At first glance, Wheaton College in Wheaton, Illinois, and Fermilab National Accelerator Laboratory in Batavia, Illinois, share few points of commonality; but a closer examination reveals otherwise.

Wheaton College (est. 1860) and Fermilab (est. 1967) were intentionally situated on the largely undeveloped prairie about thirty miles west of Chicago for convenient access by cross-country traffic.

Both institutions employed talented veterans of the classified Manhattan Project, which eventually ended WW II. Dr. Robert Rathbun Wilson (1914-2000), Fermilab’s first director and guiding visionary, served as the head of R (Research) Division at Los Alamos, New Mexico, under the supervision of Dr. J. Robert Oppenheimer, the “father of the atomic bomb.” Similarly, Dr. Roger Voskuyl (1910-2005), professor of Chemistry at Wheaton College and later president of Westmont College in Santa Barbara, California, served as a group leader for the top-secret mission.

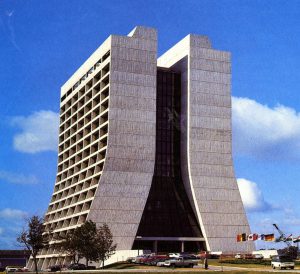

Administrative and academic activities for both campuses revolve around iconic loci featured on signage and letterhead. Fermilab’s Wilson Hall, aesthetically influenced by the gifted architect Robert R. Wilson, dominates the landscape at sixteen stories. The upward sweep of its outer walls, somewhat resembling praying hands, purposely evokes the Beauvais Cathedral in France, the most daring Gothic undertaking of the 13th-century.

Wheaton College’s neo-Gothic main building, Blanchard Hall, recalls structures admired by founder and first president Jonathan Blanchard during a European journey.

While Jonathan Blanchard was a rock-ribbed Yankee who protected escaped slaves via the Underground Railroad, Robert Wilson was a proud descendant of abolitionist John G. Fee, founder of Berea College, a school for blacks and whites in pre-Civil War Kentucky. Wilson also actively recruited people of color to work at Fermilab during the Civil Rights Movement.

Fermilab’s staggeringly complex machinery, particularly DUNE (Deep Underground Neutrino Experiment), is extensively networked beneath the farmland of Batavia, while the sandstone blocks used to construct Blanchard Hall were cut from a quarry in Batavia.

Both institutions boast pretty good cafeterias.

A herd of buffalo, brought by Wilson to recall his beloved childhood home in Wyoming, graze the high grasses on a ranch at Fermilab, while a gaggle of haughty geese strut freely through the manicured acreage of Wheaton College.

Fermilab educates students, scientists and engineers from all over the world. Likewise, globally minded Wheaton College prepares international missionaries, teachers, pastors and other workers, fulfilling Christ’s Great Commission: “Go therefore and make disciples of all nations, baptizing them in the name of the Father and of the Son and of the Holy Spirit, teaching them to observe all that I have commanded you. And behold, I am with you always, to the end of the age” (Matthew 28:19-20).

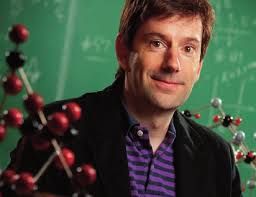

As Dr. Leon Lederman, the Nobel Prize winning second director of Fermilab, observes, the U.S. Department of Energy research facility investigates with perpetual wonder and perplexity the subatomic conundrums posed by “inner space, outer space, and the time before time.” Exploring multidimensionality from a literary vantage, Wheaton College displays a wardrobe owned by British author C.S. Lewis, which modeled the magical doorway into Narnia. In addition, the Christian liberal arts college archives the papers of Madeleine L’Engle, who wrote A Wrinkle in Time, about a perilous trek through the centuries. In fact, her award-winning science fantasies were inspired by papers published by theoretical physicists Albert Einstein, Max Planck and Niels Bohr.

And despite the efforts of the finest minds and the most sophisticated instrumentality, the comprehensive “theory of everything,” the invisible energy field that holds the universe intact, remains frustratingly elusive. “The universe is the answer,” laments Lederman in The God Particle (1993), “but damned if we know the question.”

If one imagines an anthropomorphized Wilson Hall crying out the plaintive inquiries of a puzzled quantum physicist to the starry cosmos, then Blanchard Hall, standing only ten miles away, simply responds to that plea with Hebrews 1:3, “[Jesus] is the radiance of the glory of God and the exact imprint of his nature, and he upholds the universe by the word of his power.”

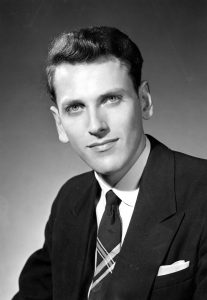

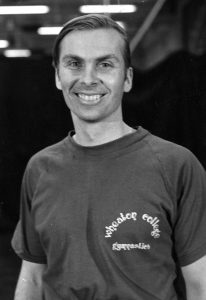

Like any good soldier, Dr. George “Bud” Williams (1942-2019) performed all assigned tasks with exactitude and energy. He studied at Penn State and was accepted (but did not attend) Yale University. Excelling in gymnastics, he served as Instructor in Physical Education and Coach at West Point Military Academy. He commanded an ROTC battalion, and taught various aspects of health and athletics at Wheaton College, stressing the necessity for nutrition, hygiene and spiritual renewal.

Like any good soldier, Dr. George “Bud” Williams (1942-2019) performed all assigned tasks with exactitude and energy. He studied at Penn State and was accepted (but did not attend) Yale University. Excelling in gymnastics, he served as Instructor in Physical Education and Coach at West Point Military Academy. He commanded an ROTC battalion, and taught various aspects of health and athletics at Wheaton College, stressing the necessity for nutrition, hygiene and spiritual renewal. Bud was committed to the formation of a hardy but sensitive moral character stabilized and nourished by the Spirit of God, and constantly sought resources that would inculcate this principle to his classes, indoors or out. He knew that when the man or woman securely rooted in Christ passed from the scene, a lingering force of integrity, a wide-ranging, life-giving testimony should remain, ever attracting a fallen humanity to the risen Savior.

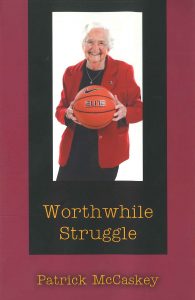

Bud was committed to the formation of a hardy but sensitive moral character stabilized and nourished by the Spirit of God, and constantly sought resources that would inculcate this principle to his classes, indoors or out. He knew that when the man or woman securely rooted in Christ passed from the scene, a lingering force of integrity, a wide-ranging, life-giving testimony should remain, ever attracting a fallen humanity to the risen Savior. Worthwhile Struggle by Patrick McCaskey features a grab bag of inspirational stories woven with tales of exemplary athletes. Included are McCaskey’s “10 Commandments of Football,” based on his upbringing in the Halas-McCaskey family with the Chicago Bears. Deeply involved with faith-based initiatives and charitable causes, McCaskey is active in promoting strong principles and honest gamesmanship.

Worthwhile Struggle by Patrick McCaskey features a grab bag of inspirational stories woven with tales of exemplary athletes. Included are McCaskey’s “10 Commandments of Football,” based on his upbringing in the Halas-McCaskey family with the Chicago Bears. Deeply involved with faith-based initiatives and charitable causes, McCaskey is active in promoting strong principles and honest gamesmanship. Betty Smartt Carter, essayist and novelist, relates her student years at Wheaton College in her poignant, brutally honest memoir, Home is Always the Place You Just Left (2003).

Betty Smartt Carter, essayist and novelist, relates her student years at Wheaton College in her poignant, brutally honest memoir, Home is Always the Place You Just Left (2003).

E.E. Shelhamer (1869-1947), prominent Methodist evangelist and author, writes of his early years at Wheaton College in Sixty Years of Thorns and Roses:

E.E. Shelhamer (1869-1947), prominent Methodist evangelist and author, writes of his early years at Wheaton College in Sixty Years of Thorns and Roses:

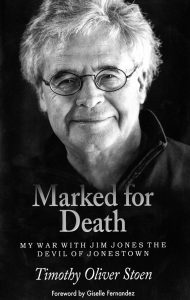

On June 26, 2000, he resumed his career as a California prosecuting attorney. He was nominated in 2010 to the California District Attorneys Association as Prosecutor of the Year, and in 2014 was honored as one of the five top wildlife prosecutors in the state. Stoen tells his remarkable story in Marked for Death: My War with Jim Jones the Devil of Jonestown (2015).

On June 26, 2000, he resumed his career as a California prosecuting attorney. He was nominated in 2010 to the California District Attorneys Association as Prosecutor of the Year, and in 2014 was honored as one of the five top wildlife prosecutors in the state. Stoen tells his remarkable story in Marked for Death: My War with Jim Jones the Devil of Jonestown (2015).