Malcolm Muggeridge’s first play was Expense of Spirit, which according to Muggeridge biographer, Ian Hunter, was “a rather tepid play.” The play was a veiled retelling of his father’s successful 1929 election as a Labour M.P. (member of Parliament). Hunter called it “a rather cruel caricature” of H. T. Muggeridge.

Malcolm Muggeridge’s first play was Expense of Spirit, which according to Muggeridge biographer, Ian Hunter, was “a rather tepid play.” The play was a veiled retelling of his father’s successful 1929 election as a Labour M.P. (member of Parliament). Hunter called it “a rather cruel caricature” of H. T. Muggeridge.

Muggeridge’s second play, Three Flats, was one that actually saw the stage and received some attention.

Three Flats, on the other hand, is a curious play that allows the audience to look into the lives of the occupants of three high-rise flats. On the bottom floor live two single schoolteachers quietly desperate to get married; one sublimates her yearning into her work and is miserable; the other yields to it in promiscuity and is content. Then a middle-aged couple, Mr. and Mrs. Mason, whose marriage of twenty years has become a worn husk in which the seed has shriveled; finally, on the top floor, Maeve Scott, a naive young woman of what, at one time, would have been called “liberated” views, unmarried and living with a “struggling, unsuccessful litterateur” named Dennis Rhys who, undoubtedly speaking for Muggeridge, wonders to himself: “Why does one write?–a silly trade. Why isn’t it enough to live; to feel things–why must one always be grinding them out in words? And yet it seems the only thing to do.”

What is the unity, the play asks, in these three lives? What is it that makes such people, and countless others like them living in flats everywhere, carry on from day to day? Muggeridge provides insufficient scope to answer such questions and seems content just to raise them. There is a point to it all, he seems to be saying, but not yet sure what it is.

The play was first performed at the Prince of Wales Theatre on February 15, 1931. Its frankness offended his family and some critics. His father came to opening night, but still voiced disapproval of what he considered a preoccupation with sex. Kitty’s aunt, Beatrice Webb, disliked it intensely; she said she was “shocked,” not so much for herself, but for those in the audience whose sensibilities she presumed to be less robust than her own.

Even this early and insignificant play has an odd prophetic quality about it; in one sense it is an examination of the effects of high-rise living, then comparatively rare, on individual morality. The play attracted extensive notices, most of them favorable. One critic said, “There was plenty of truth in the offing, but the bane of the contemporary theatre, Dr. Freud, would keep breaking in.”

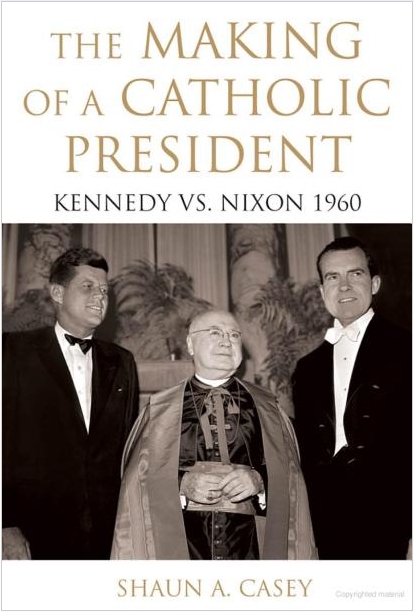

Kennedy’s run for the U.S. presidency brought to the fore many concerns about the role of religion in public life. Grave were the concerns of some that Kennedy, as a Catholic, would have divided allegiances and may swear more allegiance to the Pope (viewed as a foreign and religious power) than the Constitution.

Kennedy’s run for the U.S. presidency brought to the fore many concerns about the role of religion in public life. Grave were the concerns of some that Kennedy, as a Catholic, would have divided allegiances and may swear more allegiance to the Pope (viewed as a foreign and religious power) than the Constitution.