After heightened interest following the centennial of Charles Darwin’s Origin of Species and publication of the American Scientific Affiliation’s Evolution and Christian Thought Today, edited by Russell Mixter, on February 16, 1961 Wheaton hosted a science symposium, titled Origins and Christian Thought, that eventually stirred up significant controversy for the college. Attendees from the community, particularly a local pastor, spread word that Wheaton was “countenancing evolution and theistic evolution.” Once this was published in conservative journals president V. Raymond Edman received a deluge of concerned mail. Each letter was answered with several documents being sent as enclosures. All this led to a footnote being added to Wheaton’s Statement of Faith that read: “Wheaton College is committed to the Biblical teaching that man was created by a direct act of God and not from previously existing forms of life; and that all men are descended from the historical Adam and Eve, first parents of the entire human race.”

After heightened interest following the centennial of Charles Darwin’s Origin of Species and publication of the American Scientific Affiliation’s Evolution and Christian Thought Today, edited by Russell Mixter, on February 16, 1961 Wheaton hosted a science symposium, titled Origins and Christian Thought, that eventually stirred up significant controversy for the college. Attendees from the community, particularly a local pastor, spread word that Wheaton was “countenancing evolution and theistic evolution.” Once this was published in conservative journals president V. Raymond Edman received a deluge of concerned mail. Each letter was answered with several documents being sent as enclosures. All this led to a footnote being added to Wheaton’s Statement of Faith that read: “Wheaton College is committed to the Biblical teaching that man was created by a direct act of God and not from previously existing forms of life; and that all men are descended from the historical Adam and Eve, first parents of the entire human race.”

All posts by David Malone

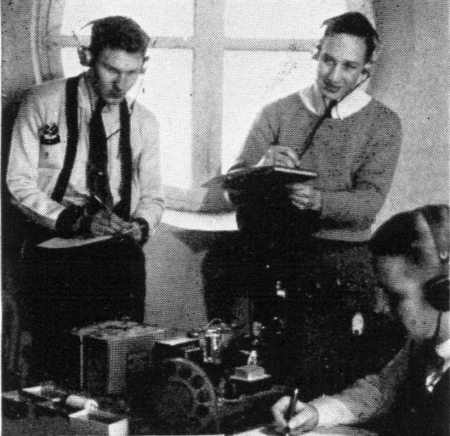

Hamming it up

In March 1937 a group of radio enthusiasts formed the Tower Radio Club. Using its own funds the club built a 1/2 kiloWatt transmitter that could reach forty states. Under the direction of physics professor Paul E. Stanley the club trained students in radio communication. The club was also able to meet some of the communication needs of the college. The club would also broadcast football games from DeKalb, as well as the North Central College basketball classic.

In March 1937 a group of radio enthusiasts formed the Tower Radio Club. Using its own funds the club built a 1/2 kiloWatt transmitter that could reach forty states. Under the direction of physics professor Paul E. Stanley the club trained students in radio communication. The club was also able to meet some of the communication needs of the college. The club would also broadcast football games from DeKalb, as well as the North Central College basketball classic.

Former member Clayton Howard ’39 used the skills he picked up in those early years as he later would serve as a technician at HCJB (Heralding Christ Jesus’ Blessings) radio station in Quito, Ecuador. He worked at HCJB for over forty years and was well known as the host of the DX Partyline show. Upon his retirement Radio Moscow broadcast “The living legend of the Andes has retired!” The club continued on for several more decades after Howard’s time.

But when Rich Boyd ’74 arrived at Wheaton College in 1970 he was an DXer (distancer) and wanted to join up with Wheaton’s club ham station, because, as he saw it, every college certainly must have one. He asked around and had no success in making contact. Until, that is, when he spotted the radio antennae perched atop Blanchard Tower. Tracing the cable from the “tribander” he saw them loop into a window in the tower. Some snooping and detective work helped him locate the hamshack on the fourth floor tower room (renamed the Arthur Holmes Seminar room after the 1990 remodeling).

Once he made his way inside Boyd found a copy of the club’s ham license and found that the station hadn’t been used since the fifties. The radio gear was in mint condition underneath the dusty tarps. Boyd soon got the club back up and running with a dozen or so other guys.

Just as the radio club continued on for several decades after Clayton Howard’s years, so too did the club go on after Boyd’s time. The Tower Radio Club was operating in the early 1990s when the Internet was mainly for academic use and the World Wide Web was yet the rage. However, today, in the 2010s ham radio operation may be less visible to the average person, but its usefulness is significant, particularly during times of natural disaster as was seen during Hurricane Katrina.

Our Survival in the Nuclear Age – Robert McNamara

February 4 marks the anniversary of the first U.S. helicopter being shot down over Viet Nam in 1962, just two months after helicopters arriving in Viet Nam to provide assistance to the South Vietnamese troops. There are few names associated with the entry into and the escalation of U.S. involvement in Viet Nam than Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara. He had overseen the growth of U.S. military non-combatant “advisers” from 900 to 16,00. There were well over one-half million troops in Viet Nam by the middle of 1968. McNamara’s legacy is tied to the Viet Nam era and the military strategies employed. Despite the negative assocations his defense expertise and intellect were still sought after. On February 4, 1988 McNamara delivered the the annual Tiffany Lecture on Foreign Affairs at Wheaton College. Mr. McNamara spoke on “Our Survival in the Nuclear Age.”

February 4 marks the anniversary of the first U.S. helicopter being shot down over Viet Nam in 1962, just two months after helicopters arriving in Viet Nam to provide assistance to the South Vietnamese troops. There are few names associated with the entry into and the escalation of U.S. involvement in Viet Nam than Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara. He had overseen the growth of U.S. military non-combatant “advisers” from 900 to 16,00. There were well over one-half million troops in Viet Nam by the middle of 1968. McNamara’s legacy is tied to the Viet Nam era and the military strategies employed. Despite the negative assocations his defense expertise and intellect were still sought after. On February 4, 1988 McNamara delivered the the annual Tiffany Lecture on Foreign Affairs at Wheaton College. Mr. McNamara spoke on “Our Survival in the Nuclear Age.”

The Tiffany Memorial Lecture on Foreign Affairs aims to foster interest in and understanding of international affairs at Wheaton. The Tiffany fund was established to honor the memory of Orin Tiffany, a long-time Wheaton history professor who had a passion for foreign affairs. Prof. Tiffany had the honor of attending the 1945 San Francisco Conference that established the United Nations. Past speakers include Zbigniew Brzezinski, Mark Hatfield, John Lewis Gaddis, Robert Pastor, Anthony Lake, Robert Seiple, and James Turner Johnson.

“Where the Law of God is the Law of the Land…”

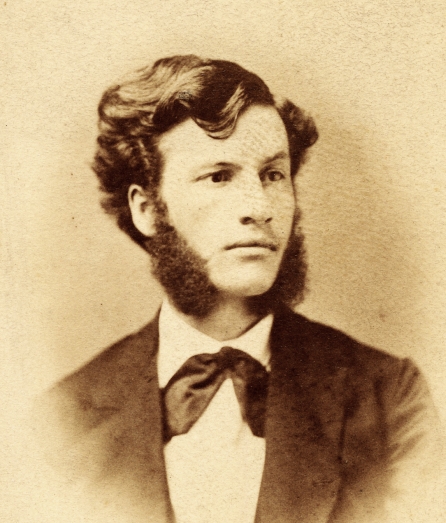

January 19 is the birthday of Jonathan Blanchard and 2011 marks the bicentennial of his birth. Blanchard had several careers of significance prior to his coming to the dreary open prairies of Wheaton Illinois in the late 1850s. He had taken great risks as one of “The Seventy” disciples of abolitionism. He was a very successful pastor in Cincinnati. He was active in getting the Liberty Party in Ohio off the ground and was friend of future members of Congress and the U. S. Supreme Court, even serving to introduce the two. He was offered a professorship of the fledgling Oberlin College and the presidency of a vibrant activist mission institute. In addition he represented his nation at the second World’s Anti-Slavery Convention in London and served as one of its vice-presidents. He also publicly debated the sinfulness of slavery with a fellow minister over four days for hours each day (these were later published and can easily be found in bookshops and libraries worldwide). He also debated Stephen Douglass. Finally, before his trek from the prosperous Galesburg to Wheaton, Jonathan Blanchard served as the second president of Knox College. His able skills brought the school recognition and solid finances.

January 19 is the birthday of Jonathan Blanchard and 2011 marks the bicentennial of his birth. Blanchard had several careers of significance prior to his coming to the dreary open prairies of Wheaton Illinois in the late 1850s. He had taken great risks as one of “The Seventy” disciples of abolitionism. He was a very successful pastor in Cincinnati. He was active in getting the Liberty Party in Ohio off the ground and was friend of future members of Congress and the U. S. Supreme Court, even serving to introduce the two. He was offered a professorship of the fledgling Oberlin College and the presidency of a vibrant activist mission institute. In addition he represented his nation at the second World’s Anti-Slavery Convention in London and served as one of its vice-presidents. He also publicly debated the sinfulness of slavery with a fellow minister over four days for hours each day (these were later published and can easily be found in bookshops and libraries worldwide). He also debated Stephen Douglass. Finally, before his trek from the prosperous Galesburg to Wheaton, Jonathan Blanchard served as the second president of Knox College. His able skills brought the school recognition and solid finances.

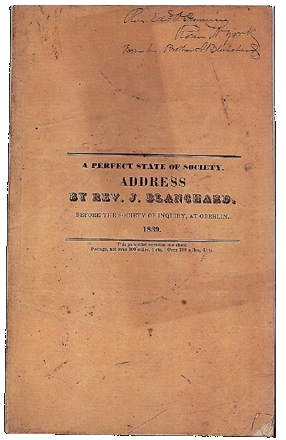

In this midst of this great career was an address that Jonathan Blanchard gave to the Society of Inquiry at Oberlin College in 1839. It was this address, A Perfect State of Society, that Jonathan Blanchard detailed his hopes and aspirations for a nation. It was these ideals that shaped his life and career as he sought to ameliorate the ills of society to usher in a state of society that would be ready for the reign of Jesus Christ. It was not that the world and society would have reached sinlessness but that things were in such order, where what needed restraint was restrained, that there was harmony. Like children need discipline, so too elements of society needed structure and restraint.

In this midst of this great career was an address that Jonathan Blanchard gave to the Society of Inquiry at Oberlin College in 1839. It was this address, A Perfect State of Society, that Jonathan Blanchard detailed his hopes and aspirations for a nation. It was these ideals that shaped his life and career as he sought to ameliorate the ills of society to usher in a state of society that would be ready for the reign of Jesus Christ. It was not that the world and society would have reached sinlessness but that things were in such order, where what needed restraint was restrained, that there was harmony. Like children need discipline, so too elements of society needed structure and restraint.

In The Perfect State of Society Blanchard sought to:

- Specify some things which we are not to expect; — and

- Some things we ARE to look for in a Perfect State of Society.

- Suggest some of the ways and means by which this desired condition of things is to come.

Blanchard didn’t want his listeners, and later his readers, to misunderstand. This perfect state of society was not a return to Edenic glory. It was a place where the Gospel had done for all what it could do for one. The Gospel’s function was to restore and reclaim. This society would “take up sinful mortals and fit them for heaven.” “Society is perfect where what is right in theory exists in fact; where practice coincides with principle and the law of God is the law of the land.”

If one wants to understand the life and mind of Jonathan Blanchard, particularly on this bicentennial, then one must understand and engage A Perfect State of Society. This address will not only help you understand this forgotten figure of 19th-century American history, but it will help you understand the time in which he lived–a time filled with Utopian ideals.

– Download A Perfect State of Society, 1839 (17 pages)

What a character…

In 1953 William Akin, generous rare book donor to Wheaton College, recounted in a Union League Club publication that while working for the Chicago Daily News he found himself in San Antonio, Texas and had a chance meeting with, what he called, using as he described it, the radio-parlance of the day, “a character.”

As he was making his way to his room in the Plaza Hotel he passed a room from which emanated singing accompanied by some guitar music. To Akin the music sound quite familiar so he knocked on the door. Being invited in Akin found Carl Sandburg sitting on the bed, in a crouching position with his shoes off. There Sandburg, who Akin always found to be unusual and unorthodox, was playing the guitar and singing to himself. Akin enjoyed the company and music for over an hour.

As he was making his way to his room in the Plaza Hotel he passed a room from which emanated singing accompanied by some guitar music. To Akin the music sound quite familiar so he knocked on the door. Being invited in Akin found Carl Sandburg sitting on the bed, in a crouching position with his shoes off. There Sandburg, who Akin always found to be unusual and unorthodox, was playing the guitar and singing to himself. Akin enjoyed the company and music for over an hour.

Sandburg was an avid guitar player and had the chance to meet Andres Segovia in 1938. Sanburg had followed Segovia since hearing his recordings twenty years earlier. The meeting with the father of modern classical guitar helped to reinvigorate Sandburg and his writing.

One can now purchase recordings, once long-unavailable, of Sandburg singing folk songs like “Cigarettes Will Spoil Yer Life” and “We’ll Roll Back The Prices.”

We never have worked pleasantly together….

In late June 1871, the twenty-two year old Charles Blanchard wrote to his mother about his travels from Worcester, Massachusetts to Bailey Hollow, Pennsylvania. Following his graduation from Wheaton College in 1870 Charles lectured on behalf of the National Christian Association, a reform organization dedicated chiefly to opposing Freemasonry and other oath bound orders. By the time he graduated from Wheaton College in 1870, he had presented 65 addresses concerning the ills of lodgery.

In late June 1871, the twenty-two year old Charles Blanchard wrote to his mother about his travels from Worcester, Massachusetts to Bailey Hollow, Pennsylvania. Following his graduation from Wheaton College in 1870 Charles lectured on behalf of the National Christian Association, a reform organization dedicated chiefly to opposing Freemasonry and other oath bound orders. By the time he graduated from Wheaton College in 1870, he had presented 65 addresses concerning the ills of lodgery.

Among other topics, Charles references Asa Packer and the founding and operation of Lehigh University. He also writes of his uncertainty for his future as he considered law, ministry or taking a stab at newspapers. It is obvious that this had been a topic of conversation of Charles with his parents.

Knowing that his father, Jonathan, had bouts of illness and poor health Charles feared that if his father’s health were to fail terribly that the college would become a “timeserving nerveless thing.” Likely reflecting hiss own concern Jonathan urged Charles to begin working at Wheaton. Despite his father’s desires and his own aimlessness, Charles tells his mother that his father and he have “never have worked pleasantly together and can do nothing in such a work unless we did.” Charles obviously had struggled with his father and wrote of Jonathan, he “will stand for his convictions as no other man I know.” Charles eventually came to terms with his father and his headstrong personality. In 1872, Charles began the affiliation with Wheaton College which was to last the rest of his life. That year he took the position of Principal of the Preparatory Department.

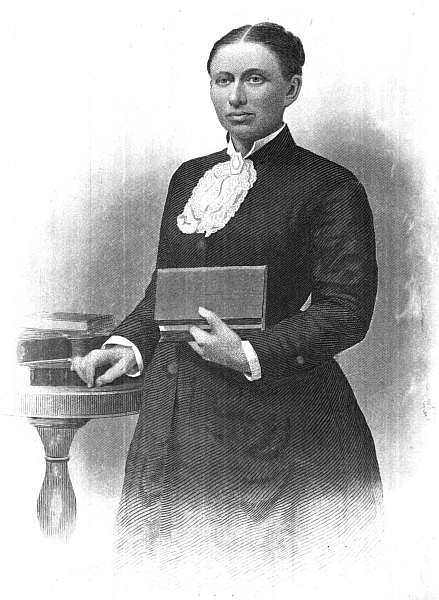

Jennie Smith, railroad evangelist

In the correspondence in the Charles A. Blanchard papers there is an 1883 Christmas Eve letter from Ellen Milligan Blanchard, Charles’ first wife, to her mother-in-law, Mary Bent Blanchard. In it Ellen writes that Charles had brought Jennie Smith, evangelist of the Railroad men to visit and speak in the college chapel. As noted in a prior blog entry, it was rather unusual for women to be involved in direct public ministry, particularly as pastors or evangelists. Charles Blanchard clearly resisted this trend and endorsed the ministry of numerous women in ministry.

The life and ministry of Jennie Smith is revealed well within the holdings of the Evangelism and Missions Collection. In 1876 Smith wrote Valley of Baca, wherein she recorded her birth, youth, sufferings and triumphs. Smith was the first child born to James and Eliza Smith on August 18, 1842 in Vienna, Ohio, west of Warren and north of Youngstown, a few miles from the Pennsylvania border. Smith came to faith as a child through Christian literature, coupled with the death of a brother and local Sabbath schools. According to her memory her childhood was one of plenty–a situation that changed after her father’s passing.  It was prior to this loss that Smith succumbed to typhoid fever that resulted in a spinal disease. Her illness resulted in isolation and a broken engagement. Though she would regain her strength and health from this bout a deeper illness and fever fell upon Smith in early 1862, resulting in a paralysis. An inventor created a portable cot for Smith so that she could travel. In illness or health Smith took advantage of opportunities to speak about God’s mercies to her doctors and visitors. In her first memoir she noted that Christian people were not as charitable to “railroad hands, street-car drivers and conductors, livery men, firemen, policemen and others, including domestic servants” who often, due to work schedules, lack the liberty to attend worship services. Smith was keenly aware that her illness put great strains on her family and others.

It was prior to this loss that Smith succumbed to typhoid fever that resulted in a spinal disease. Her illness resulted in isolation and a broken engagement. Though she would regain her strength and health from this bout a deeper illness and fever fell upon Smith in early 1862, resulting in a paralysis. An inventor created a portable cot for Smith so that she could travel. In illness or health Smith took advantage of opportunities to speak about God’s mercies to her doctors and visitors. In her first memoir she noted that Christian people were not as charitable to “railroad hands, street-car drivers and conductors, livery men, firemen, policemen and others, including domestic servants” who often, due to work schedules, lack the liberty to attend worship services. Smith was keenly aware that her illness put great strains on her family and others.

In 1880 Smith published From Baca to Beulah as she continued to tell the story of God’s work in her life. She recounted how in 1877 she felt the call as an Evangelist while speaking to a Friends (Quaker) group in Woodbury, Ohio. This spurred Smith on to ministry and began her travels–all in her portable cot. During her work she would seek medical attention as needed and consult with panels of physicians seeking restoration. In late March 1878 Smith sensed a strengthening of her faith and asked her physician to pray with her for God’s help. Smith recounted that it was during this prayer that she felt “the instant cessation of all pain.” She exclaimed how she “praised the Lord many times for a praying physician.” In less than a month Smith was able to stand and walk.  She welcomed the opportunity to sit to dinner with family, something she had not done “since February 23, 1862.”

She welcomed the opportunity to sit to dinner with family, something she had not done “since February 23, 1862.”

During her time bed-bound Smith and her family relied upon the generosity of others. In those days there was no large governmental or private social service structure that serves so many today. Smith noted that the only funds she had was in her “bank of trust” in her heavenly Father.

As noted above, Jennie Smith was known for her work with “Railroad men.” She was drawn to working with these workers when she was paralized and had relied on rail staff to carry her helpless body when she traveled by train, in the baggage cars, for treatment. Smith was struck by their noble and generous work, yet they were often spiritually neglected. After her healing she chose as her work to minister among “railroad people” and was made the National Superintendent of the Railroad Department of the Woman’s Christian Temperance Union. So touched were the workers on the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad by Smith’s tireless ministry and efforts to obtain for them a “mansion in the skies” that they sought to raise funds sufficient to purchase her an earthly home. This fund drive was limited to B&O Railroad employees and was not to exceed $1 per person.

Smith felt her particular mission was to travel on the railroads and give meetings and her testimony along the routes. She took efforts to inform others of her work and along with the two volumes mentioned above she went on to write books Ramblings in Beulah Land, volumes 1 and 2, published in 1881 and 1882 and Incidents and Experiences of a Railroad Evangelist (1920). Despite so many years physically impaired Smith continued her ministry for many years until her death on September 3, 1924 at the age of 82.

Gospel Pearls

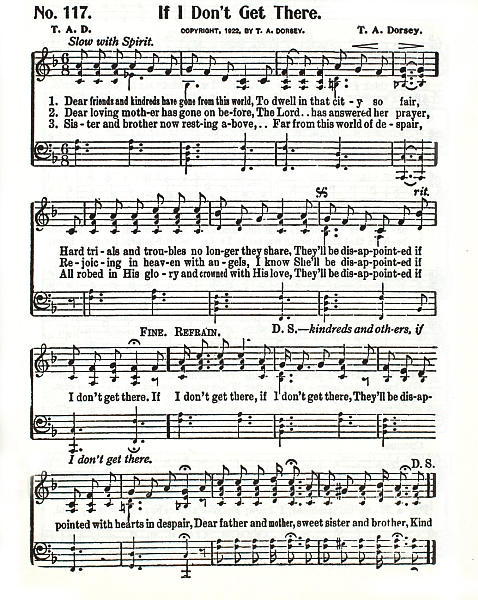

Two hundred and ten years ago African Methodist Episcopal Church founder Richard Allen published A Collection of Spiritual Songs and Hymns, selected from various authors. The first hymnal published with the intent to serve the black church, Allen sought to divert black worshipers away from the official Methodist hymnal. Within the first year a second edition was published. The hymnal, pocket-sized at 3″ x 5″, was known to be popular, however few copies are known to exist and only microfilm editions are listed in OCLC’s Worldcat. One reason this seminal hymnal is so important is that it reflected the songs that black Christians in America enjoyed singing and that were popular. Allen’s hymnal is the precursor of the gospel hymnal of nearly a century later.

One hundred and twenty years after Allen’s hymnal made it into the hands of worshipers Gospel Pearls was published. Despite the large numbers of gospel hymnals in the marketplace and in churches, the publishers of Gospel Pearls, the National Baptist Convention Sunday School Publishing Board, made no apology for its availability citing the “present day needs of the Sunday school, Church, Conventions and other religious gatherings” since its songs were “suitable for Worship and Devotion, Evangelistic Services, Funeral, Patriotic and other special occasions.”

One hundred and twenty years after Allen’s hymnal made it into the hands of worshipers Gospel Pearls was published. Despite the large numbers of gospel hymnals in the marketplace and in churches, the publishers of Gospel Pearls, the National Baptist Convention Sunday School Publishing Board, made no apology for its availability citing the “present day needs of the Sunday school, Church, Conventions and other religious gatherings” since its songs were “suitable for Worship and Devotion, Evangelistic Services, Funeral, Patriotic and other special occasions.”

This hymnal, found in the Special Collection’s Hymnal Collection (SC 15-1208), was created under the direction of Willa Townsend and contained 164 songs, including works by white gospellers like Sankey, Bradbury, Bliss, Crosby and Rodeheaver, but also works by black writers like Charles Tindley, Lucie Campbell, and, notably, Thomas A. Dorsey. Townsend included one of her own works in Gospel Pearls, “Wade in the Water.”

Tindley is recognized as one of the founding fathers of American gospel music, but it was Dorsey who would have the biggest impact on this musical form.  Songs written in Dorsey’s musical style were called “dorseys” and were a combination of Christian praise and rhythm and blues and jazz music stylings. Incorporating much of late-nineteenth and early-twentieth century hymnody’s emphasis upon personal experience, Dorsey’s gospel songs influenced mainstream white music, both secular and sacred. Gospel Pearls included Dorsey’s “If I Don’t Get There,” but he was famous for his song “Precious Lord, Take My Hand.” So beloved was this song that it was recorded by a wide range of singers, both black and white, like Albertina Walker, Elvis Presley, Mahalia Jackson, Aretha Franklin, Jim Reeves, Roy Rogers, and Tennessee Ernie Ford and many many more. It was also the requested song for the funerals of Martin Luther King, Jr. and Lyndon B. Johnson.

Songs written in Dorsey’s musical style were called “dorseys” and were a combination of Christian praise and rhythm and blues and jazz music stylings. Incorporating much of late-nineteenth and early-twentieth century hymnody’s emphasis upon personal experience, Dorsey’s gospel songs influenced mainstream white music, both secular and sacred. Gospel Pearls included Dorsey’s “If I Don’t Get There,” but he was famous for his song “Precious Lord, Take My Hand.” So beloved was this song that it was recorded by a wide range of singers, both black and white, like Albertina Walker, Elvis Presley, Mahalia Jackson, Aretha Franklin, Jim Reeves, Roy Rogers, and Tennessee Ernie Ford and many many more. It was also the requested song for the funerals of Martin Luther King, Jr. and Lyndon B. Johnson.

Give me the harp I hear…

Shortly after the death of seven-month old Jonathan Edwards Blanchard in Cincinnati another child was conceived by Jonathan and Mary Blanchard. Born on January 7, 1841, Mary Avery Blanchard entered life on her mother’s birthday and was so named for her. The eldest of the Blanchard children, Jonathan and Mary sought to provide the best educational opportunities for Mary Avery. For a summer she lived with the John Payson Willistons and enrolled in school in Northampton, Massachusetts. While in school Jonathan wrote his daughter encouraging her to not worry about her grade level but whether she was thorough in her work. When she wrote back in one letter about the handsome men Jonathan wrote back and said she was there to study. Displaying his beliefs about the education of women Jonathan had Mary Avery studying Greek, so that she may read the New Testament, Latin and Mathematics. He told her that “Latin was a glorious language of a glorious people….Love it.” When Mary Avery returned to Galesburg she finished her studies at Knox Female Seminary and became a school teacher in Prospect City, Illinois for a time. When she was seventeen she enrolled at Mount Holyoke College. Jonathan expected much of his eldest child. She had the same impetuous spirit as her father. Engaged for a time to a Mr. Caldwell, someone that Jonathan believed to be less than pious, Mary Avery snapped back that she would marry him and they would go to hell together. However, before they could wed Mary Avery contracted consumption, known today as tuberculosis. Though she was able to make the move to Wheaton with the family when Jonathan assumed the presidency of Wheaton College, Mary Avery died on December 6, 1860, a month before her twentieth birthday. This was the fourth child that Jonathan and Mary Blanchard had lost before reaching full adulthood. Enamored with the work of John G. Fee, Mary Avery bequeathed what little worldly goods she had to his work at Berea College in Kentucky.

Shortly after the death of seven-month old Jonathan Edwards Blanchard in Cincinnati another child was conceived by Jonathan and Mary Blanchard. Born on January 7, 1841, Mary Avery Blanchard entered life on her mother’s birthday and was so named for her. The eldest of the Blanchard children, Jonathan and Mary sought to provide the best educational opportunities for Mary Avery. For a summer she lived with the John Payson Willistons and enrolled in school in Northampton, Massachusetts. While in school Jonathan wrote his daughter encouraging her to not worry about her grade level but whether she was thorough in her work. When she wrote back in one letter about the handsome men Jonathan wrote back and said she was there to study. Displaying his beliefs about the education of women Jonathan had Mary Avery studying Greek, so that she may read the New Testament, Latin and Mathematics. He told her that “Latin was a glorious language of a glorious people….Love it.” When Mary Avery returned to Galesburg she finished her studies at Knox Female Seminary and became a school teacher in Prospect City, Illinois for a time. When she was seventeen she enrolled at Mount Holyoke College. Jonathan expected much of his eldest child. She had the same impetuous spirit as her father. Engaged for a time to a Mr. Caldwell, someone that Jonathan believed to be less than pious, Mary Avery snapped back that she would marry him and they would go to hell together. However, before they could wed Mary Avery contracted consumption, known today as tuberculosis. Though she was able to make the move to Wheaton with the family when Jonathan assumed the presidency of Wheaton College, Mary Avery died on December 6, 1860, a month before her twentieth birthday. This was the fourth child that Jonathan and Mary Blanchard had lost before reaching full adulthood. Enamored with the work of John G. Fee, Mary Avery bequeathed what little worldly goods she had to his work at Berea College in Kentucky.

Upon Mary Avery’s death M. F. Bigney, editor of the the New Orleans paper, The Daily City Item, wrote

Give Me The Harp. She was known as a pious girl and these words were based upon her final earthly words, “Give me the harp I hear.” The poem appeared in Bigney’s The Forest Pilgrims, and other poems published in 1867.

Give me the harp with the sounding strings,

The harp whose tones I hear–

It seems upborne by an angel’s wings,

And unto my bursting heart it brings

The sounds of hope and cheer–

A melody all divine, that springs

From a higher and purer sphere.

Give me the harp, and this trembling hand

Released from the ills of earth,

Shall learn the lays of the better land,

Shall touch the strings with a high command,

And the joy of a spirit-birth

Shall thrill my soul with a rapture grand,

With a fond and holy mirth.

Give me the harp, and I’ll bid farewell

To the fleeting scenes of time ;

With the loved ones gone before I’d dwell,

My harp with theirs should the echoes swell

Of a high immortal rhyme ;

Give me the harp, for I fain would tell

Of release from this world of crime.

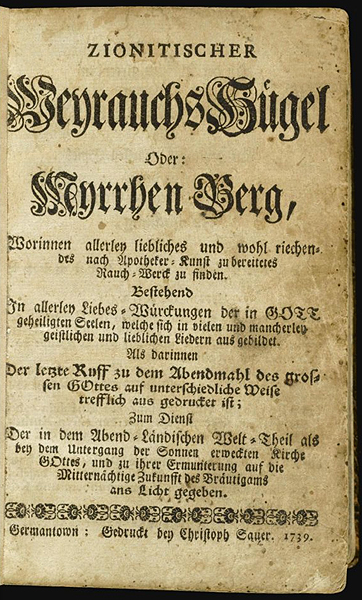

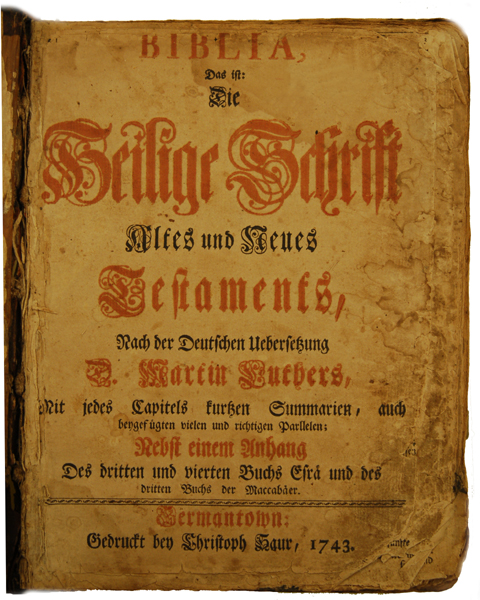

“For the glory of God and my neighbor’s good”

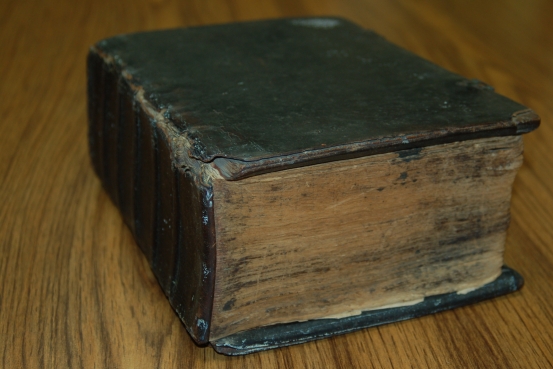

One would think that Wheaton College would have one of the best bible collections around–at least among small colleges. Unfortunately, this is not the case. However, over time and through purchasing and gifts it is possible for Wheaton expand its current holdings. One way in which the Archives & Special Collections has expanded its holding is through the acquisition of several collections that had been a part of the holdings of the Billy Graham Center Museum and Library. One such gem that came via the museum was a copy the first bible printed in America in an European language (German). A later edition of this bible became known as the “gun-wad bible” because during the Battle of Germantown (1777) during the American Revolution British soldiers broke into the printer’s shop and confiscated thousands of pages of the yet completed bibles and used them for gun-wadding.

Christopher Sauer, born Johann Christoph Sauer in 1695, sailed to America with his wife and young son in 1724 and nearly fifteen years later had established a thriving printing business. Historians have recognized Christopher Sauer (also known to history as Johann Christoph Sauer, Christoph Saur, Christoph Sauer and Christopher Sower) as one of the most important figures of colonial Pennsylvania. Sauer was known as a separatist and did not seem to be a part of any particular religious community, though his wife had moved to the Ephrata commune near Germantown, leaving the senior and junior Christoph.

In 1743 Saur printed the first European-language Bible printed in America. The only bible printed in America prior to this was John Eliot’s Algonquin Bible (1663). Sauer’s bible was a huge undertaking and became a 1267 page volume. This is considered one of the largest printing ventures in America at the time. Eventually the 1200 copies printed were sold. Though he was a business man he made it known that those who were poor and could not afford his bible could ask to receive one. Sauer’s son eventually printed a second edition in 1763 and a third in 1776 (mentioned above) — all before Robert Aitken’s “Congress Bible” of 1782.

As would reflect the future nature of American religion, Sauer’s bible created controversy and division even before it was finished. Area Lutheran and Reformed clergy feared the translation chosen, Berleberg’s, along with some of the printing’s typographical errors would confusion readers and encourage heresy. Sauer did not help his situation by using multiple translations in a single book (Job). Despite the pressure Sauer pressed on.

To date about two hundred of Sauer’s publications have been identified. His press, which he built himself, was quite active and produced a steady stream of devotional and theological works. Some of the earliest hymnals for German speakers came from Sauer’s press. In fact the first publication off of his press was a hymnal that was reprinted over and over again. The type was sent to him from Germany by Christopher Shutz. Sauer was well-acquainted with revivalist George Whitefield and had hopes of printing devotional and theological works in English, including a quarto-sized bible, but the high cost of paper proved a hurdle too great.

To date about two hundred of Sauer’s publications have been identified. His press, which he built himself, was quite active and produced a steady stream of devotional and theological works. Some of the earliest hymnals for German speakers came from Sauer’s press. In fact the first publication off of his press was a hymnal that was reprinted over and over again. The type was sent to him from Germany by Christopher Shutz. Sauer was well-acquainted with revivalist George Whitefield and had hopes of printing devotional and theological works in English, including a quarto-sized bible, but the high cost of paper proved a hurdle too great.

His motto for his press was “For the glory of God and my neighbor’s good.” Sauer wrote to a patron in September, 1740, that “I would rather serve my neighbor and glorify God in that way than to gather a large earthly fortune for myself or for my son….” He continued, saying, “that nothing shall be printed except that which is to the glory of God and for the physical or eternal good of my neighbors. What ever does not meet this standard, I will not print. I have already rejected several, and would rather have the press standing idle. I am happier when I can distribute something of value among the people for a small price, than if I had a large profit without a good conscience.” He was known for his charitable works, so much so that he was known as “Bread Father” and the “Good Samaritan” of Germantown. It is said that he would meet German immigrants as they arrived on ships provide hospitality to the sick and needy.

Sauer did what he could to expand his work and to make his publications affordable. He had heard of a printer in Philadelphia that claimed knowing the formula for a better ink and Sauer inquired about learning the formula. Asking what the printer would ask in return for teaching Sauer the printer asked Sauer to build him a press like his own. Saying he would consider the trade Sauer later thought to myself, “You have carried on twenty-six trades and crafts without any teacher, and made almost all of the tools necessary for them. Why should you now pay so dearly for this knowledge?” The next morning he had an idea on how to make the a new ink. The ink was as good and even cheaper than the old.

Sauer did what he could to expand his work and to make his publications affordable. He had heard of a printer in Philadelphia that claimed knowing the formula for a better ink and Sauer inquired about learning the formula. Asking what the printer would ask in return for teaching Sauer the printer asked Sauer to build him a press like his own. Saying he would consider the trade Sauer later thought to myself, “You have carried on twenty-six trades and crafts without any teacher, and made almost all of the tools necessary for them. Why should you now pay so dearly for this knowledge?” The next morning he had an idea on how to make the a new ink. The ink was as good and even cheaper than the old.

Christopher Sauer died on September 25, 1758, after a remarkable career in America. During his thirty-four years in America his press operation and intellectual interests put him at the forefront of many of the important controversial political and theological issues of his day. About one fifth of the publications of his press were translations or reprints of European books, largely theological or devotional in nature. These productions helped to maintain America’s European ties. Conversely, many of Sauer’s American works were reprinted in Europe, bringing ideas from the New World to the Old.

This entry in indebted to Donald Durnbaugh’s wonderful article on Sauer.

[Durnbaugh, Donald F. “Christopher Sauer Pennsylvania-German Printer: His Youth in Germany and Later Relationships with Europe.” The Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography, Vol. 82, No. 3 (Jul., 1958), pp. 316-340.]