Wheaton College is widely recognized for its endeavor to integrate faith and learning, so it is somewhat surprising to discover that there was a moment when its administration stoutly resisted the implementation of a theater program. It may also come as a surprise for some to learn that another Christian liberal arts college, Bob Jones University, pursued drama as a valid educational discipline decades before Wheaton.

Bob Jones College (now University) was founded in 1927 in College Point, Florida, by Methodist revivalist Dr. Bob Jones Sr. He determined that this institution defy the mockery of the day. “This college,” he said, “was founded [to] neutralize in this country the idea that if you are conservative and believe the Bible, that you are a sort of fanatic, or you’re lopsided or something. Some people – worldly, highbrowed, snooty people – think that if you’re a Christian, you’re queer…So we wanted to build a college that would neutralize in the minds of the public the idea that culture does not go hand in hand with the old-time conservative, Christian approach, and so we started off on that basis.”

Bob Jones College (now University) was founded in 1927 in College Point, Florida, by Methodist revivalist Dr. Bob Jones Sr. He determined that this institution defy the mockery of the day. “This college,” he said, “was founded [to] neutralize in this country the idea that if you are conservative and believe the Bible, that you are a sort of fanatic, or you’re lopsided or something. Some people – worldly, highbrowed, snooty people – think that if you’re a Christian, you’re queer…So we wanted to build a college that would neutralize in the minds of the public the idea that culture does not go hand in hand with the old-time conservative, Christian approach, and so we started off on that basis.”

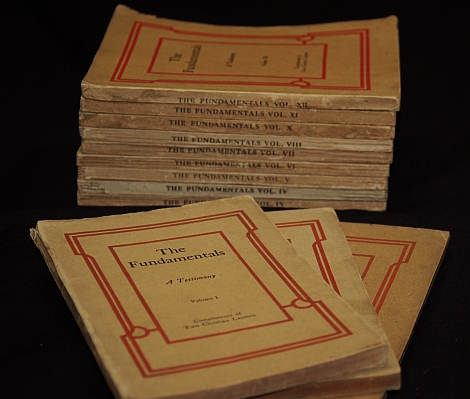

But the appearance of Bob Jones College on the Christian educational scene was not welcomed by all within the conservative community. Most notably, J. Oliver Buswell, third president of Wheaton College, publicly objected, stating, “One [orthodox school] is enough. We ought to stay by that.” He added that, “Wheaton was doing everything that needed to be done.” Jones ignored Buswell and forged ahead. With its student body expanding amid the modernist/fundamentalist controversies of the 30s and 40s, the college moved from Florida to Cleveland, Tennessee, and finally to its present location in Greenville, South Carolina.

But the appearance of Bob Jones College on the Christian educational scene was not welcomed by all within the conservative community. Most notably, J. Oliver Buswell, third president of Wheaton College, publicly objected, stating, “One [orthodox school] is enough. We ought to stay by that.” He added that, “Wheaton was doing everything that needed to be done.” Jones ignored Buswell and forged ahead. With its student body expanding amid the modernist/fundamentalist controversies of the 30s and 40s, the college moved from Florida to Cleveland, Tennessee, and finally to its present location in Greenville, South Carolina.

Occasionally Wheaton and Bob Jones College attempted to cooperate, but these efforts often failed. For instance, in 1929 Buswell and other Christian educators tried to convince Jones to join their fight against educational standardization. Jones resisted, stating that he wanted to cooperate with religious educators; beside that, he wanted academic standardization rather than accreditation. Just a few years later Buswell and his colleagues reversed their position, organizing an accrediting organization for religious schools. Jones refused to join, believing that any such association ran counter to the goals of Bob Jones College and its board. So Jones paid a dear price: BJC was stigmatized as anti-intellectual and publicly attacked by Buswell because it remained unaffiliated with the association he headed.

In 1940 tension between the two institutions exacerbated when the Bob Jones College Classic Players, the only college-based repertory in the nation, performed Shakespeare and Greek tragedy. Of course, BJC received pointed criticism from its Fundamentalist constituency.  However, John R. Rice, editor of The Sword of the Lord, located in Wheaton, Illinois, defended the program, stating that “Shakespeare is great literature.” As with other subjects pertaining to the human experience, it was worthy of study. Again, the sharpest criticism was launched by Buswell, who had resisted drama at Wheaton College until his dismissal from its presidency in 1940, though students favored theatrical studies. Reviewing a 1949 sermon by Dr. Bob, Sr., Buswell, now serving as president of Shelton Bible College in New York, inquired: “…Let me ask you a question or two. Your own educational program is reeking with theatricals and grand opera, which lead young people, as I know, and as you ought to know, into a worldly life of sin.” John R. Rice published a three-page rebuttal in The Sword of the Lord, declaring that Buswell’s assertion was “utterly untrue.” In the years after Buswell left Wheaton, some classes were known to perform at least one short play, skit or pageant per week. Dr. Ed Hollatz, who completed his undergraduate degree at BJU and later served as professor of Speech and Communication at Wheaton, directed in 1966 Wheaton’s first “official” drama, Macbeth, inaugurating a series of successfully produced performances at Arena Theater. Stagings by others include Tartuffe, Medea, Murder in the Cathedral, The Crucible, Waiting for Godot and many more.

However, John R. Rice, editor of The Sword of the Lord, located in Wheaton, Illinois, defended the program, stating that “Shakespeare is great literature.” As with other subjects pertaining to the human experience, it was worthy of study. Again, the sharpest criticism was launched by Buswell, who had resisted drama at Wheaton College until his dismissal from its presidency in 1940, though students favored theatrical studies. Reviewing a 1949 sermon by Dr. Bob, Sr., Buswell, now serving as president of Shelton Bible College in New York, inquired: “…Let me ask you a question or two. Your own educational program is reeking with theatricals and grand opera, which lead young people, as I know, and as you ought to know, into a worldly life of sin.” John R. Rice published a three-page rebuttal in The Sword of the Lord, declaring that Buswell’s assertion was “utterly untrue.” In the years after Buswell left Wheaton, some classes were known to perform at least one short play, skit or pageant per week. Dr. Ed Hollatz, who completed his undergraduate degree at BJU and later served as professor of Speech and Communication at Wheaton, directed in 1966 Wheaton’s first “official” drama, Macbeth, inaugurating a series of successfully produced performances at Arena Theater. Stagings by others include Tartuffe, Medea, Murder in the Cathedral, The Crucible, Waiting for Godot and many more.

Since those early, steamy days, both Wheaton and Bob Jones University have enjoyed endless banquets of cultural offerings. Dr. Bob Jones, Jr., second president of the university, was an accomplished Shakespearean actor, approached by Hollywood and Broadway (refusing both), in addition to founding the largest Renaissance art collection in the western hemisphere. Similarly, Wheaton College, west of Chicago, boasts a world-renowned curriculum showcasing music, art, theater and writing, in addition to maintaining attractive, oft-visited campus museums featuring archaeological artifacts, British literature and American evangelism.

Other notable Wheaton College faculty who attended BJU include Robert E. Webber, late professor of Theology, Joseph McClatchey, late professor of English and Rolland Hein, retired professor of English.

Correspondence pertaining to the ideological complaints of Bob Jones, both Sr. and Jr., against the National Association of Evangelicals (SC-113) is maintained in Special Collections at Wheaton College.

(Much of the material for this entry is derived from Daniel L. Turner’s Standing Without Apology: The History of Bob Jones University, 2001)

The deportment of the sexes towards each other will he particularly regarded by the Faculty, and any student whose conduct shall be, in the judgment of the Faculty, either foolish or improper, will be promptly separated from the institution, if admonition fails to correct it. In short everything is forbidden which will hinder, and everything required, which, we think, will help students in the great object for which they assemble here, which is improvement of mind, morals and heart.