The following article details the life of teacher, performer and author Elizabeth Green ’28. The interview was featured in the Wheaton College Alumni Magazine in June 1987 and is transcribed below.

A Vibrant Chord in the Abundant Life

A Vibrant Chord in the Abundant Life

by Jean Harmeling ’78

Elizabeth Green’s zeal for life and learning has blended harmoniously with a distinguished music career full of surprises. At the age of nine, she announced emphatically that she “would never teach.” More than 70 years later, she is recognized as one of the most important and highly esteemed teachers of stringed instruments and conducting in America. Her books are used in classrooms in major universities, and her associations with some of the greatest violinists and conductors in the world still put her in high demand as a lecturer.

“Well,” she comments ironically, her voice always sparking with laughter, “I guess the Lord knew differently.”

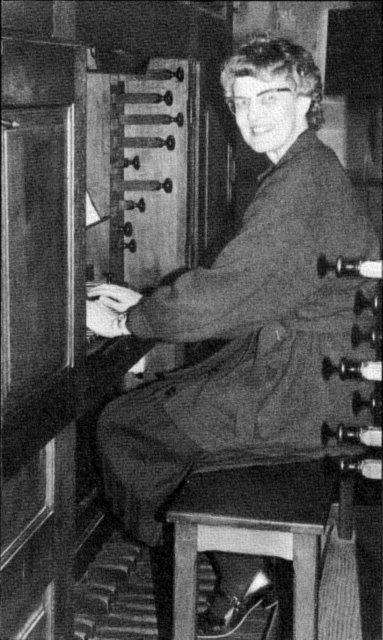

Elizabeth Green ’28 never questioned her love for the violin, however. Taught by her father, Albert Green, Wheaton Conservatory’s first director, she gave her first public performance at age five. By the time she reached high school, “she was playing rings around me,” remembers lifelong friend, Leslie Blasius, a Conservatory graduate in 1923. “She had outstanding, remarkable technique at such an early age.”

Elizabeth remembers her years at Wheaton as being “the strongest influence of my life,” not only as a teacher and writer, but in her faith as well. “I owe the depth of my religion to Wheaton.”

After a fire destroyed her family’s home in 1922, she moved into Williston dorm. There she became seriously ill with the flu and nearly died. A prayer meeting was held outside her door all night, and the next day she began to recover. “I believe those prayers saved my life,” she recalls.

Bouncing right back, Green finished her music degree requirements at Wheaton before she finished high school. She was allowed to “walk down the aisle” for the 1923 graduation ceremonies, but since she hadn’t completed the academic requirements for her degree, she stayed on at Wheaton until 1928 when she received a B.S. in philosophy with a minor in physics. Her continued musical studies included viola with Clarence Evans, principal violist with the Chicago Symphony, and violin with Jacques Gordon, concertmaster, also with the Symphony.

After Wheaton, Elizabeth took on the formidable task of teaching stringed instruments in the Waterloo, Iowa, public schools and organizing the Waterloo Symphony in which she also performed. By 1939, she had also completed her master of music degree from Northwestern University.

Impressed with the awards her students were winning at state and national orchestra festivals, the University of Michigan at Ann Arbor presented Green with a new challenge. In 1942 she was invited to teach the orchestral program for the Ann Arbor public schools. Accepting the challenge, Green transformed the Ann Arbor High School “orchestra” from a struggling nine-member group into a 60-piece symphony, then left the public schools in 1954 to teach full-time at the University for the next 20 years.

Her performance career expanded as well as soloist and concertmaster with the Ann Arbor and Saginaw Symphonies, experiences she looks back on with special joy. She performed and conducted for numerous other symphonies from around the country, but never gave up her desire for learning more.

From 1949 to 1956, Green spent her summers studying violin with world-renowned Ivan Galamian. During this time, she also helped him write his book Principles of Violin Playing and Teaching (1962). Today, Green is considered a leading authority on Galamian’s methods of violin pedagogy.

Her writing skills were also called upon to finish the late Nicolai Malko’s book The Conductor and His Score (1971). Green had a long association with the great Russian composer. In 1965, four years after his death, the Nicolai Malko Memorial International Competition for Young Performers was established, and Green was invited to be a guest lecturer at the first competition in Copenhagen.

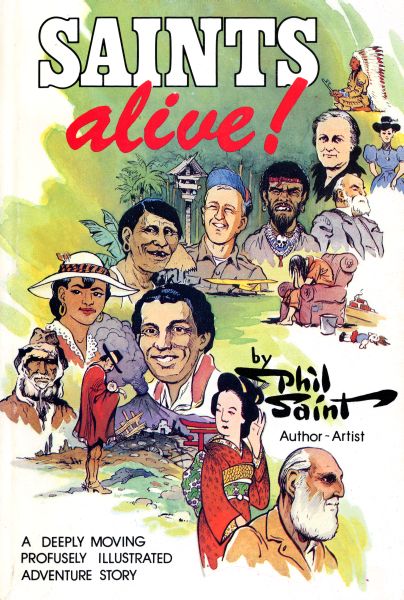

Green’s writing proficiency has produced some of her own books. The Modern Conductor (1961) is now in its fourth edition and already considered a classic. The Dynamic Orchestra was published this year [1987], and Green hopes to add a third volume about her views and experiences as a teacher.

“It’s 50-50,” she says when asked what has given her greatest satisfaction, teaching or performing. She has enthusiastically given her all to both.

“Don’t ever teach an assignment that you yourself are bored with,” is her philosophy of teaching. “When you walk into a classroom, you’re walking onto a stage and the class is your audience.”

Green retired from that stage in 1974. With a little time on her hands, she decided to pursue a lifetime love of painting and earned a fine arts degree from Eastern Michigan University. Now that she’s finally checked that dream off her list, she’s considering slowing down a bit.

But there is that book to write. And pictures to paint. And students still come knocking on her door. “I’ve never been very articulate about my religion,” she says, “but students have always sensed it. They’ve always felt free to come to me with their problems.”

Her advice is both encouraging and practical. “Go after your goal in life, but be prepared to make a living.” Her greater lesson, though, seems to be the vibrant chord of the abundant life that echoes so wonderfully about her.

———-

Elizabeth Green died September 4, 1995. The Papers of Elizabeth Green are housed in the Wheaton College Archives & Special Collections and are available for research.