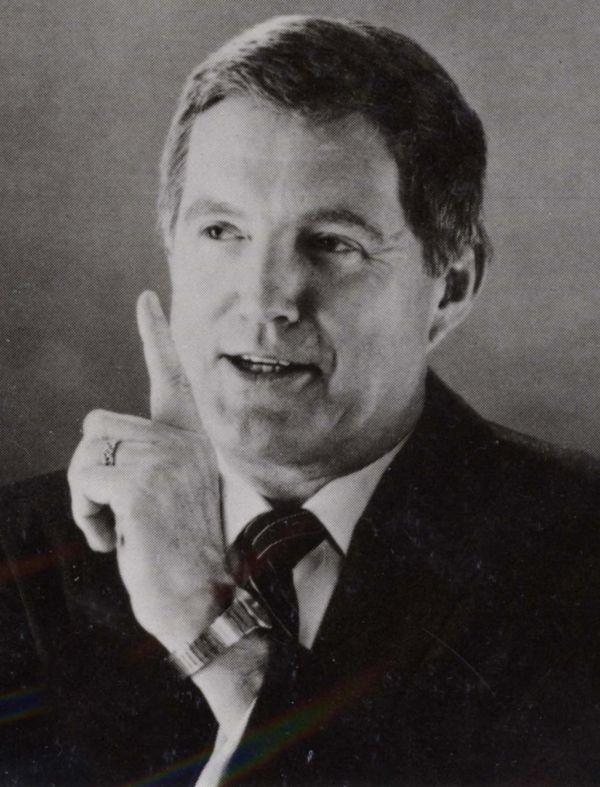

Among the extraordinary individuals who have contributed to the soul of Wheaton College, few were as seasoned as Warren Wyeth Willard. His first book, Steeple Jim, about an alcoholic brawler turned born-again Christian, appeared in 1929 when he was twenty-four. Graduating from Brown University and Princeton Theological Seminary (where he studied under Dr. J. Gresham Machen), Willard had already distinguished himself as an author, businessman, pastor and founder of Camp Good News in Forestdale, MA, before volunteering as a chaplain during WW II. Ministering to spiritually needy soldiers, he landed in 1943 with the 2nd Marine division at the battle at Guadalcanal, and was awarded the Legion of Honor Medal for his service to them during the battle at Tarawa in the Gilbert Islands. According to one report he was “…credited with serving more consecutive days under constant enemy fire than any chaplain in the history of the U.S. Navy and Marine Corps.” In 1944 he was awarded the Legion of Merit, the Navy’s highest honor. Lieutenant Willard’s stirring wartime chronicle, The Leathernecks Come Through, brought him national fame; and in February, 1944, he was invited by Wheaton College to deliver its mid-winter evangelistic services. So impressed were staff and students with this heroic 39-year-old, that it was decided to hire him as Director of Evangelism and Assistant to President V. Raymond Edman. Willard, moving his wife, Grace, and their children from Cape Cod to 821 Irving Avenue, settled easily into his administrative responsibilities. He offers a candid glimpse:

Among the extraordinary individuals who have contributed to the soul of Wheaton College, few were as seasoned as Warren Wyeth Willard. His first book, Steeple Jim, about an alcoholic brawler turned born-again Christian, appeared in 1929 when he was twenty-four. Graduating from Brown University and Princeton Theological Seminary (where he studied under Dr. J. Gresham Machen), Willard had already distinguished himself as an author, businessman, pastor and founder of Camp Good News in Forestdale, MA, before volunteering as a chaplain during WW II. Ministering to spiritually needy soldiers, he landed in 1943 with the 2nd Marine division at the battle at Guadalcanal, and was awarded the Legion of Honor Medal for his service to them during the battle at Tarawa in the Gilbert Islands. According to one report he was “…credited with serving more consecutive days under constant enemy fire than any chaplain in the history of the U.S. Navy and Marine Corps.” In 1944 he was awarded the Legion of Merit, the Navy’s highest honor. Lieutenant Willard’s stirring wartime chronicle, The Leathernecks Come Through, brought him national fame; and in February, 1944, he was invited by Wheaton College to deliver its mid-winter evangelistic services. So impressed were staff and students with this heroic 39-year-old, that it was decided to hire him as Director of Evangelism and Assistant to President V. Raymond Edman. Willard, moving his wife, Grace, and their children from Cape Cod to 821 Irving Avenue, settled easily into his administrative responsibilities. He offers a candid glimpse:

I could write another book entitled, “My Five Years at Wheaton College”…What were my duties as “Assistant to the President?” Just that – assisting the president. And believe me, by the grace of God, I was a faithful one. Modesty prevents me from using more descriptive words.

As I came to know him at private devotions held each morning in his office, then through conferences which followed these devotions, by observing his far-reaching influence on the student body, I was glad to give him my whole-hearted support. I had been indoctrinated in the Navy with the slogans of “Loyalty up and loyalty down” and “All for one and one for all.” It was easy to be loyal to Dr. Edman. As we daily walked together across the campus for the college chapel worship services, he would greet a hundred students and call them by their first names. He counseled with them in his office as would a father. There was a quiet dignity, sympathy and pathos in his voice as he led them into the deep things of God. He loved them all as though they were his sons and daughters. After they had graduated, he followed them as a guardian angel…

Aside from preaching challenging messages to the campus, Willard raised funds for Wheaton Academy and recruited members for the Board of Trustees. Edman also tasked him with writing the first formal history of the college, Fire on the Prairie (1950). In 1951, the self-described “old goat of 46 years,” seeking to sharpen his reasoning skills, departed Wheaton to study law at Northwestern University in Chicago, there earning his Doctor of Jurisprudence. But the pulpit called him away from a legal career, and he returned to the ministry as pastor of Third Baptist Church in Barnstable on Cape Cod. “What a delightful four years were spent serving in this quaint little church!” he recalls. Then, in 1960, he was unanimously called to First Presbyterian Church of Waltham, MA, where he served for 22 years before retiring. The concluding sentiment of his memoir, Confessions of a Minister (1975), humbly recognizes the immovable northstar of his life:

In my early teens, when I began to read daily from the New Testament and understand its message, something happened in my heart. I fell in love with Jesus Christ. From that day to this, I have loved him and attempted to serve him with all the passion and intensity of my soul. So may it be until the day I die – a death that will have no sting, a grave that will have no victory. For me to live is Christ, and to die is gain (Philippians 1:21 RSV).

He died in 2000 at age 94 in Sandwich, Massachusetts.