Twenty-five years ago, the Wheaton Alumni magazine began a series of articles entitled “On My Mind” in which Wheaton faculty wrote about their thinking, research, or favorite books and people. Dr. Peter (P.J.) Hill, Professor of Economics Emeritus, was featured in the Winter 2009 issue. Dr. Hill served as the George F. Bennett Professor of Economics at Wheaton from 1986-2011.

Some countries languish in no-growth mode while others flourish. A new economic school of thought provides insights into economic disparity

My discipline has long been termed the dismal science, a description given to economics by historian Thomas Carlyle in the nineteenth century. Indeed, much economic analysis has taken the form of throwing cold water on reforms that will supposedly improve human well-being, arguing that good intentions are not enough and that one needs to carefully think through the incentive effects of any policy change.

More recently, however, one sub-discipline in economics, the New Institutional Economics, has given a positive response to an important question: Why the great differences in income and wealth across societies?

In 1800 the richest countries of the world had per capita incomes about three times that of poor countries. By 2005 this gap had widened so significantly that the per capita incomes of the richest countries were sixty times that of the poor countries.

Almost all of this growing difference is not because of exploitation of the poor by the rich. Instead, the vast gap has arisen because of varied abilities to produce wealth. In other words, some parts of the world have discovered the engine of economic growth, while such growth has bypassed other parts.

Economists have tried numerous explanations for such differences in growth, varying from natural resources to infrastructure to education. All of these have been found to be lacking, especially when embodied in foreign aid programs.

The fundamental cause of economic growth is found in the institutional structure of an economy. The rule of lax protection of property rights, openness to trade, enforcement of contracts, and a stable money supply are all-important for rewarding the individual endeavor that produces increases in economic well-being.

That doesn’t mean other efforts are futile. Microfinance—the making of small loans to individual entrepreneurs—has been successful in numerous settings. A new movement, Business as Mission, also shows real promise. In this endeavor Christians start businesses to glorify God by both creating wealth for all stakeholders and exemplifying biblical principles. Both of these efforts, however, are more likely to thrive in a good institutional environment.

If it is as simple as getting the right institutions in place, why have some countries remained in the no- or slow- growth mode? Usually this is because the elites, or those in control, don’t find such an institutional environment to their advantage. Indeed, when one examines institutions in less developed nations, one often finds that things like property rights and contract enforcement are not easily available to the poor and marginalized.

Therefore, Christians concerned with poverty should work toward a well functioning set of rules, and those rules should give those at the bottom the same access to a fair judicial system and protection of their property as those at the top of the economic order.

[The following statement was included at the time of publication — Wheaton Magazine, Winter 2009] Dr. Peter (P.J.) Hill, the George F. Bennett Professor of Economics at Wheaton, is a Senior Fellow at Property and Environment Research Center in Bozeman, Montana. He is a coauthor of Growth and Welfare in the American Past; The Birth of a Transfer Society; and The Not So Wild, Wild West: Property Rights on the Frontier. He has also written numerous articles on the theory of property rights and institutional change and has edited six books on environmental economics. He is a graduate of Montana State and the University of Chicago. P.J. also owns and operates a ranch in western Montana.

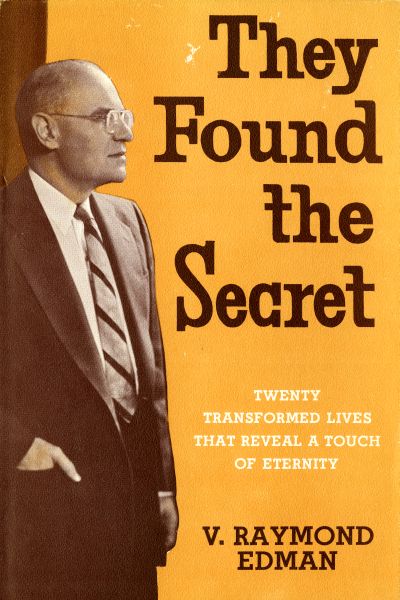

What are the possibilities of the Christian life? To what bold frontiers might our faith aspire? Are a few believers destined for magnificent ministries, while others languish in mediocrity?

What are the possibilities of the Christian life? To what bold frontiers might our faith aspire? Are a few believers destined for magnificent ministries, while others languish in mediocrity?

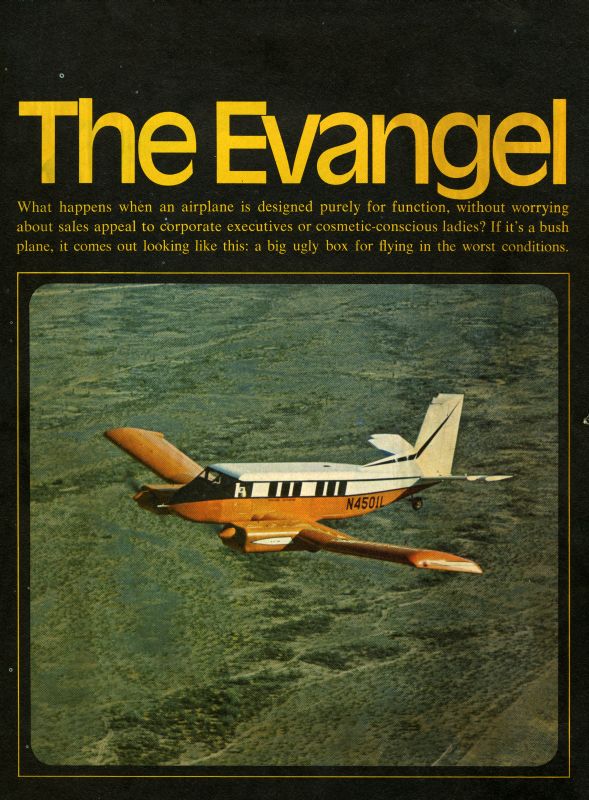

Receiving funding from several Chicago laymen, the Evangel 4500 was ready for its first major mission in 1969. Passengers for thetwo-month voyage to South America were pilot Mortenson, Dr. Paul Wright, chairman of the chemistry department at Wheaton College, and nine other board members of Project Evangel.

Receiving funding from several Chicago laymen, the Evangel 4500 was ready for its first major mission in 1969. Passengers for thetwo-month voyage to South America were pilot Mortenson, Dr. Paul Wright, chairman of the chemistry department at Wheaton College, and nine other board members of Project Evangel. difficulties after surviving the Japanese invasion of their land. Attempting to re-establish their influence, the Thai often exercised hard decisions, such as offering artifacts to visitors they trusted. One family claimed that their lizard skin drum with its abalone mosaics was authentic to the monarchy of either King Mongut or his son, Prince Chulalongkorn, both featured in Margaret Landon’s classic novel, Anna and the King of Siam, which was later reworked by Rodgers and Hammerstein into the popular Broadway musical The King and I.

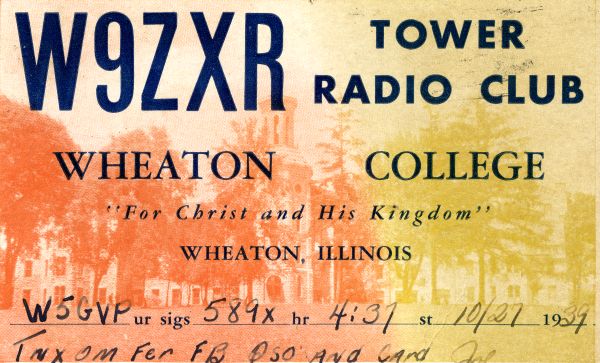

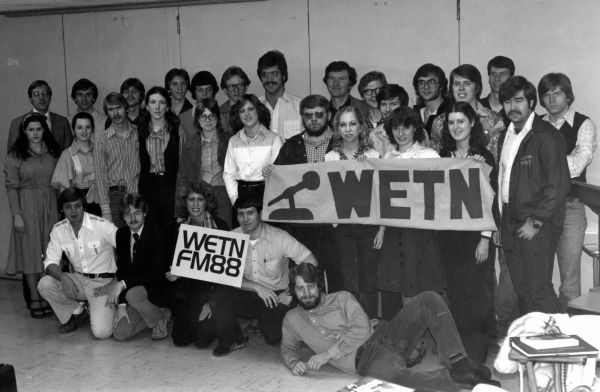

difficulties after surviving the Japanese invasion of their land. Attempting to re-establish their influence, the Thai often exercised hard decisions, such as offering artifacts to visitors they trusted. One family claimed that their lizard skin drum with its abalone mosaics was authentic to the monarchy of either King Mongut or his son, Prince Chulalongkorn, both featured in Margaret Landon’s classic novel, Anna and the King of Siam, which was later reworked by Rodgers and Hammerstein into the popular Broadway musical The King and I. 2016 marks the final year in which the hard copy of Wheaton College yearbook, The Tower, is published. Due to budgetary restraints and relative lack of interest among students, the administration decided to cease publication. From this point forward information will be collected digitally. Collectively, the yearbooks cover approximately 2/3 of the college’s 156-year life, capturing for posterity priceless moments and pertinent personal information.

2016 marks the final year in which the hard copy of Wheaton College yearbook, The Tower, is published. Due to budgetary restraints and relative lack of interest among students, the administration decided to cease publication. From this point forward information will be collected digitally. Collectively, the yearbooks cover approximately 2/3 of the college’s 156-year life, capturing for posterity priceless moments and pertinent personal information. Years later Saint’s brother, Nate, would die with Jim Elliott and four other missionaries at the hands of Waorani tribesmen in Ecuador.

Years later Saint’s brother, Nate, would die with Jim Elliott and four other missionaries at the hands of Waorani tribesmen in Ecuador.