Born in Cedarville, Illinois, on September 6, 1860, Addams graduated from Rockford Female Seminary (now Rockford College) in 1881 where her father, John, served as a trustee. With Ellen Gates Starr Addams founded Hull-House on Chicago’s Near West Side in 1889 to address the social problems associated with urbanization, industrialization, and immigration. Settlement houses, like Hull House, attracted individuals to settle in poor urban neighborhoods and seek to ameliorate social ills. By 1911, Chicago had 35. In its early years Hull-House was located in the midst of a densely populated urban neighborhood of Italian, Irish, German, Greek, Bohemian, and Russian and Polish Jewish immigrants. As is often the case with neighborhoods, over the years the demographics changed. By the 1920s Hull House served African Americans and Mexicans neighbors. In her autobiography Addams recounted the influence of her father to be interested in the “moral concerns of life.”

Jane Addams and the Hull-House residents provided kindergarten and day care facilities for the children of working mothers; an employment bureau; an art gallery; libraries; English and citizenship classes; and theater, music and art classes. As the complex expanded to include thirteen buildings, Hull-House supported more clubs and activities such as a Labor Museum, the Jane Club for single working girls, meeting places for trade union groups, and a wide array of cultural events. The Hull-House residents and their supporters forged a powerful reform movement. Among the projects that they helped launch were the Immigrants’ Protective League, the Juvenile Protective Association, the first juvenile court in the nation, and a Juvenile Psychopathic Clinic (later called the Institute for Juvenile Research). Through their efforts, the Illinois Legislature enacted protective legislation for women and children in 1893. With the creation of the Federal Children’s Bureau in 1912 and the passage of a federal child labor law in 1916, the Hull-House reformers saw their efforts expanded to the national level. In addition, she actively supported the campaign for woman suffrage and the founding of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (1909) and the American Civil Liberties Union (1920). In 1910 she received an honorary doctorate by Yale University–the first ever awarded to a woman by Yale.

Jane Addams and the Hull-House residents provided kindergarten and day care facilities for the children of working mothers; an employment bureau; an art gallery; libraries; English and citizenship classes; and theater, music and art classes. As the complex expanded to include thirteen buildings, Hull-House supported more clubs and activities such as a Labor Museum, the Jane Club for single working girls, meeting places for trade union groups, and a wide array of cultural events. The Hull-House residents and their supporters forged a powerful reform movement. Among the projects that they helped launch were the Immigrants’ Protective League, the Juvenile Protective Association, the first juvenile court in the nation, and a Juvenile Psychopathic Clinic (later called the Institute for Juvenile Research). Through their efforts, the Illinois Legislature enacted protective legislation for women and children in 1893. With the creation of the Federal Children’s Bureau in 1912 and the passage of a federal child labor law in 1916, the Hull-House reformers saw their efforts expanded to the national level. In addition, she actively supported the campaign for woman suffrage and the founding of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (1909) and the American Civil Liberties Union (1920). In 1910 she received an honorary doctorate by Yale University–the first ever awarded to a woman by Yale.

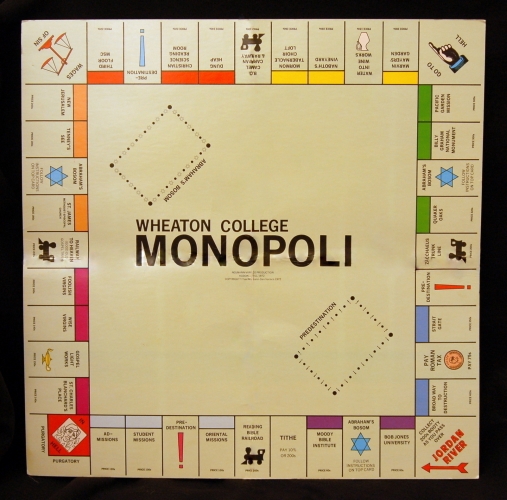

Jane Addams spoke at Wheaton College on March 14, 1894. During her career she wrote prolifically on topics related to Hull-House activities, producing eleven books and numerous articles as well as maintaining an active speaking schedule nationwide and throughout the world. She played an important role in many local and national organizations. Despite being attacked by the press and being expelled from the Daughters of the American Revolution, during World War I Addams worked for peace. As a result of her peace work she was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 1931.

Jane Addams died in Chicago on May 21, 1935. She was buried in Cedarville, her childhood home town.

Sometimes that access can be thwarted by its own openness. While recently verifying the contents of a long-held collection of papers from a long-deceased faculty member (S. Richey Kamm) as the staff of the Archives & Special Collections finish development of our archival management system

Sometimes that access can be thwarted by its own openness. While recently verifying the contents of a long-held collection of papers from a long-deceased faculty member (S. Richey Kamm) as the staff of the Archives & Special Collections finish development of our archival management system