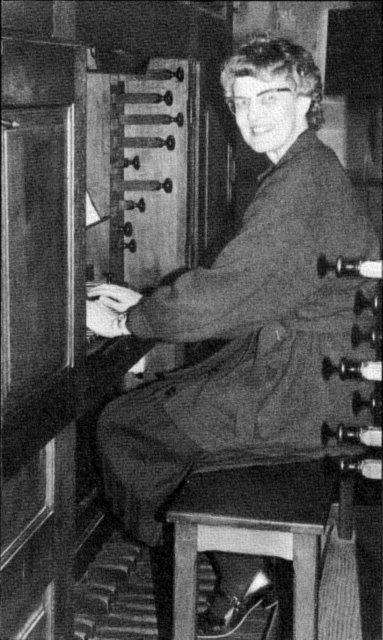

The following article about Conservatory Professor Gladys Christensen ’49 was featured in the Wheaton College Alumni Magazine in June 1987 and is transcribed below.

An Instrument of Service

An Instrument of Service

by Sue Miller ’82

I can remember as a very young child going up and trying to touch an organ, and the organist, of course, shooed me away very quickly,” recalls Gladys Christensen ’49, professor of music at the Wheaton Conservatory of Music.

In spite of her initial brief encounter with the instrument, Gladys went on to pursue organ study in high school and at Wheaton, eventually earning a master of music degree from Northwestern University. She returned to Wheaton in 1954 for a two-year part-time teaching position. At the end of that time, the Conservatory asked her to join the faculty full time.

After 33 years of teaching organ at Wheaton, Gladys knows what works with students. “I think a good teacher is one who inspires a student to do very well and inspires in him or her a love of the great organ literature, as well as the experience of church service playing.” She enjoys teaching a student who will search out material and research the background of the literature. Her goal is to teach students to be independent of her so they can select a piece of music, register it and play it well. “That is the most exciting kind of teaching because I am bringing out something in that student which doesn’t come easily. It’s a developmental process.”

In addition to teaching solo performance, Gladys has the responsibility of instructing her students in the art of church service playing. “Accompanying is the major part of the organist’s work, rather than solo playing…The accompanimental role is a very tricky one because you are dealing with the individuality of the soloist or the choir. You must enhance and support without overpowering.” Teaching this type of sensitivity is difficult for two reasons: There is no choir, soloist or congregation with which to practice, and Gladys can seldom observe her students on location since service.

Church accompaniment has been a vital part of Gladys’ musical career for over 30 years. During the past school year she has been interim organist for several churches. To enjoy service playing, an organist must develop a philosophy of ministry because “what the organist enjoys playing the most is not what he or she is called upon to do in church. Sometimes you feel a little resistant to the number of hours you have to put into preparing music that is somebody else’s choice. You are imprisoned by another’s taste. I was taught that the church organist is very self-effacing…Flexibility and adaptability are two qualities of a good church organist.”

In spite of the inherent difficulties in service playing, Gladys affirms there is satisfaction in knowing that her playing is an inspiration to people in t worship service. “To lead in worship is a privilege. It’s a two-way street: we worship together.”

Last spring, Gladys took a sabbatical in Europe in order to practice organ technique and to study the literature relevant to the instrument for which it was written. She studied with Lionel Rogg, professor of organ at the Conservatoire de Musique in Geneva, Switzerland. Gladys wanted to become proficient in a technique for the tracker or mechanical action organ. Tracker organs, as opposed to electro-pneumatic organs, were once the only way organs were built, and they have regained the attention in organists in recent years. “With a mechanical action instrument, the organist is actually controlling the speech of the pipe…You do feel immediacy with the tracker organ, which makes it a more responsive action to the artist.”

Another benefit of Professor Christensen’s sabbatical was the opportunity to become acquainted with the French and German instruments for which the literature was composed. “The instruments in their own surrounding reveal the literature,” explains Gladys. When her students are studying, for instance, a piece written in Germany 200 years ago, Gladys can embellish the lesson with her own experience of having played the original (or restored) organ in the composer’s actual church–or one close to it. “More than for any other instrument, the literature of the organ is directly tied to the instrument of the time and country for which it was composed.”

The dual role of scholar and teacher is what keeps Professor Christensen fresh in the classroom. Her joy in the instrument spreads to all those around her.

———-

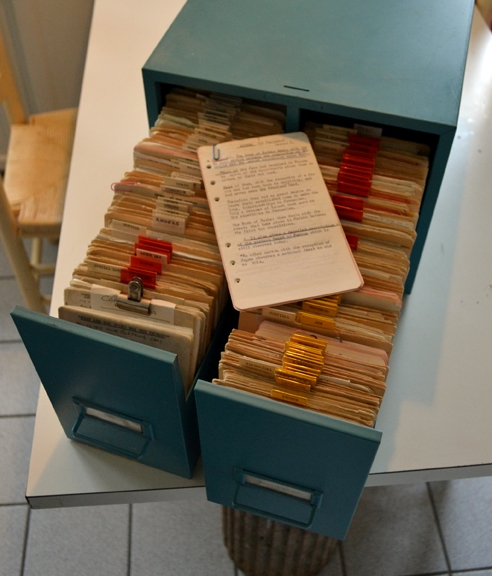

Gladys Christensen died on November 8, 2011. She served as professor of organ and harpsichord in Wheaton’s Conservatory of Music from 1954 to 1988. Gladys was very well known in the community and was very active in the American Guild of Organists having memberships with the Chicago, North Shore, and Fox Valley Chapters over many years. She was a graduate of the Wheaton College Class of 1949, and Professor of Music Emerita at Wheaton College at the time of her death. During her teaching years at Wheaton, she also taught Church Music, Music Theory, Organ Literature and Pedagogy. She attended many masterclasses throughout the USA and Europe, and studied organ with many of the great teachers of her time. She was well-loved and well-respected throughout many musical circles in Chicagoland. Gladys had asked that memorial gifts be made to the Lester Wheeler Groom Organ Recital Endowment which funds guest organ concerts, as well as student scholarships at Wheaton College. She established the Foundation years ago with the intention that it will continue to support organ music at Wheaton.