Today, November 18th, is the anniversary of the birth of Louis Daguerre. Born in 1787, Daguerre desired to capture the life and people around him in permanent form. He began to do this with dioramas, which he invented, in the 1820s. By 1826 he had learned how to do this using an early form of photography. Partnering with Joseph Niepce, Daguerre was able to hone the skills he learned in order to greatly speed up the photographic process. Because of this daguerratype photographs became quite desirable and all the rage. This is exhibited several ways within the holdings of the Archives & Special Collections.

Today, November 18th, is the anniversary of the birth of Louis Daguerre. Born in 1787, Daguerre desired to capture the life and people around him in permanent form. He began to do this with dioramas, which he invented, in the 1820s. By 1826 he had learned how to do this using an early form of photography. Partnering with Joseph Niepce, Daguerre was able to hone the skills he learned in order to greatly speed up the photographic process. Because of this daguerratype photographs became quite desirable and all the rage. This is exhibited several ways within the holdings of the Archives & Special Collections.

David Maas wrote in Marching to the Drumbeat of Abolitionism how Civil War soldiers treasured the images they received from loved ones. He said, “Photography was a novelty and soldiers loved to carry tintypes or daguerreotypes in their Bibles. Wheatonite Webster Moses wrote, ‘I still have your picture, which is next to my Bible. Should you have any photographs taken please send me one.’ Luther Hiatt’s letters were full of incessant pleas for his fiancee to have her photograph taken and send it to him. ‘Tira I should have got a picture of myself yesterday taken in Murfreesboro, but I did not have time. If ever I do go to a place where I can get one taken I will do it. I am still looking very anxiously for yours, if you don’t hurry and send it I shall forget how you look.’ When the photograph finally came he was overjoyed: ‘I received your photograph….I was very much pleased to receive it and I kissed it more than once just as I should do if I were to be with you. ‘”

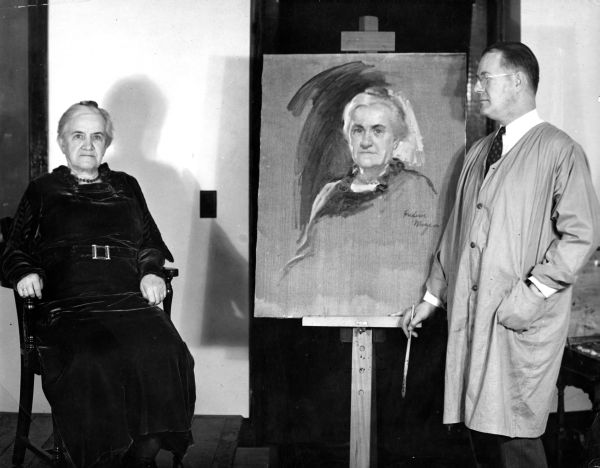

The Jonathan Blanchard letters show several instances of a similar desire to possess these fixed images that Daguerre helped bring to the average person. In 1855 Jonathan Blanchard wrote to his daughter, Mary, who was away at school, asking for a daguerreotype of her. Also, Mary Blanchard’s mother, Catherine Avery Bent wrote to her in 1860 that she was having daguerreotypes taken of her parents’ portraits. Very quickly individuals saw the usefulness of recording information, in this case painted portraits, using the photographic medium.