternal organization stood for many of the principles that Wheaton, and Jonathan Blanchard, held dear: equality for men and women, racial non-discrimination and temperance. It’s motto sounded very good and biblical — “Friendship, Hope and Charity.” However, it was still a secret society and Jonathan Blanchard would have none of it (having believed that the slave system was the work of secret societies).

So, the administration of Wheaton College (i.e. Jonathan Blanchard), tossed out Pratt and his co-secretists.

In response Pratt’s father sued Wheaton College under the belief and assumption that his son had done nothing illegal and therefore could not be expelled. A legal battle (Pratt v. Wheaton College) ensued that made its way to the Illinois Supreme Court. In a precedent-setting decision the Illinois Supreme Court upheld the right of Wheaton College, and any other school, to establish rules to govern the lives and discipline of its students, much in the same way that a parent would. As the ruling stated, “A discretionary power has been given, … [and] we have no more authority to interfere than we have to control the domestic discipline of a father in his family.” This firmly established the principle of in loco parentis.

In loco parentis is the legal doctrine that outlines a relationship that is similar to that of a parent to a child. The concept goes back hundreds of years and was embedded in English common-law that was borrowed from by American colonists. The Puritans put this idea to use and it found its way into American elementary and high schools, colleges, and universities. The legal system in the nineteenth century was unwilling to interfere when students brought grievances, particularly in the area of rules, discipline, and expulsion. However, this would change in the 1960s as all forms of authority were challenged.

One may wonder what ever happened to Pratt. After leaving Wheaton, he became a noted homeopathic physician and surgeon in Chicago and was known for his professional writing and work. He wrote Orificial Surgery And Its Application To The Treatment Of Chronic Diseases (1891 and dedicated to his father) and The composite man as comprehended in fourteen anatomical impersonations (1901 and published in several editions). He served as President of the Illinois Homoeopathic Medical Association and served on several medical boards and commissions. In 1877 he married Isadore M. Bailey (a Wheaton student from 1875-1877) with the Rev. C. P. Mercer of the Central Swedenborgen Society officiating. Pratt joined the Chicago Society of the New Jerusalem (Swedenborgian) in 1881.

Oddly enough, Pratt v. Wheaton College wasn’t the only time that Pratt was before the Illinois Supreme Court. In 1903 Pratt was sued for not gaining consent before conducting a hysterectomy on a mentally-ill patient. Pratt lost the case and was fined $3,000. He fought the ruling seeking redress before the Supreme Court. Yet, again, the court failed to rule in his favor.

Poor Pratt.

“Three Lady Students in Ministry” – Sesquicentennial Snapshot

In a November 1892 edition of the Wheaton College Record Charles Blanchard, serving as editor, noted three of Wheaton’s “daughters true” who were ordained ministers in their respective denominations. In what would seem as an interesting “reversal” for many today, it was not out of place for these alumnae of Wheaton College to be active leaders in the church. He spoke of these women in glowing terms in a way that clearly confirmed their gifts and calling.

The first ordination of a Northern Baptist (now known as the American Baptist Churches, USA) occurred in 1882. May C. Jones was ordained at a meeting of the Baptist Association of Puget Sound in Washington. Women were generally discouraged from entering the ministry in this denomination. In 1885 Frances E. “Fannie” Townsley became the second-known Baptist woman ordained. Townsley had begun preaching in churches and holding evangelistic services throughout New England in 1875. She was licensed to preach by her church in Shelburne Falls, Massachusetts and several years later moved to Fairfield, Nebraska. There she pastored Fairfield Baptist Church. After serving successfully as an evangelist for twelve years Townsley still lacked ordination and the ability to administer sacraments. The deacons of Fairfield asked to ordain her. After resisting this move for several months Townsley consented to ordination in April 1885. Her ordination exam took three hours and covered, as well, her sense of call and doctrinal views.

The first ordination of a Northern Baptist (now known as the American Baptist Churches, USA) occurred in 1882. May C. Jones was ordained at a meeting of the Baptist Association of Puget Sound in Washington. Women were generally discouraged from entering the ministry in this denomination. In 1885 Frances E. “Fannie” Townsley became the second-known Baptist woman ordained. Townsley had begun preaching in churches and holding evangelistic services throughout New England in 1875. She was licensed to preach by her church in Shelburne Falls, Massachusetts and several years later moved to Fairfield, Nebraska. There she pastored Fairfield Baptist Church. After serving successfully as an evangelist for twelve years Townsley still lacked ordination and the ability to administer sacraments. The deacons of Fairfield asked to ordain her. After resisting this move for several months Townsley consented to ordination in April 1885. Her ordination exam took three hours and covered, as well, her sense of call and doctrinal views.  As one might expect for the times, Townsley endured criticism and resistance after her ordination. She would later travel frequently to preach in towns throughout Nebraska, and served as a temperance leader. She supplied three pastorates in Nebraska then resumed evangelistic work. She filled a number of Baptist pulpits for months. Her last charge was the Covenant of Chicago. Years later, around the turn of the century Townsley, living in Maywood, Illinois, had an award-winning essay published by the Women’s National Sabbath Alliance. Townsley also served as an editor for The Union Signal, the official paper of the Women’s Christian Temperance Union.

As one might expect for the times, Townsley endured criticism and resistance after her ordination. She would later travel frequently to preach in towns throughout Nebraska, and served as a temperance leader. She supplied three pastorates in Nebraska then resumed evangelistic work. She filled a number of Baptist pulpits for months. Her last charge was the Covenant of Chicago. Years later, around the turn of the century Townsley, living in Maywood, Illinois, had an award-winning essay published by the Women’s National Sabbath Alliance. Townsley also served as an editor for The Union Signal, the official paper of the Women’s Christian Temperance Union.

Jennie Hewes Caldwell served, with great success, as an evangelist among the Methodist churches of the United States and Great Britain. She was, at one time, a teacher at Wheaton College and was remembered for her care and concern for her students.

Miss Juanita Breckenridge was the ordained pastor of the Brooktondale Congregational church in Brooktondale. N. Y. and the first female Bachelor’s of Divinity graduate from Oberlin Seminary–the Bachelor’s of Divinity is the equivalent of today’s Master’s of Divinity. Miss Breckenridge caused quite a stir as she sought a license to preach along with her fellow male students while at Oberlin. She was eventually granted the license and ordained.

Miss Juanita Breckenridge was the ordained pastor of the Brooktondale Congregational church in Brooktondale. N. Y. and the first female Bachelor’s of Divinity graduate from Oberlin Seminary–the Bachelor’s of Divinity is the equivalent of today’s Master’s of Divinity. Miss Breckenridge caused quite a stir as she sought a license to preach along with her fellow male students while at Oberlin. She was eventually granted the license and ordained.