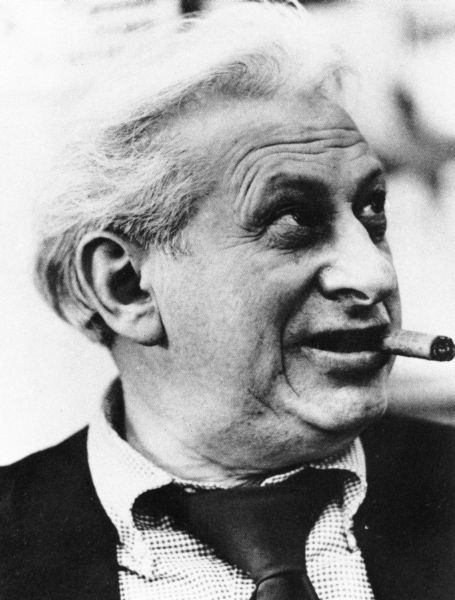

Twenty years ago, the Wheaton Alumni magazine began a series of articles, titled “On My Mind”, in which Wheaton faculty told about their thinking, their research, or their favorite books and people. Professor of Bible Emeritus James Julius Scott, Jr. (who taught at the Wheaton Graduate School from 1977-2000) was featured in the Summer 1994 issue.

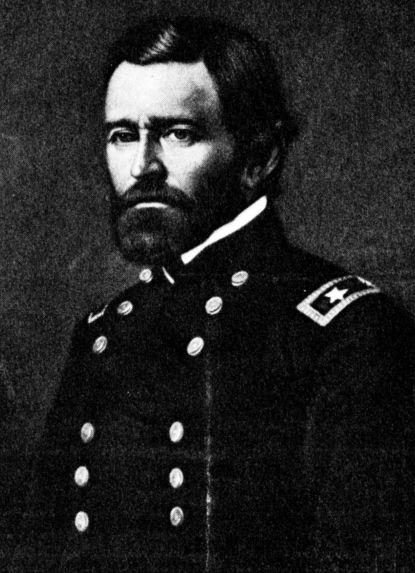

He was already in his forties when first we met. It was only years later that I, his first born, became increasingly aware of his person, manner, and habits which by then were well set. There was one custom, discipline call it what you will–which remains my earliest conscious memory of him, Every morning he was somewhere in the house reading from that black, leather-covered Book.

He was already in his forties when first we met. It was only years later that I, his first born, became increasingly aware of his person, manner, and habits which by then were well set. There was one custom, discipline call it what you will–which remains my earliest conscious memory of him, Every morning he was somewhere in the house reading from that black, leather-covered Book.

He was not a “reader” of a wide range of literature. His business and his farm, but especially his family and church, occupied virtually all of his time. His personal time was spent with that Book. He had not finished college, he had no special training in his particular field, and certainly never had a formal academic course in Bible or theology. But he knew that Book, from Genesis to Revelation.

Although somewhat quiet and unassuming, he was recognized as a leader in his profession, community, and Christian circles. I came to realize, probably often subconsciously, that he approached all of life under the influence of that Book. Underlying principles had seeped into his life and thought from that Book with which he had saturated himself. He ran his home, business, and all other affairs on those principles. It was the basis of his life and a major reason for his success.

The old man gave the “Charge to the Minister” when his eldest son was ordained to the ministry. As far as I know, it was his one formal statement about that Book.

I charge you to preach the Word, to preach the written Word…From my observations as a layman, it seems to me that an alarming number of false prophets have arisen today in our churches and institutions of learning…Beware of false prophets who are teaching and preaching only those things which suit themselves. Guard carefully your relationship to the Scriptures. They are your authority…Remember, Jesus never questioned any…portion of the Scripture, and you can trust his judgment.

I further charge you never to fail to declare the whole counsel of God which is contained in the Scriptures of both the Old and New Testaments, and to avoid the pitfall into which many have fallen, thinking that there are some portions of the Scriptures that are no longer relevant.

There it is, his attitude toward the Bible. It is the Christian’s authority because it was Jesus’ authority. It is the whole Bible to which the Christian is to be committed, and it has continuing relevance. There was something else, between the lines, both written and lived. He loved the Bible because through it he had come to a knowledge of and a life-long, life-controlling commitment to and love for the God of the Bible.

Not long after my ordination, I came to realize that in spite of extensive training, I simply did not know my Bible, at least not in the way Daddy did. Something was missing. Perhaps without being aware of his influence, I set myself upon an intensive program. In spite of the demands of a full-time pastorate, I read through the Bible, consecutively, seven times in the space of two years. Something changed; I began to get the “big picture”; long-familiar parts began to fit into the whole. Saturation and a new foundation for life began. Ideas, teachings, and attitudes became susceptible to reevaluation of a growing familiarity with “the whole counsel of God” (Acts 20:27). To this day the discipline of “reading in big chunks” continues to be an essential, necessary part of my daily training and devotion.

The Bible and the areas of technical study and interpretation of it are the focus of my day-to-day responsibilities at Wheaton. My training focuses on the academic study of the text, languages, literary features, historical world of the Bible, and the development of Christian thought and history which are related to it. I must deal also with controversies, both old and new, which relate to this material. I am thoroughly convinced of the importance and relevance of this study, not only for the specialist, but also for the knowledgeable Christian who must live in the modern world.

I must frankly acknowledge that the irresponsible use of my discipline has too often subverted the spiritual realities which I know lie behind the Bible and Christian experience. Academic biblical and theological studies can easily degenerate into catalysts for skepticism and cynicism. The ill-informed or malicious use the academic study of the Bible to create stumbling blocks, to dampen zeal, quench the Spirit, or destroy faith for the naive, immature believer.

This, I am convinced, is not inevitable. On the contrary, the comprehensive, systematic, evaluative study of the Bible and the Christian faith can and should result in increasing knowledge, maturing faith, strengthening commitment, and developing spiritual discernment. It is an important component of that teaching which trains in righteousness, reproves and disciplines in order that one may be “complete, equipped for every good work” (2 Timothy 3:17). It is the basis for that type of Bible-centered world-and-life view that Wheaton sees as essential for consistent Christian work in each academic discipline and for balanced Christian living.

I keep asking myself, what do I really want for my students? Three things. First, that they will come to know the Bible itself, its content and approach, and especially its “big picture.” I can only help them by pointing out the general overview, the events, people, and major teachings of the Bible. I can then encourage them to seek to fill in that outline with the type of disciplined, consistent reading and study exemplified in my father’s life. Through that, I am convinced, can come the type of life-controlling saturation which was his throughout his pilgrimage.

Secondly, I want my students to love the Bible. Again, I can’t make them do this; but I try to share my love of it with them. We must keep all things in proper perspective; Bible study is not an end in itself. And so, third, more than anything, I want and pray that my students will have a growing knowledge of, commit to, and to be lost in love for the Once of whom the Bible speaks.

———-

The following statement was included at the time of publication: Since 1977, Dr. J. Julius Scott, has taught at the Wheaton College Graduate School. He received a B.A. from Wheaton College in 1956, a B.D. (the equivalent of the M.Div.) from Columbia Theological Seminary in 1959, and a Ph.D. from the University of Manchester in 1969. He is an ordained minister in the Presbyterian Church in America. Prior to teaching at Wheaton, Dr. Scott was a professor of religious studies at Western Kentucky University from 1970 to 1977, and professor of Bible at Belhaven College in Jackson, Mississippi, from 1963 to 1970. Dr. Scott has authored numerous articles, and he is a member of the Society of Biblical Literature, the Evangelical Theological Society, the Institute for Biblical Research, and the Chicago Society for Biblical Research. In the summers of 1984 and 1989 he taught the Wheaton in Israel (Holy Lands) program, and last year (1993) he received the Senior Teacher of the Year award. He has been on sabbatical for the 1993-94 academic year in North Carolina, reading and writing about New Testament theology. Dr. Scott and his wife, Florence, live in Wheaton and have three grown children.