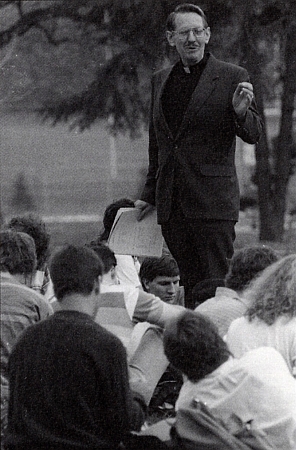

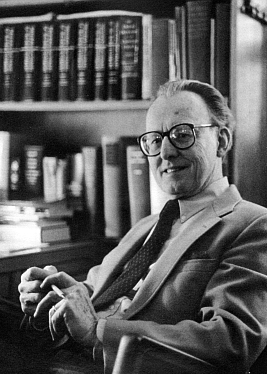

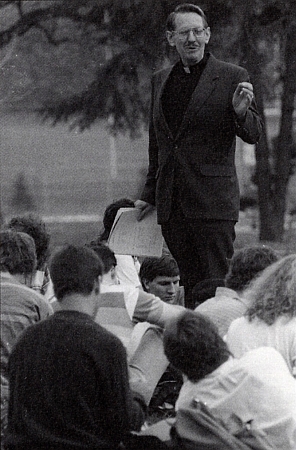

Beginning in the mid-1970s when Art Rupprecht and Jerry Hawthorne joined a group of their very interesting and interested Greek students late on Friday afternoons in the Stupe. The week’s classes were over and it was time to relax with a free cup of coffee — they arrived just at closing time when the staff were about to throw the remaining coffee down the drain. It was theirs for the taking. Faculty and students spent time thinking through some theological issues, talking about baseball or fishing, or discussing some difficult Greek passage, telling a few jokes, and generally enjoying each others company and insights. Soon others wanted to join. So it became a weekly feature, but it was too large and often too raucous to continue meeting in a corner booth of the Stupe.

Beginning in the mid-1970s when Art Rupprecht and Jerry Hawthorne joined a group of their very interesting and interested Greek students late on Friday afternoons in the Stupe. The week’s classes were over and it was time to relax with a free cup of coffee — they arrived just at closing time when the staff were about to throw the remaining coffee down the drain. It was theirs for the taking. Faculty and students spent time thinking through some theological issues, talking about baseball or fishing, or discussing some difficult Greek passage, telling a few jokes, and generally enjoying each others company and insights. Soon others wanted to join. So it became a weekly feature, but it was too large and often too raucous to continue meeting in a corner booth of the Stupe.

Just as concerns over a meeting place arose a new chapel schedule was implemented with chapel to be held weekly on Mondays, Tuesdays, Thursdays and Fridays — leaving Wednesday at 10:30 free when faculty and students had no officially scheduled meetings. So Wednesday became the new day. Now all that was needed was a place. John Ortberg, speaking for his housemates, offered Windsor House as the newly designated place of meeting. It was agreed that faculty would provide the donuts and the Windsor men would provide the coffee. Occasionally one of the faculty would fudge a little on the donut buying, for one of them was caught slipping across to Windsor house early, to heat up an Aldi’s day-old coffee cake for the coffee hour.

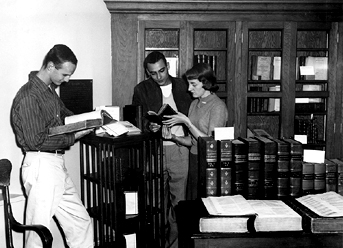

Eventually these Windsor men graduated, but the new men assigned to that house wanted us to continue, which the faculty were only too happy to do. Windsor House, which was adjacent to Buswell Library, continued to be a place of meeting for students from all parts of the world, faculty from all disciplines — a great amalgam of students and faculty. Discussions were lively and sometimes even heated, but always argued with passion, if not always with reason. Everyone present could not help learning something he (all men in those days) had not known before–those were great times together.

When Windsor House was torn down the group was invited to join the men in Kay House, so that this tradition could continue. By the time that particular Kay House group of men were ready to move on via graduation to their higher calling, the new “pharaoh knew not Joseph.” So no successive invitation was extended from that house. When that moment of desperation came, however, many of our student friends were awarded Hidden House as their next year’s domicile, and with one voice they beckoned us to come and join them at their home each Wednesday morning as usual. The tradition kept going and growing. This pleasurable and profitable welcome break from the routine bustle of academic life continued unabated for more than a decade.

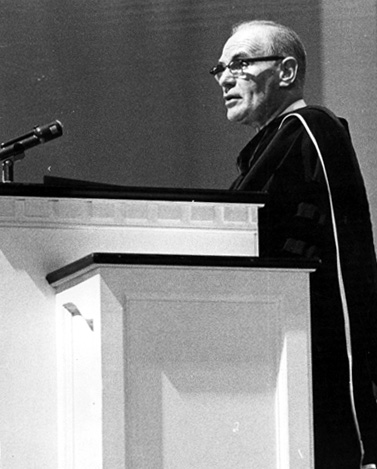

As change is always inevitable, the chapel schedule changed again. The new schedule had it fall on Monday, Wednesday and Friday. Not wishing to flaunt chapel, nor to encourage undesirable behavior on the students part, the majority of the faculty regulars decided that all who wished could come to Jerry Hawthorne’s office (on the second floor of Wyngarden Health Center) at the traditionally designated time. As many as 15-18 professors from the departments of literature, language, philosophy, psychology, sociology, history, communication and the sciences crammed into that small office for the weekly repast of coffee and donuts. Here the late and beloved Dr. Joe McClatchey delighted to come as long as he was alive; it was he who dubbed this place and this congregation, “Jerry’s Pub,” a name it still holds, although the infamous “Jerry” is now retired, and the Pub presently meets on Tuesdays and Thursdays in Art Rupprecht’s office.

As change is always inevitable, the chapel schedule changed again. The new schedule had it fall on Monday, Wednesday and Friday. Not wishing to flaunt chapel, nor to encourage undesirable behavior on the students part, the majority of the faculty regulars decided that all who wished could come to Jerry Hawthorne’s office (on the second floor of Wyngarden Health Center) at the traditionally designated time. As many as 15-18 professors from the departments of literature, language, philosophy, psychology, sociology, history, communication and the sciences crammed into that small office for the weekly repast of coffee and donuts. Here the late and beloved Dr. Joe McClatchey delighted to come as long as he was alive; it was he who dubbed this place and this congregation, “Jerry’s Pub,” a name it still holds, although the infamous “Jerry” is now retired, and the Pub presently meets on Tuesdays and Thursdays in Art Rupprecht’s office.

The fact that we met on Wednesdays during chapel was information that could not be kept secret. Eventually it reached the ears of the Board of Trustees. They asked the President to see if this were true or simply rumor. If true he was charged to ask this group to cease and desist. When the President learned of the long history of this group and reported this to the Trustees and that it was not a subversive group intending to undermine chapel, the Board graciously gave the group permission to continue on Wednesdays at Chapel time, but only until Hawthorne retired. Hence, the new schedule.

Although this group never attained the recognition and reputation of C. S. Lewis’ “Inklings,” it nevertheless served the same purpose. From among those students who regularly attended “the Pub,” not a few of them have gone on to help, under God, to make this world a better place in which to live. Many of them have distinguished themselves as doctors, missionaries, pastors, artists, university professors, college presidents, public school teachers, leaders in development programs, clinical psychologists, and the list goes on and on.

I recently drove past a church and its sign said “Casual Worship, 9:30 a.m.” I know what they meant as they placed this message on their sign, but it also can communicate something completely different. The sign could have some unintended consequences. Evangelicalism is exhibiting signs of broad differences of opinion in the area of worship. As one segment goes further into minimizing worship styles to appeal to a wider unchurched public another segment seeks to retain or heighten the liturgy that has been a part of the church for over a millennia.

I recently drove past a church and its sign said “Casual Worship, 9:30 a.m.” I know what they meant as they placed this message on their sign, but it also can communicate something completely different. The sign could have some unintended consequences. Evangelicalism is exhibiting signs of broad differences of opinion in the area of worship. As one segment goes further into minimizing worship styles to appeal to a wider unchurched public another segment seeks to retain or heighten the liturgy that has been a part of the church for over a millennia.