Ebay brings forth some of the oddest things around. Sometimes it gives a glimpse into history and sometimes it just plain rips it wide open. Today’s post would fall into the latter category.

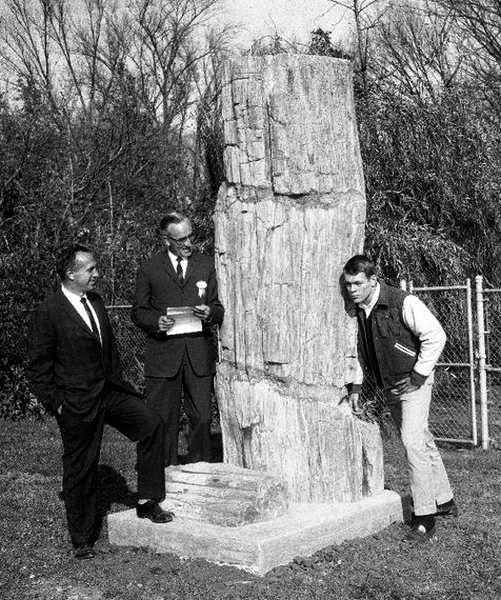

Several months ago, the picture shown here (really the negative) appeared on Ebay. It purported to have been taken on the campus of Wheaton College and clearly had Wheaton connections with the individuals shown. On the far left is football coach Jack Schwartz and next to him is Harv Chrouser, athletic director. Also in the picture is a player, Jim Kielsmeier. Of course, the “800-pound gorilla” in the picture, or more accurately the 7,300 pound item, is a massive petrified oak log. What makes this picture unusual is not the subject matter so much, though this is intriguing, but that this huge log should be on Wheaton’s campus. Geologic specimens on college campuses are not unusual, but what is unusual is when they disappear, especially those of such weight and size.

Several months ago, the picture shown here (really the negative) appeared on Ebay. It purported to have been taken on the campus of Wheaton College and clearly had Wheaton connections with the individuals shown. On the far left is football coach Jack Schwartz and next to him is Harv Chrouser, athletic director. Also in the picture is a player, Jim Kielsmeier. Of course, the “800-pound gorilla” in the picture, or more accurately the 7,300 pound item, is a massive petrified oak log. What makes this picture unusual is not the subject matter so much, though this is intriguing, but that this huge log should be on Wheaton’s campus. Geologic specimens on college campuses are not unusual, but what is unusual is when they disappear, especially those of such weight and size.

The fossilized oak log was said to have been presented to Wheaton College on October 23, 1964. However, today it can’t be found. Where does a four-ton piece of rock go to? And, not just any rock, but one shaped clearly like a log and on a large base? For those unaware, petrifaction occurs when a tree or log is buried underground and is deprived of oxygen and fails to decay. The organic material of the wood is replaced with mineral material such as quartz and the tree or log eventually becomes preserved in a solid “rock” form.

The listing on Ebay sparked several emails to current Geology faculty, all of whom post-date the original gift by several decades, in order to determine the log’s whereabouts. However, the inquiries returned no answers as the log had not been seen during their tenures. Further inquiries continued to turn-up nothing. Diligence paid off as departmental archives were consulted which revealed some correspondence about the petrified log. Now that the connection was verified the whereabouts of the log were still in question. Former faculty were consulted to determine its former location. It certainly had not been stored outside the science building, though it would make a nice monument outside Wheaton’s new science center.

The tale of the lost log continued until recent days when further digging uncovered a connection to Wheaton’s Facilities Management (formerly Physical Plant) staff. The “investigation” indicates that the large oak log had at some time been stored under the football stadium (built in 1956) and roughly a decade ago it needed to be relocated. Somehow a breakdown of communication occurred and the log was broken down and disposed of. Not a simple feat. Accounts indicate that a small piece was salvaged and retained as a personal keepsake.

This tale can certainly illustrate all that can go wrong in an organization as it grows larger and segmentation occurs. Silos emerge and the left hand may not know what the right is doing. Talking about and breaking down the silos may very well be the real “800-pound gorilla.”

When Wheaton Alumni asked me to tell alumni what I am thinking about nowadays, my mind turned to a recent best-seller that both Christian college and public university educators have been talking about for the last three or four years. Alan Bloom complains in The Closing of the American Mind that today’s students talk as if no such things as right or wrong exist; he adds that they have no world-view in which any such values might be grounded, and that as a result they lack a strong sense of personal identity. Instead we hear talk of “alternative lifestyles,” as if morality is simply a matter of personal preferences.

When Wheaton Alumni asked me to tell alumni what I am thinking about nowadays, my mind turned to a recent best-seller that both Christian college and public university educators have been talking about for the last three or four years. Alan Bloom complains in The Closing of the American Mind that today’s students talk as if no such things as right or wrong exist; he adds that they have no world-view in which any such values might be grounded, and that as a result they lack a strong sense of personal identity. Instead we hear talk of “alternative lifestyles,” as if morality is simply a matter of personal preferences. On October 30, 1997

On October 30, 1997