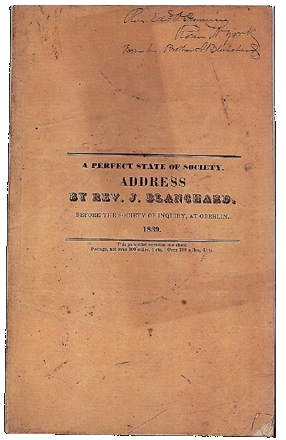

On this 40th anniversary year of the Apollo 14 space mission it is appropriate to consider Wheaton’s relationship to space.

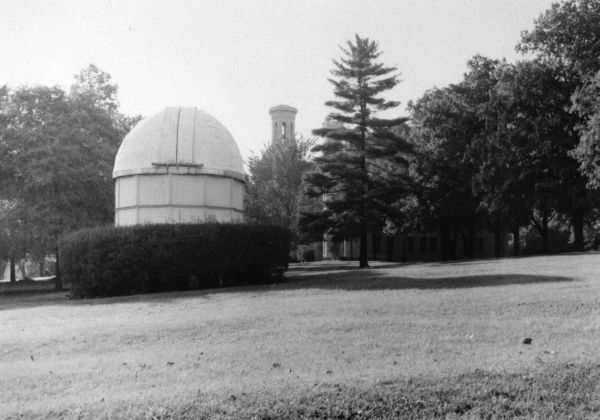

For nearly 70 years a domed observatory, resembling a derelict space capsule fallen to Earth, stood conspicuously on the front lawn of Blanchard Hall. With its telescopic eye poised to the stars, the “Lemon,” as it was nicknamed, informed generations of students about the graceful syncopations of celestial bodies.  Since its 1972 relocation to Camp Honey Rock, the Lemon has been replaced by two successive observatories, both situated atop Wheaton’s science buildings. Since its inception Wheaton College has studied the metaphysical Heaven of the Bible, but the observatory symbolizes its engagement with the physical heavens – and those who’ve set their gaze on that boundless expanse.

Since its 1972 relocation to Camp Honey Rock, the Lemon has been replaced by two successive observatories, both situated atop Wheaton’s science buildings. Since its inception Wheaton College has studied the metaphysical Heaven of the Bible, but the observatory symbolizes its engagement with the physical heavens – and those who’ve set their gaze on that boundless expanse.

Harold Lee Alden, born in Chicago, graduated from Wheaton College in 1912. He acquired his master’s degree from the University of Chicago in 1913. After that he earned his doctorate in astronomy in 1917 from the University of Virginia, where he researched at the McCormick Observatory, using its 26-inch telescope, one of the largest in the world. In 1925 Yale developed a new telescope and shipped it to Johannesburg, South Africa, to observe the clear southern skies. Alden, sent to direct the program, lived there with his family for nearly 20 years, returning to the University of Virginia in 1945, where he served as professor of astronomy and director of the Observatory until retiring in 1960. He died at age 74. As one of 500 deceased men and women of science, including luminaries like Jules Verne and H.G. Wells, Alden was honored to have a crater on the dark side of the Moon named after him.

As a youngster Paul W. Gast, also from Chicago, suffered poor health. Often staying home he read books and magazines like Moody Monthly, from which he learned about Wheaton College. “My ambition has always been research and experimentation,” he wrote on his application. “…And I felt if I was to go into this field it was necessary to go to college.” While at Wheaton, where he was recognized as a top student in chemistry, Gast met his future wife, Joyce, with whom he would parent three children. Graduating in 1952 he pursued advanced education and taught at several universities, notably as Professor of Geology at the University of Minnesota. In 1970 he was hired by NASA as Chief of the Planetary and Earth Sciences Division at the Manned Spacecraft Center in Houston, Texas. As a member of the Lunar Sample Analysis Planning Team, he advised NASA on the disposition of lunar samples brought to Earth by the Apollo missions. For his exemplary service Dr. Gast was awarded NASA’s Distinguished Service Medal, the Geochemical Society’s V.M. Goldschmidt Medal and the American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics Space Science Award. He was president of the Volcanology, Geochemistry and Petrology Section of the American Geochemistry Union, in addition to publishing numerous articles detailing the origin of volcanic rocks, the chemistry of Earth’s upper mantle and geochronology. In 1973 Wheaton College recognized him with its Alumni Service to Society Award. Sadly, Gast had been earlier diagnosed with cancer and died at age 43 in March of that year. “His death,” eulogized geochemist Dr. J. Lawrence Kulp, “is a loss to the nation, to science, to NASA, to his many friends and colleagues, but most deeply to those he loved – his family. May his memory strengthen us, may it enrich our lives and may it turn us to God. That was his desire.”

Grote Reber did not attend Wheaton College, though many of his relatives did. In 1937 Reber, using parts from the University of Chicago and elsewhere, built in his parents’ back yard in downtown Wheaton a radar dish for cosmic radio reception. For ten years he was the only active radio astronomer in the world, listening to the weak but constant static of the solar system. In 1944 he published his discoveries on radio wave transmissions in the Astrophysical Journal. His research paved the way for satellite communications, AM and FM radio bands and cell phones. Reber’s radar dish is now displayed in Green Bank, West Virginia, on the grounds of the National Radio Astronomy Observatory.

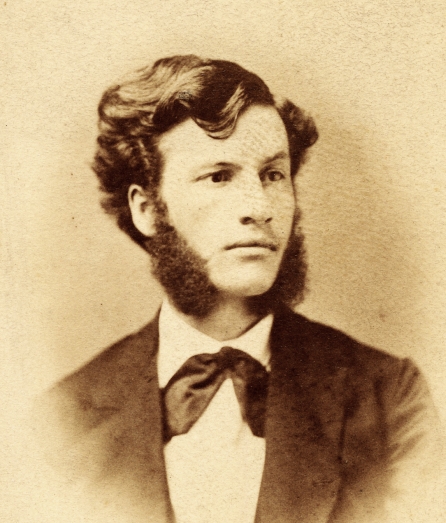

Reber’s mother, a school teacher, stimulated her son’s interest in science with articles written by her former pupil, Edwin Hubble, another explorer of interstellar mysteries. Born in Missouri, Hubble lived for several years in the city of Wheaton, though he did not attend Wheaton College. Graduating from Wheaton High School, he entered the University of Chicago; then, as a Rhodes Scholar, Oxford University. In 1923 he published his paper, “Island Universes,” revealing his discoveries regarding redshifts, the increased wavelengths of radiation emitted by a celestial object. The nebulae farther away, he observed, were receding at the fastest rate, indicating an expanding universe. His seminal work placed him on the cover of Time magazine in 1930. National Geographic cited him as possibly the most important astronomer since Galileo, and Stephen Hawking in A Brief History of Time stated that “Hubble’s discovery that the Universe is expanding was one of the great intellectual revolutions of the 20th Century.” Not only is a middle school in Wheaton named after Hubble, but so is an orbiting telescope, known for its occasional malfunctions as much as for its spectacularly successful functionality. Edwin Hubble died in 1953.

Shannon Lucid was born in Shanghai, China, of parents working with China Inland Mission. When China closed to missionaries, the family moved to Bethany, Oklahoma. From 1960-62 Shannon attended Wheaton College, but departed before completing due to tuition increases, finishing her advanced education at the University of Oklahoma. In 1978 NASA selected her as an astronaut for its Space Shuttle flight crew. Flying multiple missions, Lucid held the record for most hours in orbit of any woman in the world; her record was broken in 2002. She also held the United States single mission flight endurance record on the Russian Space Station Mir. She was been awarded the Congressional Medal of Honor and the Russian Order of Friendship Medal. When asked by reporters if she found God in space, Dr. Lucid replies: “No. God found me years ago. That is your story.”

Some information for this entry is derived from Mary Anne Phemister’s 32 Wheaton Notables, their stories and where they lived.