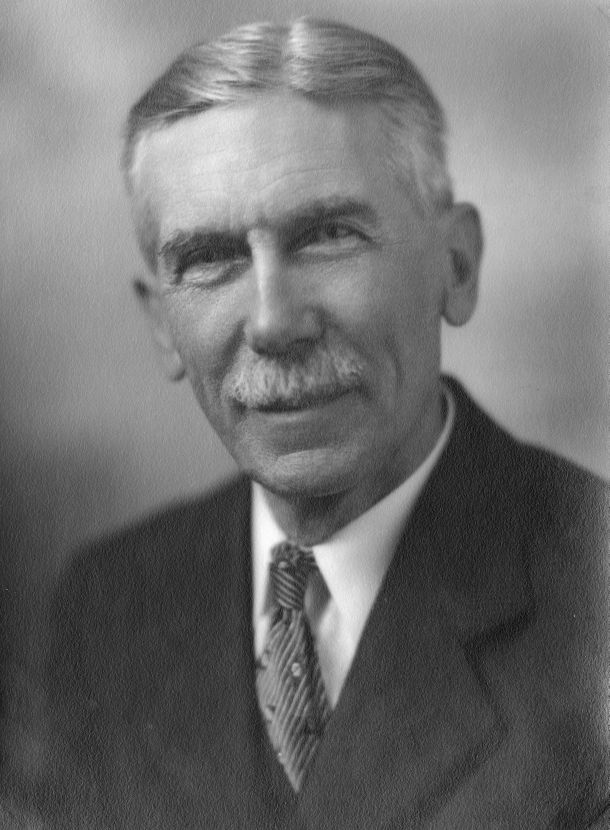

Today it is common for public speakers to adopt informal methods of delivery. Contemporary audiences might see the speaker slouching before them wearing bleached blue jeans with a loose, untucked Hawaiian shirt. In some instances, the speaker might even sit cross-legged on the stage, attempting to establish a friendly bond with his hearers.  However, the notion of excessively easygoing oratory delivered before an expectant auditorium was unfathomable when Dr. Darien Straw (1857-1950), Professor of Rhetoric and Logic and Principal of the Preparatory Department of Wheaton College, published Lessons in Expression and Physical Drill (1892), a consolidation of his classroom wisdom.

However, the notion of excessively easygoing oratory delivered before an expectant auditorium was unfathomable when Dr. Darien Straw (1857-1950), Professor of Rhetoric and Logic and Principal of the Preparatory Department of Wheaton College, published Lessons in Expression and Physical Drill (1892), a consolidation of his classroom wisdom.

He emphasizes that proper posture, efficient gesticulation and precise elocution contribute immeasurably to the intellectual development and future success of the sensibly educated young man or woman. Outward order merely reflects inward stability. “Helping young people to discover ill temper in the voice, carelessness in the walk, selfishness in the bearing and laziness in the words,” writes Straw, “and giving them facility to avoid these, avails more than business proverbs and social precepts.” Throughout the book Straw offers helpful examples.

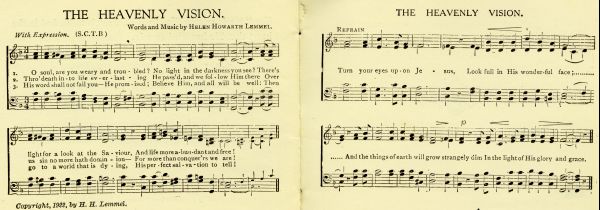

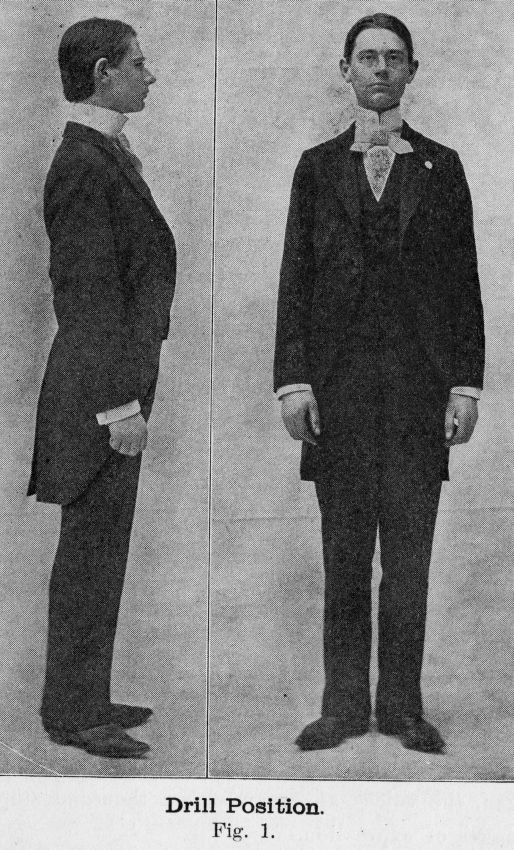

This gentleman stands in the drill position. “Heels together,” writes Straw, “toes turned out from 45 to 90 degrees apart, knees straight, body erect, head well back, chin slightly curbed, chest expanded, arms down at the side with the edge of the hand forward. A good test of erect positon is to stand with the back against a door or other vertical plane so that you can touch it in four places — with the heels, the hips, the shoulders and the head. If you find it difficult to do this there is the more reason for perservering in an erect position. Once the drill position is properly maintained, the student can practice his vocals. Avoid any attempt at loudness,” warns Straw, “but listen to the tone to see if it is correct.”

This gentleman stands in the drill position. “Heels together,” writes Straw, “toes turned out from 45 to 90 degrees apart, knees straight, body erect, head well back, chin slightly curbed, chest expanded, arms down at the side with the edge of the hand forward. A good test of erect positon is to stand with the back against a door or other vertical plane so that you can touch it in four places — with the heels, the hips, the shoulders and the head. If you find it difficult to do this there is the more reason for perservering in an erect position. Once the drill position is properly maintained, the student can practice his vocals. Avoid any attempt at loudness,” warns Straw, “but listen to the tone to see if it is correct.”

Straw later discusses the calculated use of the prone hand and the supine hand. “The primary meaning of the Prone Hand is repression or covering. It is the reverse of the Supine hand, the palm is turned down. It has a great variety of uses, but all related to this primary meaning. The idea of the snow spread upon the earth contains also the idea of a covering. The idea of peace, quiet or stillness contains at the same time suppression of noise or movement and may be expressed by the Prone Hand. There is a gradual shading of this position to that of Averse hand, as we would repress an action or thought disagreeable. As our emotions shade into one another, so our action combines different expressions.”

Straw later discusses the calculated use of the prone hand and the supine hand. “The primary meaning of the Prone Hand is repression or covering. It is the reverse of the Supine hand, the palm is turned down. It has a great variety of uses, but all related to this primary meaning. The idea of the snow spread upon the earth contains also the idea of a covering. The idea of peace, quiet or stillness contains at the same time suppression of noise or movement and may be expressed by the Prone Hand. There is a gradual shading of this position to that of Averse hand, as we would repress an action or thought disagreeable. As our emotions shade into one another, so our action combines different expressions.”

“This, then,” writes Straw, “is an effort to help teachers in giving to pupils the power of self command.”