In a November 1892 edition of the Wheaton College Record Charles Blanchard, serving as editor, noted three of Wheaton’s “daughters true” who were ordained ministers in their respective denominations. In what would seem as an interesting “reversal” for many today, it was not out of place for these alumnae of Wheaton College to be active leaders in the church. He spoke of these women in glowing terms in a way that clearly confirmed their gifts and calling.

The first ordination of a Northern Baptist (now known as the American Baptist Churches, USA) occurred in 1882. May C. Jones was ordained at a meeting of the Baptist Association of Puget Sound in Washington. Women were generally discouraged from entering the ministry in this denomination. In 1885 Frances E. “Fannie” Townsley became the second-known Baptist woman ordained. Townsley had begun preaching in churches and holding evangelistic services throughout New England in 1875. She was licensed to preach by her church in Shelburne Falls, Massachusetts and several years later moved to Fairfield, Nebraska. There she pastored Fairfield Baptist Church. After serving successfully as an evangelist for twelve years Townsley still lacked ordination and the ability to administer sacraments. The deacons of Fairfield asked to ordain her. After resisting this move for several months Townsley consented to ordination in April 1885. Her ordination exam took three hours and covered, as well, her sense of call and doctrinal views.

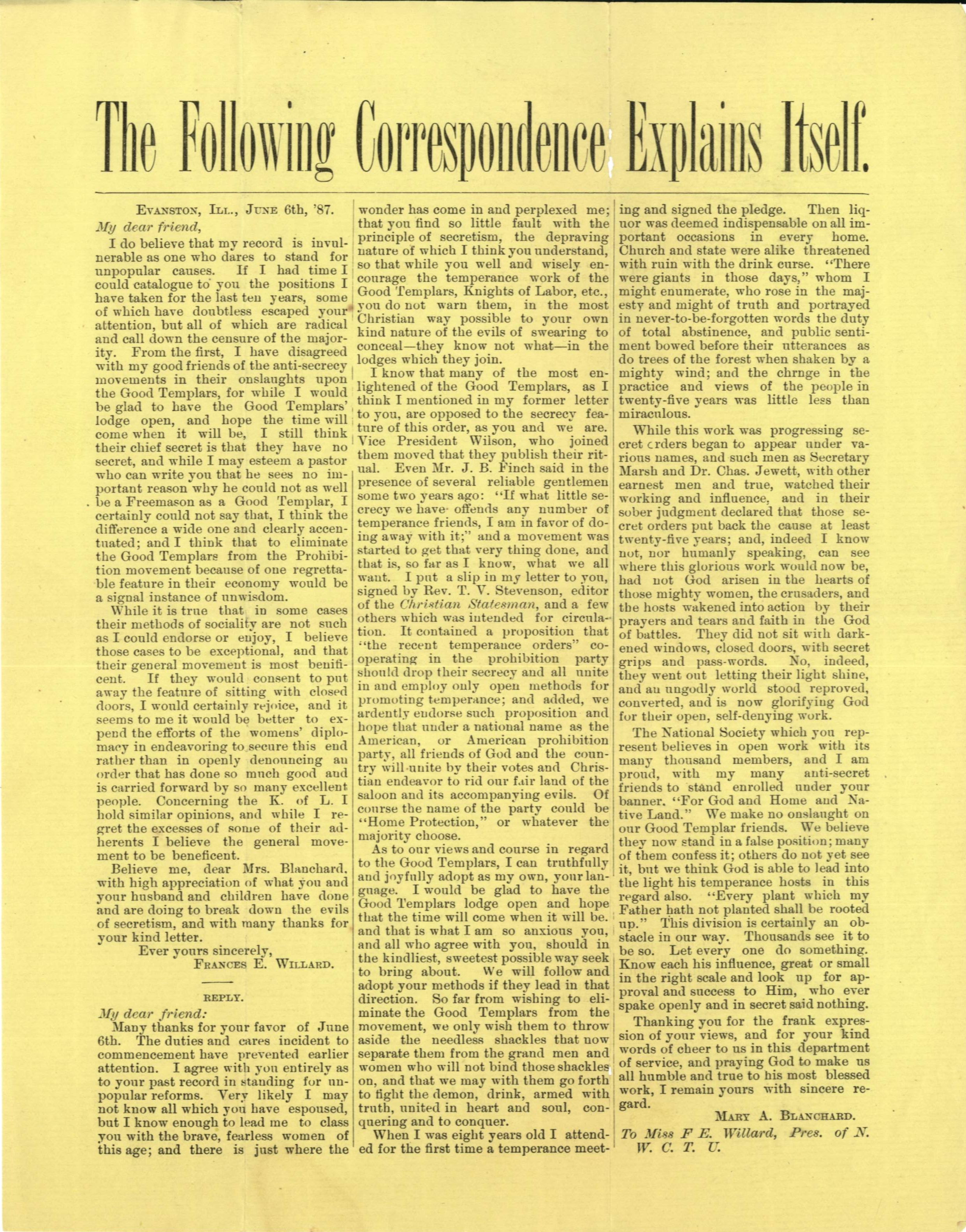

The first ordination of a Northern Baptist (now known as the American Baptist Churches, USA) occurred in 1882. May C. Jones was ordained at a meeting of the Baptist Association of Puget Sound in Washington. Women were generally discouraged from entering the ministry in this denomination. In 1885 Frances E. “Fannie” Townsley became the second-known Baptist woman ordained. Townsley had begun preaching in churches and holding evangelistic services throughout New England in 1875. She was licensed to preach by her church in Shelburne Falls, Massachusetts and several years later moved to Fairfield, Nebraska. There she pastored Fairfield Baptist Church. After serving successfully as an evangelist for twelve years Townsley still lacked ordination and the ability to administer sacraments. The deacons of Fairfield asked to ordain her. After resisting this move for several months Townsley consented to ordination in April 1885. Her ordination exam took three hours and covered, as well, her sense of call and doctrinal views.  As one might expect for the times, Townsley endured criticism and resistance after her ordination. She would later travel frequently to preach in towns throughout Nebraska, and served as a temperance leader. She supplied three pastorates in Nebraska then resumed evangelistic work. She filled a number of Baptist pulpits for months. Her last charge was the Covenant of Chicago. Years later, around the turn of the century Townsley, living in Maywood, Illinois, had an award-winning essay published by the Women’s National Sabbath Alliance. Townsley also served as an editor for The Union Signal, the official paper of the Women’s Christian Temperance Union.

As one might expect for the times, Townsley endured criticism and resistance after her ordination. She would later travel frequently to preach in towns throughout Nebraska, and served as a temperance leader. She supplied three pastorates in Nebraska then resumed evangelistic work. She filled a number of Baptist pulpits for months. Her last charge was the Covenant of Chicago. Years later, around the turn of the century Townsley, living in Maywood, Illinois, had an award-winning essay published by the Women’s National Sabbath Alliance. Townsley also served as an editor for The Union Signal, the official paper of the Women’s Christian Temperance Union.

Jennie Hewes Caldwell served, with great success, as an evangelist among the Methodist churches of the United States and Great Britain. She was, at one time, a teacher at Wheaton College and was remembered for her care and concern for her students.

Miss Juanita Breckenridge was the ordained pastor of the Brooktondale Congregational church in Brooktondale. N. Y. and the first female Bachelor’s of Divinity graduate from Oberlin Seminary–the Bachelor’s of Divinity is the equivalent of today’s Master’s of Divinity. Miss Breckenridge caused quite a stir as she sought a license to preach along with her fellow male students while at Oberlin. She was eventually granted the license and ordained.

Miss Juanita Breckenridge was the ordained pastor of the Brooktondale Congregational church in Brooktondale. N. Y. and the first female Bachelor’s of Divinity graduate from Oberlin Seminary–the Bachelor’s of Divinity is the equivalent of today’s Master’s of Divinity. Miss Breckenridge caused quite a stir as she sought a license to preach along with her fellow male students while at Oberlin. She was eventually granted the license and ordained.