Twenty years ago, the Wheaton Alumni magazine began a series of articles, titled “On My Mind”, in which Wheaton faculty told about their thinking, their research, or their favorite books and people. Professor of German Emerita Carol Joyce Kraft (who taught at Wheaton from 1960-1996) was featured in the Autumn 1995 issue.

There are two clocks in my office. One hangs on my wall and is powered by a battery. The other stands on my desk and needs winding every day.

There are two clocks in my office. One hangs on my wall and is powered by a battery. The other stands on my desk and needs winding every day.

Even though I sit between the two, when my mind is on course work, that mound of detailed mental activity calling loudly for attention, I hear the small clock. Ticktickticktick.

During those times when someone has come to the office to speak of personal matters, the pace is slower and more relaxed. We listen to each other, and somewhere in the midst of that discussion I have noticed that I always hear the slower clock. Tick…tick…tick…tick…. The other clock, the one that suggests a frantic pace, seems to have disappeared.

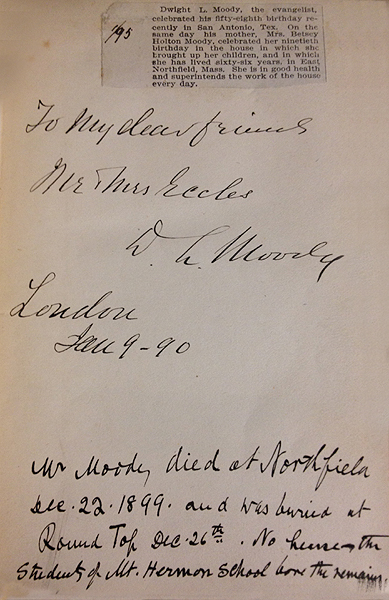

Two clocks. Why do I mention them? For the past few years in our twentieth century German literature course we have read and discussed some themes in the recent work, Momo, by Michael Ende. This is a modern fairy tail for adults, one which remained on Germany’s best-seller list for many months in 1983.

What was it that drew so many readers? Could it be that they saw themselves in that skillfully drawn reflection of modern life?

Momo is the story of a young orphan girl who listens to people. She is one who gives all who will come that valuable gift of rapt attention.

We soon notice, however, that there are gray figures who have appeared in the city. They are everywhere and they all look alike: gray coats, gray hats, gray briefcases, gray cars, ashen gray faces, As we listen in on one, we discover that he is trying to persuade a barber that it would really be to his advantage to save more time. He begins to list all the things that Herr Fusi, the barber, does when he is away from his shop. He eats, he sleeps, he visits his deaf mother daily, he cleans his house, he reads, he spends time with friends, he sings in a choir, he visits a crippled young girl, and he even spends 15 minutes at the end of his day meditating over what has transpired since the morning began.

All this time is lost, misspent, useless, says der Graue. Why it’s about half of your life, Herr Fusi! The solution? Zeitsparen. You have to save time. How do you do that? Work faster, Herr Fusi! Omit the “extras.” The time that you save, we’ll put in the savings bank, with interest. The amount you save will double every five years! We don’t force anyone, mind you, but it’s really to your advantage. Think about it. Time is money.

Herr Fusi thinks about it. He decides. It is as though he is compelled to speed up his work. And we watch him very gradually become less than a Mensch, less than a human being. He becomes a machine. And so do his friends. And most everyone else in the city. They become hardly recognizable anymore. They have no time to think. No time to listen. No time for the heart. No time for the family. No time to be. Robots are what they have become. The tragedy is that they don’t know it; they don’t recognize what they have become; or if they begin to realize what has happened, they see no way out. They find themselves trapped in their frenzy. The more time they save, the less they have. They have been trapped by a lie.

What an image!

It is the children in the story who see clearly that something is amiss in the world of grown-ups. It is the children, through Momo, who bring sanity back to the city. It is the children who restore a healthy sense of time. They recognize that time is not money. They know that time is a matter of the heart. (The remainder of the story I will leave for your reading.)

Although I don’t agree with one of the main thoughts, that time is everything, I do agree with the author’s main thrust, that time cannot be “saved” for later. Time is for now. It is precious and it is only used once. The more time we save, the less we really have.

So, ours also is a world of clocks. Which one is it that we hear? The one with the frantic pace or the one that allows us pauses to live?

I chose this topic of time because there are moments in the classroom when I am reminded that James (3:1) was right when he reminds us that not many should become teachers. It is an overwhelmingly humbling experience when you sense that someone has acted on the suggestions you have made. So what is it that we are reflecting, by our words, by our lives, by the way we make use of our time?

———-

The following statement was included at the time of publication: Carol J. Kraft ’57 received the B. A. from Wheaton, an M A. in the Teaching of Foreign Languages front Teacher’s College, Columbia University, and an M .A. in Germanic Language and Literature from the University of Michigan. She took additional graduate study at Middlebury College and has participated in several summer programs in the Goethe Institute in Germany. She has served as a member of the Foreign Language Department since 1960. Another strong area of interest is that of Spiritual Direction, which is a part of her responsibilities as ordained deacon in the Episcopal Church, Diocese of Chicago, serving at St. Barnabas’ in Glen Ellyn.

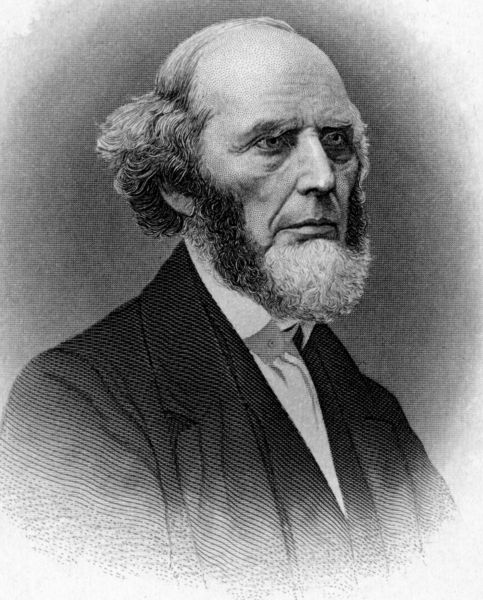

Laying the groundwork for all such ministries, however, was Charles Grandison Finney (1792-1875), the first great evangelist of the Second Great Awakening, who established such familiar patterns as offering the public invitation (now known as the “alter call”) to sinners to accept Christ’s free gift of grace, encouraging them to walk forward and deal with God at an “anxious bench;” and praying extemporaneously from the pulpit, rather than reading from a book. Finney’s innovations, now common practice, were groundbreaking for American Protestantism. As such his influence deeply colored the spirit of Wheaton College, though he never visited its campus.

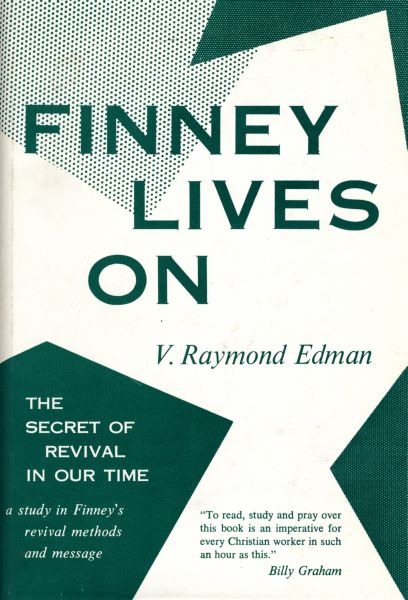

Laying the groundwork for all such ministries, however, was Charles Grandison Finney (1792-1875), the first great evangelist of the Second Great Awakening, who established such familiar patterns as offering the public invitation (now known as the “alter call”) to sinners to accept Christ’s free gift of grace, encouraging them to walk forward and deal with God at an “anxious bench;” and praying extemporaneously from the pulpit, rather than reading from a book. Finney’s innovations, now common practice, were groundbreaking for American Protestantism. As such his influence deeply colored the spirit of Wheaton College, though he never visited its campus. In 1951 Edman published Finney Lives On: The Secret of Revival in Our Time, of which Billy Graham remarks, “To read, study and pray over this book is an imperative for every Christian worker in such an hour as this.” Edman summarizes his subject in the epilogue:

In 1951 Edman published Finney Lives On: The Secret of Revival in Our Time, of which Billy Graham remarks, “To read, study and pray over this book is an imperative for every Christian worker in such an hour as this.” Edman summarizes his subject in the epilogue: