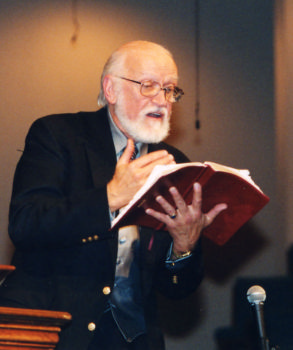

As the final section of his autobiography, Life is Mostly Edges (2008), Dr. Calvin Miller, pastor, poet and professor, asks the reader what he or she would do differently, if life could be repeated. At age 72 he answers the question for himself:

As the final section of his autobiography, Life is Mostly Edges (2008), Dr. Calvin Miller, pastor, poet and professor, asks the reader what he or she would do differently, if life could be repeated. At age 72 he answers the question for himself:

1. I would put more emphasis on being a better husband and father. To the church or the university I would whip out a lot more noes, and a lot more yesses to my family. I would eradicate almost all of the “Daddy’s-too-busies,” and the “later, darlings,” from my vocabulary. If the church suddenly came up with a critical meeting on circus night, I’d go to the circus.

2. I’d celebrate my mother in her presence. She was a simple woman whose humility kept her from seeing just how great she was. This adherence to her modesty I would shatter with the sledgehammer of praise. How would I do this?…I would write her a check for all the times she struggled to keep the family together…I would walk her to work in the morning and carry her lunch, and meet her when the day was over to tell her that I loved her…If anyone had maltreated her, I would get their address and visit them with an axe at midnight…For every time when I had made life hard for her, I would do seven years of penance…I would be there all the more for the woman who was always there for me.

3. I’d build a monument on Golgotha. I would build myself a replica of Golgotha, an Everest of Calvary, so high that the empty cross at its summit would be hidden by the mist of sheer altitude. I would keep a shrine at the top of my giant Calvary, with no sugary idols where the dying was done. I’d have no icons there, for the living Jesus who has been the central icon of my life would meet me there. When he came at sunrise, I would be there with the bread. And when he came at dusk, I would be there with the wine. And I would reverse my prayer life. I wouldn’t talk to him so much; I would listen more. I still wonder after a lifetime of chatty prayers, if I had not been so noisy in his presence, would he have told me more of his giant heart?

4. I’d babysit. Could I pass this way again I would take seriously a little girl in our church with whom I was hugging and laughing and having a great time, when suddenly she stopped my teasing her and asked point-blank, “Dr. Miller, do you ever do babysitting?” I told her I was too busy. But if I had to do all over again, I’d do more babysitting. In general I’d take more time for children and perhaps less for deacons.

5. What am I doing to be sure that I am a good steward of the years I have left? First, I am determined that this question will not drive me. One thing I do not want for the years I have left is to be so preoccupied with an agenda that I will not have time for anything but the drive…Such a tight little squinting of the eyes gobbles up our peripheral vision. It steals the panorama of what we might have seen if we had laid down some of our busy agenda and looked around a bit.

6. I’ll stop looking ahead and look around more. Looking around more will be my focus in my final years. I will smell the roses of Versailles and count the scent as sweet as those on the altar of the church. I will bypass a great many Christian novels and go on reading Pulitzer Prize winners just as I have always done. And I will not be so bent on my writing that I have no time to look around. I will not type my manuscripted way into the grave, staying so busy that I cannot take a walk with my wife, work the New York Times acrostic, go to a movie, or see a play…Looking around more means walking in a good direction but with an unhurried step. I would like to begin each day with God and then, coffee cup in hand, go out into the world. I don’t want to try and dissect it. I don’t want to figure it out. I just want to walk about in it. I also want to celebrate the simple things.

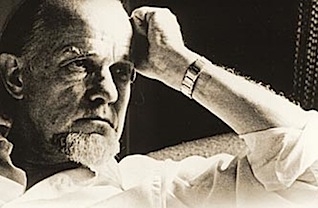

Miller, formerly pastor of Westside Baptist Church in Omaha, Nebraska, is currently Professor of Preaching and Pastoral Ministry at Samford University’s Beeson Divinity School. He has written over 40 books, including novels and poetry, notably The Singer and The Symphony trilogies. His papers (SC-24), comprising manuscripts, correspondence and watercolor artwork, are archived at Wheaton College (IL) Special Collections. He has lectured at Wheaton College on several occasions.