by Dr. Zondra Lindblade ’55

The great blue heron is perfectly camouflaged against the lakeshore pines. The green caterpillar is protectively colored on the begonia leaf. Camouflaged treasures are everywhere, but experienced northwoods eyes see beyond the pines and begonias to recognize the disguised.

The great blue heron is perfectly camouflaged against the lakeshore pines. The green caterpillar is protectively colored on the begonia leaf. Camouflaged treasures are everywhere, but experienced northwoods eyes see beyond the pines and begonias to recognize the disguised.

In many ways, a “sociological imagination” resembles northwoods eyes and wilderness expediency. The imagination first examines obvious features of how we live together in families, corporations, and in society, and then probes beneath the surface to “see” camouflaged functions and meanings. What is camouflaged often surprises and sometimes contradicts conventional wisdom.

The sociological imagination is a filter, a directional lens that focuses on the obvious and hidden human experiences. Once awakened to the reality of groups being more than the sum of individual parts, the filter questions and educates the illusive realities that question “what everyone knows.”

For some time the issues of social welfare reform have occupied our “imagination.” These stimuli have opened my eyes and heart to a particular phrase in Micah 6:8.The call to “do justice” in this verse is resounding for sociologists who study cause and effect of social stratification, stigmatized education, or inner-city miseries. These are vacuous academic activities if there is no heart cry for justice. God’s command in Micah 6 to do justice is daunting.

In the next phrase, God requires believers to actually love mercy. A desire for justice may overlook and camouflage God’s compelling love for mercy. Mercy is assistance given to those who do not deserve help–or who think they do not. Mercy is a reflection of God’s character (Ps. 69:16) and part of His plan for repentance (Rom. 2:4).

What does it mean–to love mercy? Discussions of welfare reform usually ignore the priority God places on mercy. Do we consider mercy nalve, ill-informed, and shortsighted because mercy is offered before merit? Mercy does not consider independent responsibility as a first–order priority. Do we focus on eradicating dependency and setting the welfare mother on is both fulfilling to her and good for society? Are we occupied with making sure that sinful choices bring hard consequences? Are we slow to persevere when lessons experienced are not learned, when positive change is one step forward followed by four steps back?

Mercy may well invoke a “reckless advocacy” for the marginalized and undeserving. Mercy might offer help with no questions asked or answers expected. The example of the Savior is strong and convincing. He is a reckless advocate who “while we were yet sinners died for us.”

In my 34 years of teaching, occasionally there have been undeserving Wheaton students who have requested academic mercy from me. I have found that the students who received that mercy remember this help with greater appreciation than most of the assignments diligently pursued. And mercy remembered is often mercy later given.

———-

Twenty years ago, the Wheaton Alumni magazine began a series of articles, titled “On My Mind”, in which Wheaton faculty told about their thinking, their research, or their favorite books and people. Former Professor of Sociology Emerita, Zondra Gale Lindblade Swanson ’55 (who taught at Wheaton from 1964-1998) was featured in the Autumn 1998 issue. Dr. Lindblade was former department chair and retired in May 1998 after serving the College for more than 34 years.

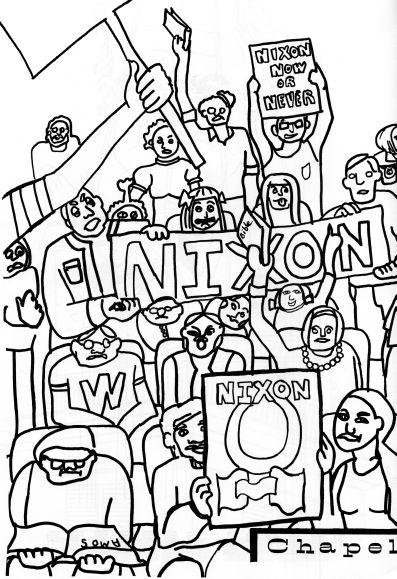

The event was initially suggested by McGovern’s staff, asking for a venue in which he might engage Evangelicals. Activist Jim Wallis, attending Trinity Evangelical Divinity School, was asked to organize the senator’s visit, arranging a breakfast with prominent Christian leaders, in addition to an engagement at Wheaton College. “Actually,” writes Wallis, “the Wheaton Student Council, which issued the invitations to both candidates, accidentally switched the letters, sending Nixon’s by mistake to McGovern.” However, only McGovern accepted. A quiet man raised in a devout Methodist family, McGovern soon found himself in the pulpit of Edman Chapel, standing before an atypically divided house. A few supportive students cheered his unpopular anti-Vietnam War position, but many more booed, waving pro-Nixon banners.

The event was initially suggested by McGovern’s staff, asking for a venue in which he might engage Evangelicals. Activist Jim Wallis, attending Trinity Evangelical Divinity School, was asked to organize the senator’s visit, arranging a breakfast with prominent Christian leaders, in addition to an engagement at Wheaton College. “Actually,” writes Wallis, “the Wheaton Student Council, which issued the invitations to both candidates, accidentally switched the letters, sending Nixon’s by mistake to McGovern.” However, only McGovern accepted. A quiet man raised in a devout Methodist family, McGovern soon found himself in the pulpit of Edman Chapel, standing before an atypically divided house. A few supportive students cheered his unpopular anti-Vietnam War position, but many more booed, waving pro-Nixon banners.

Wallis also remembers:

Wallis also remembers: