Andrew Chignell’s article, Whither Wheaton?, appearing in SoMA (The Society of Mutual Autopsy), is proving to be rather provocative, especially as it garners attention for its content as well as its “backstory.” In attempting to provide a guide for the future by looking to Wheaton’s past (more accurately, “near-past”), Chignell reviews the presidency of A. Duane Litfin and his near 17-year tenure. Chignell’s efforts at dissecting Wheaton College’s history is not new, though his particular focus is. Histories and studies of Wheaton College have been written — some official or semi-official, Fire on the Prairie (1950) and Wheaton College: A Heritage Remembered (1984); some very specialized, Edwin Hollatz’s The Development of Literary Societies in Selected Illinois Colleges (1959), Randall Dattoli’s The Wheaton Graduate School (1936-1971): its history and contributions (1980), Lori Witt’s More than a ‘Slaving Wife’ (2001) (examining women at conservative Protestant colleges) and David Swartz’s The Evolution of Creationism at Wheaton College (1999); some focusing upon students and student culture, John Furbay’s Undergraduates in a Group of Evangelical Christian Colleges (1931), John Swanson’s The Graduates of a Midwestern Liberal Arts College Evaluate Their Experiences (1957) and Kevin Cumings’ Student Culture at Wheaton College (1997). These dissertations are also accompanied by numerous masters theses research on Wheaton College. Each title sheds light on what appears to be a monolithic institution; but as Chignell illustrates, Wheaton College exhibits a breadth of perspective involving nuances too often lost on “outsiders.”

Andrew Chignell’s article, Whither Wheaton?, appearing in SoMA (The Society of Mutual Autopsy), is proving to be rather provocative, especially as it garners attention for its content as well as its “backstory.” In attempting to provide a guide for the future by looking to Wheaton’s past (more accurately, “near-past”), Chignell reviews the presidency of A. Duane Litfin and his near 17-year tenure. Chignell’s efforts at dissecting Wheaton College’s history is not new, though his particular focus is. Histories and studies of Wheaton College have been written — some official or semi-official, Fire on the Prairie (1950) and Wheaton College: A Heritage Remembered (1984); some very specialized, Edwin Hollatz’s The Development of Literary Societies in Selected Illinois Colleges (1959), Randall Dattoli’s The Wheaton Graduate School (1936-1971): its history and contributions (1980), Lori Witt’s More than a ‘Slaving Wife’ (2001) (examining women at conservative Protestant colleges) and David Swartz’s The Evolution of Creationism at Wheaton College (1999); some focusing upon students and student culture, John Furbay’s Undergraduates in a Group of Evangelical Christian Colleges (1931), John Swanson’s The Graduates of a Midwestern Liberal Arts College Evaluate Their Experiences (1957) and Kevin Cumings’ Student Culture at Wheaton College (1997). These dissertations are also accompanied by numerous masters theses research on Wheaton College. Each title sheds light on what appears to be a monolithic institution; but as Chignell illustrates, Wheaton College exhibits a breadth of perspective involving nuances too often lost on “outsiders.”

Other historical works helping to reinforce Chignell’s article are found in Wheaton’s Archives & Special Collections. Each of the following are doctoral dissertations, representing research conducted prior to the installation of Litfin as president.

Tom Askew’s 1969 dissertation, Liberal Arts College Encounters Intellectual Change: A Comparative Study of Education at Knox and Wheaton Colleges, 1837-1925 investigates the intellectual life of two colleges led by Jonathan Blanchard, Wheaton’s founder. Blanchard had been Knox’s second (and now relatively little-known) president and Wheaton’s first (though the Illinois Institute had been around for seven years). Askew analyzes how Knox and Wheaton reacted to the tides of intellectual change. His work clearly shows how the president can be a defining and, at times, a polarizing figure, as so with Knox.

Examining Wheaton College and two other colleges, David Larsen’s Evangelical Christian Higher Education, Culture, and Social Conflict: a Niebuhrian Analysis of Three Colleges in the 1960s (1992) discusses Wheaton’s efforts to preserve “elements of the organization’s culture and history in the face of social change” (p. 201). Larsen notes “the place of tradition and the unusual power of the Wheaton presidency for shaping the organizational culture and history” (p. 202). Larsen documents the emergence of public dissent and the growth of underground publications at Wheaton College. The writer also analyzes views on social conflict and justice at Wheaton.

Michael Hamilton, former director of the Pew Young Scholars program that birthed Chignell’s graduate career, wrote The Fundamentalist Harvard: Wheaton College and the Continuing Vitality of American Evangelicalism, 1919-1965 (1994). Hamilton, using Wheaton College as an exemplar, charts its course as the modernist controversy catalyzes the fundamentalist movement, then discusses its emergence and solidification during post-war Evangelicalism as the pinnacle of Evangelical higher education, advancing the principles of faith(ful) integration.

An interesting addition to these dissertations is Citadel Under Siege: The Contested Mission of an Evangelical Christian Liberal Arts College by David Lansdale, a 1990 PhD graduate of Stanford University. Based on archival research and personal interviews (conducted on-site, while supposedly living in his van). An oversimplification, Lansdale’s thesis advances that tensions exist (at any college) between faculty and trustees. This occurs because faculty hold a responsibility to broaden the vision of its students, while trustees must chart and maintain a course. At times these two functions conflict, though not necessarily so. Lansdale’s thesis suggests that Wheaton’s faculty were a liberalizing force and that the trustees would need to counter that force in order to maintain a path of its choosing. This dissertation was circulating on Wheaton’s campus around the time of the presidential search process in the early 1990s.

Chignell’s article tells one aspect of Wheaton’s history over the last twenty years. The works mentioned above further illuminate Chignell’s work and the college’s past. This is certainly not the last word on Wheaton. May Truth ever be sought as scholars engage the historical record.

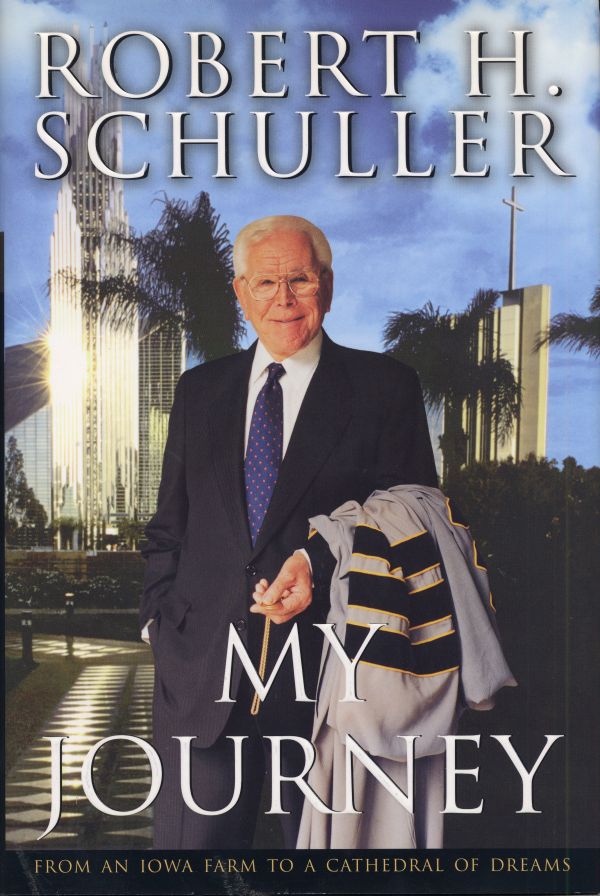

David Iglesias has been one of Wheaton’s alumni who have hit the broader news on occasion, especially more recently. He is known for several things, such as being the inspiration for Tom Cruise’s character Lt. Daniel Kaffee in A Few Good Men, a writer, and a United States Attorney (later fired in a political firestorm), however poet has never been listed among his credits. Before this.

David Iglesias has been one of Wheaton’s alumni who have hit the broader news on occasion, especially more recently. He is known for several things, such as being the inspiration for Tom Cruise’s character Lt. Daniel Kaffee in A Few Good Men, a writer, and a United States Attorney (later fired in a political firestorm), however poet has never been listed among his credits. Before this.Squatting Buddha and